State Department, CIA establish federal payment rules for "Havana Syndrome" victims

Some American diplomats and intelligence officers suffering from the mysterious neurological affliction known as Havana Syndrome may be eligible for federal compensation ranging from about $140,000 to $187,000, according to draft rules published by the State Department on Friday. Though the guidelines are a step forward for those suffering from the syndrome, concerns about disparate treatment of victims of the poorly understood condition persist.

According to the State Department's text, current employees, former employees and their dependents who have "qualifying injuries to the brain" may be eligible for a non-taxable, one-time, lump sum payment pegged to senior government salary levels.

The base level payout is currently $140,475. Victims who demonstrate no reemployment potential, have been approved for Social Security Disability Insurance or require a full-time caregiver can receive up to $187,300. Those amounts, like federal salary levels, could change over time.

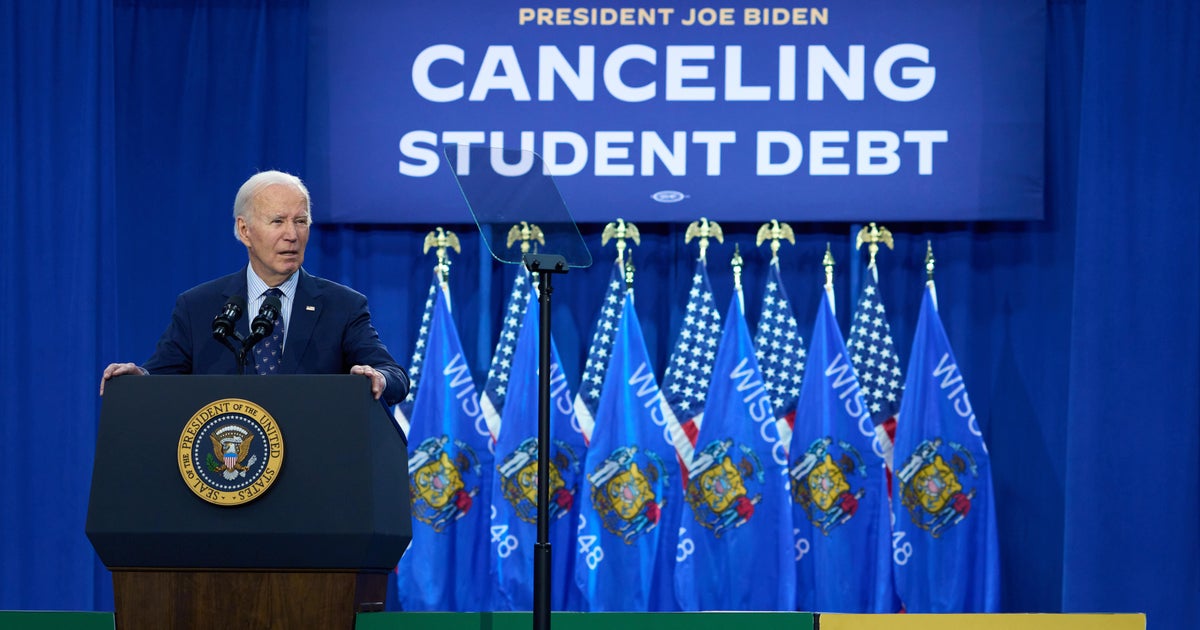

The guidelines were required by a law passed unanimously by Congress and signed by President Biden last year known as the HAVANA Act, which authorized funds for victim compensation and tasked federal agencies with regularly updating lawmakers on reported cases. The legislation allowed the State Department, CIA and other agencies with affected personnel to establish their own eligibility criteria for compensation. That compensation is not related to or a replacement for the provision of medical care for victims, U.S. officials stressed.

While the CIA has also established its own criteria for affected personnel, they remain classified. People familiar with the matter said the agency's guidelines were fairly similar to those drafted by the State Department, and that there would be internal processes in place to connect with former employees interested in reviewing the criteria and determining their eligibility.

"CIA developed guidelines in partnership with the interagency, as part of a process coordinated through the National Security Council, and is beginning to implement these authorities," said CIA Director of Public Affairs Tammy Thorp. "We are grateful to Congress for continuing to support CIA's workforce including through the HAVANA Act."

Symptoms of Havana Syndrome can include intense headaches, nausea, vertigo, tinnitus and cognitive difficulties. The syndrome was first identified among U.S. and Canadian officials stationed in Havana, Cuba, in 2016, and has no known cause. Several government-led inquiries have determined directed radiofrequency energy to be the most plausible source of the condition, and deemed it unlikely to be psychosomatic or attributable to mass hysteria.

Some victims and lawmakers are convinced the incidents are the result of intentional attacks by a hostile government using directed-energy technology, though no definitive public evidence has emerged to confirm that view.

The illness, instances of which the Biden administration refers to as "Anomalous Health Incidents," received intensified focus as dozens – and then hundreds – of new cases were reported by American soldiers, diplomats and intelligence officers serving overseas in recent years. Reports have been made from every populated continent – sometimes coming in dozens at a time – to total about 1,000, cumulatively, since 2016.

Investigators have since found alternative explanations for the majority of those cases, and have narrowed their focus to a handful of incidents that remain unexplained. In some of the most severe cases, American officials have suffered neurological symptoms so debilitating they were forced to end their careers.

Once the State Department rule appears in the Federal Register, which contains the text of U.S. government laws and regulations, it will be subject to a 30-day period of public comment coordinated by the Office of Management and Budget. Officials said they expected a fulsome response from victims and their families, some of whom have struggled with incapacitating symptoms for years and paid out of pocket for diagnostic and medical care. The CIA's guidelines will not be open to public comment.

"Departments and agencies have worked intensively to develop regulations that can be applied consistently, with compassion, and seek to ensure equitable treatment across the U.S. Government," a spokesman for the National Security Council said. "We remain committed to ensuring that individuals who report an AHI have access to medical care and we will continue to rigorously investigate the cause of these incidents, whether or not an individual meets the HAVANA Act's eligibility criteria."

While expressing gratitude to Congress for the increased attention and resources for the illness, some victims' groups have expressed concern about potential discrepancies among the government agencies' internal criteria, including who might qualify for what level of compensation. The lack of understanding about the causes and manifestations of the condition, and the absence of standardized screening or testing for it, may complicate efforts to determine eligibility, they said.

"There must not be any discernible differences between relevant U.S. government agencies on the criteria used and the implementation of the HAVANA Act provisions," said Marc Polymeropoulos, a former senior CIA officer who fell ill during a trip to Moscow in 2017. "I hope congressional oversight ensures that the criteria are as inclusive as possible of personnel injured by AHIs – it would be tragic if some were left behind."

The State Department's draft rule says the Department "sought to establish a standard that it believes will be broadly inclusive of the types of injuries that have been reported by covered individuals to date."

The long-awaited guidelines come amid what people familiar with the matter say has been a drop-off in reported incidents. While the number of reported cases ballooned amid greater public awareness of the condition in the past year, current and former officials knowledgeable about the trend say new reports have declined significantly since the start of 2022.

The officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, declined to offer explanations for the drop-off, but acknowledged several scenarios were possible. The number of reports could have naturally ebbed following a peak in public attention, they said; a hostile actor, if one is behind the incidents, could have changed course; or, there could be some degree of "re-stigmatization" of the condition that has disincentivized victims from coming forward.

In January, a CIA task force dedicated to understanding the incidents issued what it described as an interim report that concluded it was "unlikely" that a foreign actor was "conducting a sustained, worldwide campaign, harming U.S. personnel with a weapon or mechanism." The task force is said to still be scrutinizing the roughly two dozen "priority" cases that remain unexplained and where a foreign actor had not been ruled out, but no updates to the report are currently expected.

A separate report, issued weeks later by an expert panel convened by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, said the condition could be "plausibly" explained by pulsed, electromagnetic energy, reaffirming previous inquiries into its most likely physical cause. That panel did not consider questions related to attribution, including whether the cases were the result of intentional attacks.