Here's the brutal reality of online hate

WARNING: The themes of the following story are disturbing. The language includes racial and religious slurs. We have edited some of the wording because of its ugly nature but preserved the intent to present a clear picture of attacks on real people.

Mikey Weinstein knows about online harassment. He also knows what it's like when digital threats cross into real life.

About 10 years ago, someone shattered the windows of his suburban home in New Mexico. Twice. He's found a swastika and a cross painted near the front door.

But Weinstein says the decapitated rabbits are the worst. On one occasion, somebody dropped a severed rabbit's head in his driveway. Last year, a gutted bunny appeared by his front door.

Police say they've been called to the Weinstein residence many times over the years.

Weinstein doesn't scare easily. Yet the Air Force vet and former Reagan administration attorney has hired armed bodyguards after enduring years of vicious emails, hateful social media posts and hostile phone calls related to the Military Religious Freedom Foundation, the nonprofit he founded in 2005 to protect military members regardless of their faith.

The digital assaults come through his personal Facebook page, the MRFF's website and plain old email. Almost all are filled with anti-Semitic slurs and intimidating language. Sometimes he gets threatening phone calls.

You're probably a good, decent person. Sure, you might not agree with everyone, but you wouldn't start swearing at someone or slurring his religion. And you certainly wouldn't use some of the most racially charged language in English in an email, text or tweet.

Other people do. We've cleaned up most of this email Weinstein got in December 2013, but it still gives a sense of how brutal many people are on the internet:

"Hey jewboy Mickey Whinerstein. The Air Force Base in S. Carolina should make a naitivity scene out of your dismembered f----- body parts. You stinking k--- commie athiest liberal d--- sucking Obummer loving Jesus hating f----- lawyer. Who worships satan queers and abortions and muslims sand n------ like Obummer more than your own country. TRAITOR JEW!"

Weinstein gets dozens of crude emails like this every week, according to a longtime assistant and a private security guard who have sorted through his messages for years. Both say they haven't grown immune to what they see or hear, such as an anonymous caller telling Weinstein, "We're going to slash your head off and roll it down the street like a bowling ball."

It's only getting worse.

"We are very careful with all the threats that come in," Weinstein says. "The shit we get is unbelievable."

Online abuse is as old as the internet. Being anonymous encourages people to say things they'd never say in public and push the boundaries of accepted behavior because they feel they won't be held accountable. Distance adds to the problem. It's a lot harder to pull out all the stops when you're looking someone in the eye. On the internet, you don't see your target or the emotional devastation you leave behind.

Racial minorities often get the brunt of the abuse online. Black Lives Matter activists, including DeRay McKesson, have been harassed in tweets, emails and posts. And there's enough hatred out there to ensure feminists, Jews, Muslims and the LGBTQ community are constant targets.

The internet amplifies the effect, organizing the haters into packs of digital attack dogs. Step on a cultural tripwire -- try mentioning Barack Obama, standing up for immigrants or expressing support for abortion rights -- and the intolerant assemble into swarms, creating what are known as troll storms, which zero in on individuals and upend lives.

Facebook pages and Twitter feeds dedicated to hatred spring up as fast as the social networks can stamp them out. The suspect in the May stabbing death of a black Army lieutenant in Maryland belonged to a Facebook group called "Alt-Reich: Nation," where members reportedly posted and swapped racist memes. (The page was shut down after the attack.) And the man accused of stabbing three people after a racist tirade in Oregon later in May had reportedly expressed sympathy for Nazis on his Facebook page.

One racist forum, Stormfront.org, has attracted a particularly violent membership from all over the world since it was founded in 1995. Anders Behring Breivik, the man who killed 77 people in Norway in 2011, was a member for three years and emailed a racist manifesto to other members just hours before he began his rampage, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights group. Over a five-year period ending in March 2014, Stormfront members killed almost 100 people, the SPLC says.

Stormfront didn't respond to a request for comment. Its founder, Don Black, a former Ku Klux Klan member, called the SPLC's report "ludicrous" after it was released, and said the figures were inflated.

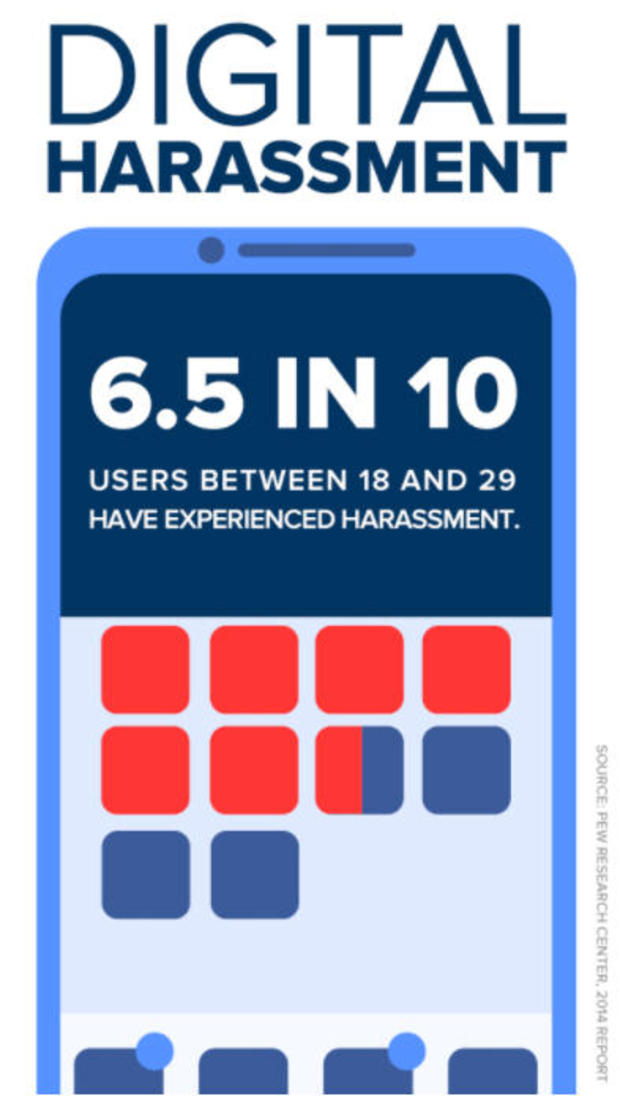

It's hard to quantify how pervasive online assaults have become, but experts say the number is growing. Four out of every 10 internet users have experienced some form of harassment, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center report. The figure leaps to 65 percent for those between the ages of 18 and 29.

The situation has gotten worse thanks to a divisive presidential campaign punctuated by race baiting, religious jabs and anti-immigration appeals.

Donald Trump's inflammatory words during the campaign -- he called Mexican immigrants "rapists" and "criminals," and at one point said, "I think Islam hates us" -- helped embolden the "alt-right," a loose movement of white nationalists and neo-Nazis who largely supported his immigration policies. Shortly after the vote, then-President-elect Trump disavowed the movement. Nevertheless, its members remain energized, particularly when the president recognizes them.

That happened over the July Fourth holiday, when President Trump tweeted a video of him tackling a wrestler whose face had been replaced with CNN's logo. The source of the video: a Reddit user with a history of posting racist and anti-Semitic comments.

The man, who was contacted by CNN, has since apologized and deleted his account. The White House didn't respond to a request for comment.

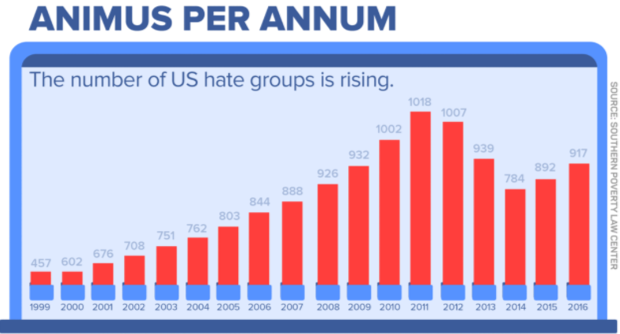

The SPLC says the number of recognized hate groups in the US began rising in 2009, when then-President Obama took office. It reached a peak of 1,018 in 2011 and then began to decline as extremists moved "to the web and away from on-the-ground activities."

Over the past few years, however, the hate group count has started rising again "in part due to a presidential campaign that flirted heavily with extremist ideas," the SPLC says. The number stands at 917 as of last year, up from 892 in 2015, with the number of anti-Muslim groups nearly tripling last year to 101.

Mark Potok, who edits the SPLC's quarterly Intelligence Report magazine, calls this the "Trump Effect." He says it's galvanized groups to use the internet to spread their messages.

"The Trump phenomena has been electrifying to the radical right wing," Potok says. "They lurk on the internet."

Weinstein agrees, saying the attacks against him and his family have gotten worse since the election.

Efforts to curb hatred online have gone nowhere. Facebook, which now has 2 billion monthly users, said last week that it deletes 66,000 hateful posts every week but acknowledged it's not yet where it needs to be. Last week, too, Germany passed a law that could bring fines as high as 50 million euros ($57 million) against social media companies if they don't block or remove hate speech within 24 hours.

Worse, people trying to stop the hatred may become targets themselves.

Massachusetts Congresswoman Katherine Clark, who's pushed the tech industry to face the problem, found that out firsthand on a cold Sunday night in January 2016.

Clark and her husband were watching "Veep" when she noticed flashing lights outside her house. Police cars had blocked off the street and armed officers faced her front door.

The representative knew immediately she was the victim of a dangerous prank known as "swatting." She was right. The police had received an anonymous report of an active shooter at her home.

Clark fell afoul of trolls because she had introduced five bills in Congress to combat online abuse. The two-term representative became involved in fighting online hate after one of her constituents, game designer Brianna Wu, became a target of rape and death threats during 2014's GamerGate controversy. That's the online campaign against activists, like Wu, who challenge the way women are portrayed in video games.

Wu told Clark she had received more than 100 death threats, prompting the congresswoman to call the FBI. She was astonished by its response. "It wasn't a priority," Clark says.

The FBI didn't respond to a request for comment.

One of the bills Clark introduced calls for $20 million in training for the Department of Justice so it can go after people violating provisions of 2013's Violence Against Women Act, which outlaws online abuse. The money would be used to teach police and prosecutors how to identify violations and collect evidence.

Clark also drafted the Interstate Swatting Hoax Act, which would make it a federal crime to falsely report an incident that leads to the dispatch of a SWAT team. Right now such incidents are covered by state laws. The bill includes provisions for life sentences in swatting incidents that result in death.

At the end of last month, Clark tweeted that she and two other members of Congress had introduced a new bill to address these and other issues, the Online Safety Modernization Act.

Targeted

In 2015, Renee Bracey Sherman co-wrote a 30-page manual on how to deal with online abuse. It wouldn't be long before the abortion-rights activist would be following her own advice.

Bracey Sherman wrote "Speak Up & Stay Safe(r)" with Anita Sarkeesian, another target of GamerGate, and Jaclyn Friedman, a feminist writer and activist. Both these co-authors had firsthand experience dealing with death threats, as did Bracey Sherman, who was the target of vicious online abuse because of a pro-choice report she wrote called "Saying Abortion Aloud."

"Speak Up" details simple ways to prevent harassment, including how to combat "doxxing," when trolls post your personal documents and information online so others can harass you. It recommends creating multiple email accounts with different, complex passwords, as well as using two-factor authentication, which requires you to pass multiple tests before getting to your account.

In December 2016, Bracey Sherman wrote an open letter to Rep. Tom Price, who was on his way to becoming President Trump's Secretary of Health and Human Services. The letter, published on Refinery 29, called on Price to keep abortion legal and safe.

Bracey Sherman recounted her own unplanned pregnancy and her decision to have an abortion. She called it "one of the best I have ever made."

It wasn't long before the trolls lashed out.

About a half-dozen right-wing blogs, including 100percentfedup.com and the now-defunct republicannation.com, picked up her letter. Soon after, derogatory posts hit her Facebook and Instagram pages as well as her email inbox.

Then her Twitter account was flooded with angry tweets calling her, among other things, "a racist bitch" and "c---." She was also ridiculed for being biracial.

She reached out to Twitter and, according to Bracey Sherman, the social network determined that about 15 percent of the tweets met its definition of a violation, so it removed those. But that only provoked the harassers, who posted new tweets, some saying "this bitch reported me to Twitter."

Twitter confirmed it worked with Bracey Sherman after she reported the harassment. The company declined to provide details, citing privacy and security concerns.

Experts say Bracey Sherman's experience is typical of the way social media magnifies hatred online by giving people who might not be affiliated with organized hate groups a sense of community.

"You don't have to be a card-carrying member of a local skinhead group or local [Ku Klux] Klan group," says Brian Levin, who runs the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. Social media, he says, has become a "force multiplier" of hatred.

As the ugly tweeting intensified, Bracey Sherman grew anxious and depressed. She stopped answering her phone and was afraid to walk down the streets of her Washington, DC, neighborhood.

The worst: the feeling that hundreds of anonymous eyes were on her at all times.

"I know they hide behind avatars [online] and they are lying in wait, and so it was that sort of a feeling, that feeling I was being stalked and they might be watching me," she says. "You never know who that person could be and where they are."

By mid-December, Bracey Sherman decided to quit social media altogether. As she left her home online, she also ditched her home in DC, leaving the capital for her parents' place in the Midwest.

"My dad picked me up from the airport, and as soon I got home, I crawled into bed with my mother and started crying," Bracey Sherman says. "It brought me back to when I was in second grade, when I stood out from my classmates because I had big curly hair, a large forehead and this dimple in my chin.

"I just really felt so defeated."

Bracey Sherman stayed off social media for six weeks until the attacks against her subsided. For inspiration, she reread the anti-online abuse guide she co-authored. She started using Block Together, an app that lets you share lists of blocked Twitter accounts with friends. She also moved into a building with around-the-clock security.

The time offline re-energized Bracey Sherman, who returned to DC just before Inauguration Day on Jan. 20. The following day, she joined hundreds of thousands at the Women's March, sporting an ironic T-shirt that said "Petty Black Feminist" and a red bomber jacket that said "Team Abortion" on the back.

Still, Bracey Sherman continues to be a target of hatred.

On June 14, a man at Reagan International Airport used Apple's AirDrop file-sharing feature to plop an image of Pepe, a cartoon frog that's been appropriated as a symbol by white supremacists, onto Bracey Sherman's Mac while she waiting for a flight. Her computer was visible because she was using Bluetooth wireless headphones and AirDrop identifies the model of a device.

"It was quite unsettling and jarring to not only see this racist meme, but it was scary that it was showing up on my computer," she said in an email. "I freaked out a little."

But not too much.

Gathering her wits, Bracey Sherman did a quick lap around the airport looking for someone on a MacBook Pro. She found him -- his name is Jacob, based on what Bracey Sherman could see on his computer -- in an airport bar.

Jacob acknowledged sending the racist meme to Bracey Sherman's computer though he wouldn't apologize. Nonetheless, she's glad she confronted him.

"Racism is real," Bracey Sherman's email read. "And this is one of the many ways it looks in the digital age."

Attack of the trolls

Norma Zahory doesn't like Trump and wanted to join the protests on Inauguration Day. But she didn't feel comfortable leaving her sick father in their suburban Maryland home.

Her absence from the protests didn't prevent the web from accusing her of assaulting a Trump supporter.

Though she was miles away from downtown Washington, people on the internet were convinced Zahory had lit a Trump supporter's hair on fire during a tense standoff on the 700 block of Pennsylvania Avenue. The incident was captured in a YouTube video that's been viewed more than 1.5 million times.

The video was immediately dissected and frames capturing a face -- one that bore a passing resemblance to Zahory's -- were passed around the web. A proposed bounty to identify the perpetrator was set up on WeSearchr, a site founded by two right-wing provocateurs that pays people to research topics. (WeSearchr said the information would be turned over to law enforcement and wasn't a call for "vigilante justice.")

"She should be arrested for attempted murder," read a Jan. 24 post on image-board website 4chan. "You know what to do /pol/," it continued, referencing a board dedicated to politics.

On Jan. 25, Fellowship of the Minds, a conservative website that has sections labeled "Black Racism" and "Leftwing Pathology," identified Zahory as "most likely" the assailant. It used comments and photos from Zahory's Facebook and Instagram pages to make the connection.

The site also identified the nonprofit where Zahory worked, publishing its address, email and telephone number; naming its CEO; and listing the companies that support it.

Zahory is an Afghani-American and believes many of the people who attacked her online may have mistaken her for Hispanic. She thinks the intense national debate over immigration contributed to the onslaught on social media. The comment section in the conservative Daily Caller filled up with demands that the culprit be deported. Some readers sent the website email naming Zahory as the responsible party. The website debunked the suspicion, telling readers to "leave her alone."

"I don't want to be scared, but at the same time, I don't want to compromise my safety and peace and sanity," she says.

At first she thought the attacks were the work of a random internet troll. Then her boss told her the office was getting calls about the incident. She decided to keep a low profile, shutting down her Facebook page while her friends rallied to her defense online.

"There were all of these usernames attacking me, my character," Zahory says. "I kept saying I didn't do it. I was asking myself, 'Why do all of these people hate me based on the little info they have?'"

Then fear set in.

In early February, her sister and brother-in-law moved into her studio apartment to keep vigil. Her parents, nervous their home could be targeted, moved into a hotel for a week.

Through a friend, Zahory reached out to Brittan Heller, a cybersecurity and hate crimes expert at the Anti-Defamation League, a civil rights organization. Heller, a former federal prosecutor, agreed to help.

Zahory told Heller that she hadn't been near the incident and could prove it. Her uncle and a nurse's aide who helps take care of her ailing father provided photos they'd taken with smartphones. The timestamps clearly showed Zahory with her father at the time.

The evidence convinced the DC Metro Police, which put out a press release on Feb. 16 clearing Zahory.

Still, the emotional damage was done. Zahory hasn't returned to social media, and she just started listening again to songs on Spotify, which requires her to use her Facebook password. She's also grieving for her father, who died in March.

"Anyone who thinks harassment does not have long-term effects has never been a victim," Heller, who had been a target of online abuse during law school, wrote in an email. "It makes it harder for you to trust people."

Therapy has helped reduce some of her panic attacks. Her employer reached out to Reputation.com to scrub the web of at least some of the negative attention she received.

Of course, Zahory longs to go on message boards to defend herself. She'd like to give those who smeared her reputation a piece of her mind. But she knows that probably won't help and could make things worse.

"I miss being online, but that ugly side of the internet -- it's hard to move on from that," she says. "I'm forever changed by this."

In the meantime, DC police say no one has been arrested for the Inauguration Day attack.

Bodyguards and bulletproof vests

Mikey Weinstein began advocating for religious freedom in the military in February 2004, when he learned Protestant faculty members at the Air Force Academy were strongly encouraging the institution's more than 10,000 students and staff to see "The Passion of the Christ."

The Mel Gibson-directed movie, which chronicles the final hours of Jesus, was popular at the box office. But it also drew criticism for being violent, graphic and, to some, anti-Semitic.

Weinstein was concerned his alma mater was pushing students to see a religious movie. So he reached out to the administration to inquire about the reports. He got no response.

An Air Force Academy spokesman didn't respond to an inquiry about the incident when contacted by CNET. He said the academy has no official relationship with Weinstein or the MRFF.

Four months later, Weinstein's youngest son, Curtis, a cadet at the academy, asked to meet him at an off-campus McDonald's for a chat.

"I'm going to beat the shit out of the next guy that calls me a 'f------ Jew.' I'm going to beat the shit out of the next guy that accuses me, or our people, of killing Jesus Christ," his son told him. "I just thought that before it happens, you and Mom should know."

That's when Weinstein decided he had to do something.

When he founded MRFF, Weinstein expected the organization to generate some blowback. America's armed forces have embraced a more diverse set of recruits but remain conservative cultures. Still, he reckoned the repercussions would be brief. He was wrong.

The barrage of intimidation -- blistering phone calls and eye-watering emails -- prompted Weinstein to hire armed bodyguards about 10 years ago. He also keeps attack dogs on his property. He and his wife both carry firearms.

Sometimes that causes problems. In two separate incidents in 2014, police detained and questioned Weinstein and his wife, Bonnie, for carrying loaded weapons into an airport security zone. Weinstein says they simply forgot they were carrying the guns. No charges were filed.

Bonnie, who also gets threats, assembled some of the hatred into a 254-page book called "You Can Be a Good Speller or a Hater, But You Can't Be Both." The title is a reference to the spelling, punctuation and grammar errors that pepper the emails, tweets and posts the couple receives. The communication, Bonnie says, is notable for its hatred of Jews.

"The 'Jew bashing' that is presented here is just incredible to me," she writes in the book.

Over its 11-year history, MRFF's membership has grown to more than 51,000. It includes members of all branches of the military, both active duty and veterans, of all religious backgrounds and sexual orientations. Weinstein has testified before Congress on defending a soldier's right to religious freedom and safeguarding the military from endorsing a single faith.

Weinstein says he got his first hate email in 2004, nearly two years before MRFF opened its doors. He didn't save the message and can't remember the details; he's been attacked so many times they all sort of run together. But he says its contents included multiple references to blood libel, a widely spread medieval myth that Jews use the blood of Christian children to bake Passover matzoh.

That's similar to this one, which he received in late 2014:

"Jewboy don't you evercome back to our state. Your not wanted here. Keep you godam mffr hands off our Holy Univ. of No. Georgia Cadets corps. you f------ jew muslam queer loving jew. servant of satan. Why don't you eat some of your jewbread soked with the blood of innocent Christian children? To make it tasty … "

That's only a snippet of the email. It doesn't get nicer.

Many of the emails and voice messages reference Nazi Germany, specifically mentioning concentration camps. That's particularly troubling to Weinstein, who lost family members in the Holocaust.

The barrage has taken its toll on Weinstein. He's always on edge. You can hear it in his tight voice and the staccato clip of his speech.

The hate he's exposed to makes him careful.

"I don't want the last thoughts in my head, after I've been shot or blown up, [to be] 'You were a stupid idiot and you weren't ready for this,'" he says.

In April, bodyguards accompanied Weinstein when he participated in a debate on religious freedom with Christian speaker Alex McFarland at Colorado Christian University in Denver. Weinstein wore a bulletproof vest.

Why the precautions? Because a campus security guard sent Weinstein a disturbing email before the event. Weinstein reported the email to the debate's sponsors, the Centennial Institute, which notified the school and wrote a letter apologizing. The security guard wasn't allowed to work the event.

The school added metal detectors and local police worked alongside Weinstein's private security personnel.

The debate went off without incident. Weinstein, however, didn't escape judgment.

A female attendee later sent a polite email, praising Weinstein for his intelligence and demeanor. "We expected the worst," she wrote. "I must say however that you were very pleasant and nice."

But she questioned why he needed so much protection and what he had to fear from followers of Jesus Christ. "Was all of that really necessary," she asked, "as this debate was held at a Christian university campus where love is King and not hate?"

She labeled him "the Number One persecutor of Christians who fight" for the US, and she also offered a warning.

"Hell is a real place," she wrote. "It looks like you are going to be a permanent resident there."

This article originally appeared on CNET.