Upward mobility is out of reach for younger generations, most Americans say

Americans are feeling gloomy about their prospects of achieving a higher standard of living, with about half saying it's become harder for them to move up the economic ladder, according to a new poll from the University of Chicago and AP-NORC. About 54% of respondents also said they don't think younger generations will top their parents' standard of living, the poll found.

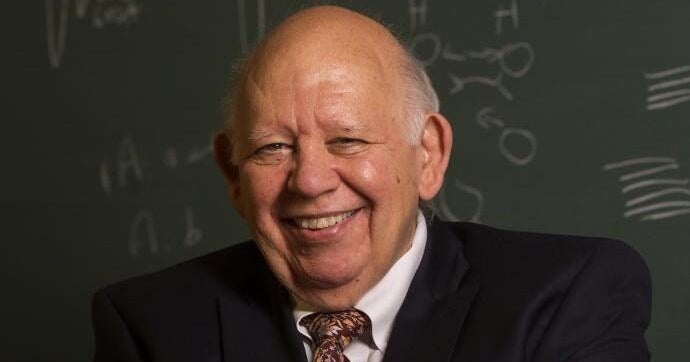

Owning a home and raising a family are cited as important life goals by about 7 in 10 Americans, yet these milestones are also seen as harder to achieve today by more than half of those polled, the study said. That pessimism could reflect ongoing headwinds created by the highest inflation in four decades, as well as a run-up in housing costs, said University of Chicago professor Steven Durlauf, who studies inequality and helped construct the study.

But the negative outlook also could reflect long-term economic trends in the U.S., including widening income and wealth inequality as well as wage stagnation for some types of workers, such as White men.

"There are dimensions where one would say things are harder," Durlauf told CBS MoneyWatch. There are "consequences in shifts in the jobs that people have and the hollowing out of jobs that are in the middle that are good."

He added, "A subset of the population — to be blunt, White males — will experience some relative status reductions," which could be reflected in the poll.

Racial difference in attitudes

Black adults are more optimistic about the possibility of upward mobility than White Americans, with the survey finding that 43% of the former say it's easier for them to achieve a good standard of living compared with their parents, versus 28% of White people who said the same.

The higher level of optimism among Black Americans "reflects an important fact — that even with the background of the history of terrible things done to African-Americans and contemporary issues of discrimination, there are in many dimensions substantial progress in the African-American community," Durlauf said.

Another major gap between respondents boiled down to political affiliation, with Democrats and Republicans citing differences in what influences a person's ability to improve their standard of living.

Almost half of Democrats said a college education is important, compared with 31% of Republicans. By contrast, 87% of Republicans said hard work is key, compared with 76% of Democrats.

The tendency to discount the value of a college education by Republicans is troubling given that higher education typically leads tto higher lifetime earnings, Durlauf said. Meanwhile, the average income of people with only a high school degree has declined 12% over the past four decades.

"When you make the observation that Republicans don't believe that getting a college education is a key step, that says something about the likely decisions that will be made for kids" by their parents, he added.

Inflation and the midterms

Public pessimism about people's economic status may highlight some of the political risks as the midterm elections approach, Durlauf noted.

Josean Cano, 39, a bus operator in Chicago who is Hispanic, said he's had a harder time economically than his parents. He mentioned inflation, high housing costs and the recent baby formula shortage as examples.

"Things have doubled and tripled in price, " he said. "We're not talking about gym shoes or concert tickets. We're talking about essentials. Six months ago, you couldn't find PediaSure. And if you could find it, it would be $20. It used to be $11 at Target."

Cano also pointed to the diminishing purchasing power of the federal minimum wage, which has remained $7.25 an hour since 2009, and that rents and the cost of education were more reasonable in the past.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, the federal minimum wage in 2021 was worth 34% less than in 1968, when its purchasing power peaked.

—With reporting by the Associated Press.