Employee fired for sending false Hawaii missile alert; emergency official resigns

NEW YORK -- Vern Miyagi, the administrator for the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, has resigned in wake of a false alert that was sent earlier this month warning of an incoming ballistic missile, Maj. Gen. Joe Logan announced during a news conference Tuesday. The employee who sent the alert has been fired and another is in the process of being suspended without pay.

Logan, the agency's director, said Miyagi submitted his resignation Tuesday morning and he accepted it. Logan also said the "button pusher" has been terminated.

The employee who sent the alert -- creating a panic across the state -- thought an actual attack was imminent, the Federal Communications Commission said earlier Tuesday. Hawaii has been testing alert capabilities, and the employee for the state Emergency Management Agency mistook a drill for a real warning about a missile threat. He responded by sending the alert without sign-off from a supervisor at a time when there are fears over the threat of nuclear-tipped missiles from North Korea.

"There were no procedures in place to prevent a single person from mistakenly sending a missile alert" in Hawaii, said James Wiley, a cybersecurity and communications reliability staffer at the FCC. There was no requirement to double-check with a colleague or get a supervisor's approval, he said.

In addition, software at Hawaii's emergency agency used the same prompts for both test and actual alerts, and it generally used prepared text that made it easy for a staffer to click through the alerting process without focusing enough on the text of the warning that would be sent.

The worker, whose name has not been released, has refused to talk to the FCC, but federal regulators got information from his written statement that state officials provided.

The alert was sent to cellphones, TV and radio stations in Hawaii on the morning of Jan. 13, leading people to fear the state was under nuclear attack. "THIS IS NOT A DRILL," it said. For what felt like an eternity, islanders heard an audible warning: "A missile may impact on land or sea within minutes. This is not a drill."

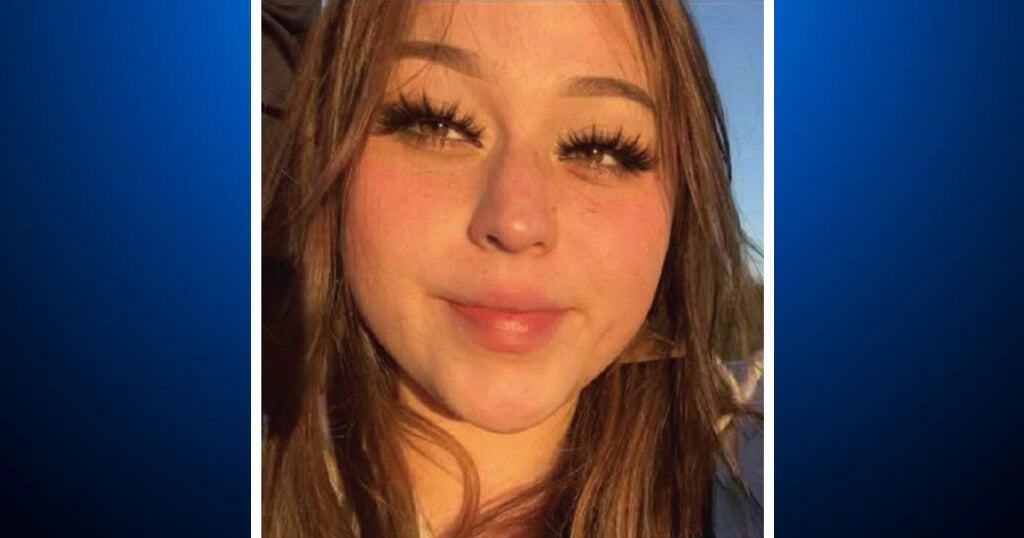

Amanda Thompson screamed when she read the alert. She and her husband threw water and supplies into a tiny closet under the stairs and huddled with their infant and 2-year-old, believing they were about to die.

"We grabbed everything we possibly could -- blankets, pillows, diapers, wipes, food, water bottles -- as I'm crying my eyes out," Thompson said. "We called his parents, and I'm crying so hard that they can't understand me."

It took 38 minutes for officials to send an alert retracting the warning because Hawaii did not have a standardized system for sending such corrections, the FCC said.

The federal agency, which regulates the nation's airwaves and sets standards for such emergency alerts, criticized the state's delay in correcting it.

The head of the FCC has called the error "absolutely unacceptable."

Earlier this month, Miyagi gave CBS News correspondent David Begnaud a tour of Hawaii's Emergency Alert Command Center and discussed what went wrong. During their conversation, Miyagi explained cellphone users weren't told about the error sooner because his agency didn't have procedures for issuing corrections.

That has since changed — and two people will now be required to send out alerts in the future.

The FCC said the state Emergency Management Agency has already taken steps to try to avoid a repeat of the false alert, requiring more supervision of drills and alert and test-alert transmissions. It has created a correction template for false alerts and has stopped ballistic missile defense drills until its own investigation is done.

According to the FCC inquiry, the recorded message used for the drill began by saying "exercise, exercise, exercise" -- the script for a drill, the FCC said. Then the recording used language that is typically used for a real threat, not a drill: "this is not a drill." The recording ended by saying "exercise, exercise, exercise."

However, the worker on duty did not hear the "exercise, exercise, exercise" part of the message and believed the threat was real, according to the employee's statement. The worker responded by sending the alert.