Here's the cash buffer you need to survive

“Income volatility” and “unexpected expenses” are somewhat of an oxymoron -- they’ve become so commonplace it’s hard to consider them rare.

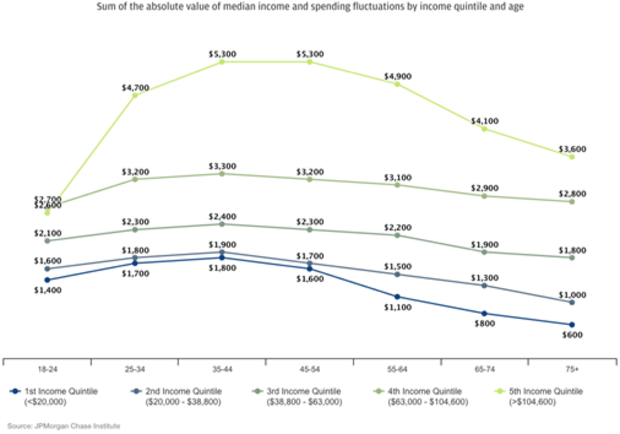

The financial ups-and-downs of American families are prompting new research into how households cope with these swings, as well as how they affect those who are unprepared to handle a sudden hit. Family income and spending fluctuate by about 30 percent from month to month, which translates into an unplanned expense of $1,300 for middle-income households, according to research from the JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Such swings can wreak havoc on family budgets, especially for those without a lot of wiggle room. Financial advisers typically recommend that Americans sock away about six months of income in case of a job loss or other emergency, but considering that most adults can’t afford a $500 emergency expense, that’s likely to be out reach for many.

A smaller cash cushion can serve as a buffer for those times when a medical bill or dip in income stresses your budget, said Diana Farrell, chief executive officer of the JPMorgan Chase Institute.

“You wouldn’t worry about it if it happened in a month where your income dips when you spend less, but they aren’t correlated,” Farrell said of income swings and expenses. “So we’re trying to understand how much cash you need in a buffer to cover that level of volatility.”

JPMorgan’s research is based on de-identified data from Chase customers, and it includes samples ranging from 100,000 to 1 million customers. The data provides insights into how consumers actually earn and spend, compared with self-reported survey data, which can be inaccurate because it’s based on memory and expectations.

The everyday cash buffer needed by families peaks between the ages of 35 to 44, when it reaches $2,400 for middle-income families.

The highest-income families -- those who earn more than $104,600 per year -- need their largest buffer when they’re between the ages of 35 to 54. At at that point, they should have $5,300 on hand to cover the typical ebbs and flows of income and expenses.

Interestingly, young workers start their careers with fairly similar needs for their cash buffers, the research found. The lowest-income workers should have $1,400 in their everyday cash buffer, compared with $2,700 for the highest-income workers in the 18 to 24 age group. But by the time workers reach old age, the dispersion is far wider.

The reason? Young workers have more similar expenses, partly because they’re relatively healthy as a group and are also finding their first jobs and apartments. Older Americans are much less alike, given a wider variety of health issues and living arrangements.

“The experience of old people is much more dispersed,” Farrell said. “You have more variety in expenses and in income than you would have in any other age group. If you think about the experiences of old age, some people live in homes with their children, some in retirement homes.”

Farrell recommends that households keep their everyday cash buffer in a savings account. She said households should still aim to have an emergency savings account of the three to six months of income recommended by financial experts. Those assets could be kept in money market funds, certificates of deposit or other vehicles that are slightly less liquid than a bank account.

What happens if a household doesn’t have the assets on hand to cover an emergency expense or income dip? It’s not always pretty, according to the bank’s data.

An emergency medical expense typically sets a household back by $2,089, and most families are still feeling the impact 12 months later, with liquid assets about 2 percent lower and credit card debt 9 percent higher.

“People scramble to pull together whatever they can, but they don’t recover for at least a year after,” Farrell said. “For those who don’t have the ability to pay, they in fact go into medical debt.”

While it may seem impossible to save even the cash buffer that JPMorgan recommends, fintech services have sprung up that aim to help consumers understand their month-to-month volatility and sock away a little extra money. Those include Earn, which is a nonprofit service for working families that provides incentives for saving $20 per month, and Meet Albert, which analyzes financial data to provide recommendations for saving money.

“Between taxes, deductions, overtime and bonuses,” said Farrell, “most people are bouncing around, but they don’t necessarily have an understanding of that.”