Healthy Hubble raises hopes of even longer life in orbit

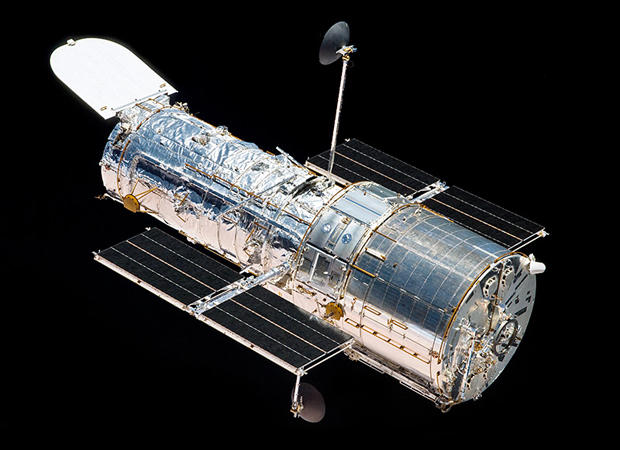

Four years after a final shuttle servicing mission, the Hubble Space Telescope is operating like a fine watch, with no major technical problems that would prevent it from continuing its trail-blazing observations through the end of the decade -- 30 years after launch -- project officials say.

The 2009 space shuttle servicing mission was intended to extend Hubble's life by five years and while engineers and astronomers were hopeful the venerable observatory would remain scientifically viable beyond that target, there were no guarantees.

But other than a handful of relatively minor glitches over the past four years, along with expected degradation in some of its detectors -- degradation that can be offset by operational changes -- Hubble's scientific instruments and complex subsystems are working at near-maximum efficiency.

"I can happily tell you that Hubble has been performing wonderfully since the servicing mission," James Jeletic, deputy project manager of Hubble operations at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, told CBS News.

"The astronauts did an incredible job as well as the teams on the ground that built all the replacement hardware. We have really had hardly any interruptions to date in the last four years. So we've been very, very pleased."

Assuming no major breakdowns between now and the end of the decade, engineers believe Hubble could remain operational well past the launch of its successor, the $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope in 2018. That would allow joint observations and possibly shed new light on the early evolution of stars and galaxies in the wake of the big bang.

"Our requirements were to be able to survive for five years, to do great science for five years following the servicing mission in 2009," Jeletic said. "There's no reason we can't meet that five years. We don't think there's any reason why we're not going to get to do at least a one-year overlap with James Webb."

While engineers don't know what problems might crop up down the road, "Hubble is performing exceptionally well, especially for a 23-year-old spacecraft," he added. "There's lots of things on there that were built before it was launched, obviously, so you're talking 25, 30 years old. ... But as of right now, everything seems to be operating well."

Launched from the shuttle Discovery in April 1990 with a famously flawed primary mirror, Hubble was equipped with corrective optics during a make-or-break 1993 shuttle repair mission.

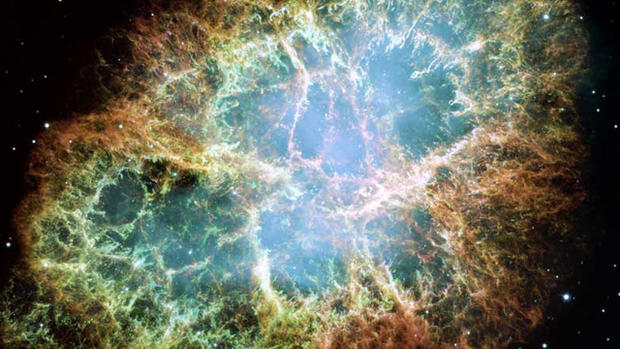

Since then, the Lockheed Martin-built observatory has generated a steady stream of discoveries, ranging from a more precise determination of the age of the universe -- 13.7 billion years -- to confirmation of the existence of super-massive black holes.

In recent years, Hubble's razor-sharp vision has played a key role in the ongoing effort to probe the nature of dark energy, capturing the light from ancient supernovas to chart the accelerating expansion of the cosmos.

But keeping Hubble healthy in the unforgiving environment of space is no small challenge.

During a second servicing mission in February 1997, shuttle astronauts installed two new instruments -- the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph and an infrared camera known as NICMOS -- replaced a fine guidance sensor, a gyroscope assembly and installed a solid-state data recorder.

Because of multiple gyro failures in the late 1990s, a third servicing mission was broken up into two shuttle flights that were launched in December 1999 and March 2002. During Serving Mission 3A, spacewalking astronauts installed a new flight computer, a second solid-state recorder, another fine guidance sensor and a full set of six new gyroscopes.

Servicing mission 3B included installation of two new solar arrays, the Advanced Camera for Surveys, an experimental cooling system to revive Hubble's infrared camera and a replacement power control unit.

NASA was well into planning Servicing Mission 4, the fifth shuttle visit to Hubble, when Columbia was destroyed during re-entry on February 1, 2003, by a breach in its heat shield. A year later, then NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe, siting safety concerns, canceled the final Hubble visit.

Engineers studied possible techniques for overhauling the observatory robotically, but the cost and technical complexity of the proposed mission were daunting at best.

As it turned out, a robotic mission was not necessary. After shuttle crews demonstrated heat shield repair techniques, O'Keefe's successor, Michael Griffin, reinstated the fifth servicing mission.

Finally, on May 11, 2009, the shuttle Atlantis blasted off and four astronauts, working in two-man teams, carried out five back-to-back spacewalks to install six new stabilizing gyroscopes, a full set of six nickel-hydrogen battery packs, a new data computer and two new instruments, the $126 million Wide Field Camera 3 and the $81 million Cosmic Origins Spectrograph.

The astronauts also repaired two other instruments, the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, which suffered a power supply failure in 2004, and the Advanced Camera for Surveys, which broke down in 2007. The instruments were not designed to be repaired in space, but engineers came up with tools and techniques that allowed the spacewalkers to bypass failed electrical components.

The repair crew also installed an upgraded fine guidance sensor, new insulation blankets and a grapple fixture that will permit attachment of a rocket motor at some point down the road to enable a controlled re-entry when Hubble's orbit decays to the point of no return.

In the four years since Hubble was released from Atlantis' robot arm, the space telescope has chalked up a near-flawless performance, operating around the clock with only an occasional hiccup.

Three gyros are required for normal operations with three kept on standby. One of those has shown a slight tendency to drift, but software is on board to compensate and Jeletic said it could be used if necessary. And because of earlier gyro problems, engineers have developed techniques that would enable Hubble to continue doing science using a single gyro if worse came to worse.

All six new batteries are operating flawlessly, as are Hubble's three fine guidance sensors, which help the observatory lock onto its targets. Bearings in the oldest sensor, part of Hubble's original equipment, are showing signs of wear and tear, but Jeletic said flight controllers use it less frequently, with no impact to operations.

The NICMOS infrared camera is off line because of problems with the system used to cool the instrument. While engineers believe they could restart the cooling system and restore the camera to service if necessary, mission managers polled the science community and decided it was not worth the effort.

As it turns out, the infrared channel in the new Wide Field Camera 3 can accommodate most of the observations that otherwise would be carried out by NICMOS "so we decided not to do that," Jeletic said. "Because that would cost us well over a hundred orbits of time to bring it back on line, calibrate it, etc., and we'd rather spend that time taking observations with a different instrument."

The Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph both remain in operation, albeit without full redundancy following their repair during the 2009 servicing mission. The Cosmic Origins Spectrograph and the Wide Field Camera 3 both are operating normally.

Jeletic said most of the instruments suffer from expected but minor degradation in their detectors, ranging from so-called "hot pixels" to a loss of sensitivity. But in each case, engineers have devised ways to work around the problems with little or no loss of science.

Discussing various subsystems, Jeletic said computer processors "freeze" from time to time, requiring ground-commanded re-boots, and cosmic ray particles can trigger so-called single-event upsets in computer circuitry. Such events are believed to be responsible for recorder shutdowns and even "runaway" solar array slews. But in all cases, flight controllers have been able to reset the various systems within a few hours.

"Can we get to 2020 with the current suite of instruments and detectors? The answer, I would say, is yes," Jeletic said. In a subsequent email, he added: "I would be remiss if I don't state that any positive predictions of future success with HST hardware are always stated while we are knocking on wood -- we are a superstitious bunch!"

But Hubble's days are numbered, regardless of its overall health. Based on the latest projections, the space telescope is expected to fall back to Earth sometime between 2030 and 2040, depending on solar activity and its effects on how much altitude-reducing "atmospheric drag" the telescope experiences.

But that is a concern for the future. For now, Jeletic and the team at Goddard are content monitoring Hubble's health, developing contingency plans and making sure the telescope remains operational as long as possible.

"As a kid who grew up in the Apollo days, my goal in life, my dream, was to be able to be part of NASA and make discoveries across the universe, however that was, whether that was with spacecraft, whether that was with manned missions, or whatever," Jeletic said.

"So right now, I'm living my dream. I tell my kids every day, how many people wish they had the opportunities that I have right now to work on Hubble? There's only so many of us who get to do so. We're very blessed."

Editor's note: This article was corrected to state that the Hubble was launched from the shuttle Discovery in April 1990, not Atlantis.