At elite Groton School, "unusual" headmaster puts focus on inclusion

GROTON, Massachusetts — Whether it’s early morning and he’s on his way to chapel, or walking from class to lunch at the school cafeteria, Temba Maqubela is always stopping along his route to speak with students.

“Mr. Maqubela is incredibly warm. That’s the best way to describe both he and his wife. They genuinely want to know how you’re doing, what your story is,” said Jack McLaughlin, an 18-year-old senior at The Groton School, a boarding school in northern Massachusetts.

Groton is an independent school founded in 1884 with the purpose of educating the sons of elite New England families. It’s been co-ed since the 1970s and currently has 380 students, most of whom are boarders, in grades 8-12. Over the years, Groton alumni have gone on to prominent roles in public service. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt went there, as did cold war strategist and secretary of state Dean Acheson.

These days, the school is supported by a $350 million endowment and overseen by a board of 25 trustees, including Maqubela – Groton’s eighth headmaster and something of a departure from his predecessors.

“I’m an unusual headmaster of Groton School, if I may say so myself,” said Maqubela, smiling behind his large desk in the headmaster’s office. To his left, a large window framed the expansive grounds of the school.

At a time when tuition costs at independent schools and colleges across the country are outpacing inflation, Maqubela and his wife Vuyelwa – who teach chemistry and English, respectively – have made it their mission to focus on inclusion and affordability. Their frequent talk of inclusion has led many in the Groton community to dub it the “i” word.

“I think the dirty little secret is that we all call it the “i” word unless we’re in Temba’s presence,” joked Stephen Hill, a trustee who graduated from the school in 1980. “When I went to Groton there wasn’t much diversity,” he added. “Temba’s attempt to make every student feel not just welcome but part of the fabric of Groton is really different about where it is now.”

Long road to Groton

Prior to Groton, the Maqubelas spent 26 years at Phillips Academy Andover, another elite New England boarding school. But their life as educators began in very different circumstances, in South Africa, amid the racist regime of apartheid.

“If you’ve ever been excluded, you never, ever want to see another person excluded,” said Maqubela. “Apartheid was government-sponsored exclusion.” His opposition put him in jeopardy.

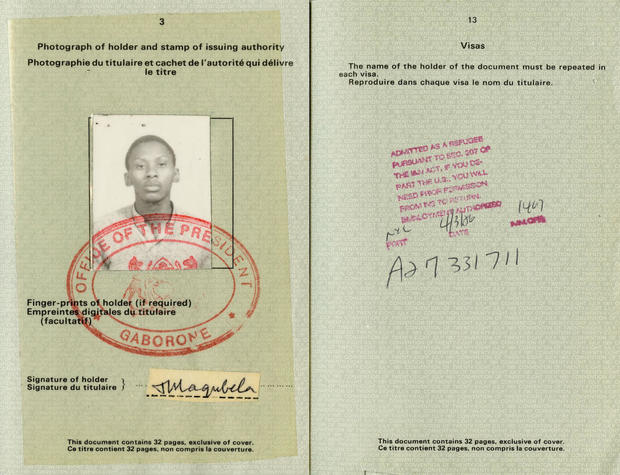

Maqubela fled to Botswana in 1976, following his arrest during a biology class at St. John’s College in the town of Mthatha, South Africa. It was his final year of high school and his mother happened to be teaching that class. Maqubela’s family tree includes prominent educators and political activists. His maternal grandfather became the first black man to earn a degree from a South African university and went on to study and teach in the U.S..

“I was 17 when my country rejected me, when I went inside so many jail cells just because I am South African, and I’m black,” Maqubela told CBS News. He described how he spent a decade in hiding in Botswana and Nigeria, where he earned a degree in chemistry from the University of Ibadan.

“I remember going to visit him, and the [border] guards would sometimes recognize me and detain me so that they would make me wait overnight to cross the border,” said Vuyelwa Maqubela. The couple married in Botswana in early 1985, following several years of long-distance courtship, mostly through letters.

Later that year, their firstborn son was only a few months old when the young family narrowly escaped a massacre known as the Raid on Gaborone, when the South African military targeted anti-apartheid activists in Botswana.

Shortly thereafter, the Maqubelas were granted political asylum in America. They arrived to a homeless shelter in Manhattan, and moved to their first apartment in the South Bronx.

“We came back [to visit the apartment] in April,” said Vuyelwa Maqubela, on an October afternoon in New York City when the Maqubelas were in town for Groton’s annual “alumni and friends” dinner. This year marked their 30th anniversary of being in the U.S., and the dinner was held at the American Museum of Natural History in honor of the fact that Temba Maqubela’s first job in New York was at the museum’s coat check.

The morning after the dinner reception, the Maqubelas went back to the Bronx again and reflected on that journey.

“I’m beginning to feel the emotion now too,” Vuyelwa said to her husband. “The things this brings back to me is how safe we felt –coming from a country where we were not safe. The people around here took care of us.”

“More kids from neighborhoods like this should be given the opportunity to attend schools like Groton. ... And that’s what hopefully our legacy will be,” the headmaster said.

Since coming to Groton in 2013, the Maqubelas have spearheaded several measures in an effort to make the school more accessible to lower and middle income students, largely through two programs known by the acronyms GRACE and GRAIN. These include securing an additional $50 million for scholarships, withdrawing a higher sum from Groton’s endowment fund, and initiating a three-year tuition freeze that they’re halfway though. Tuition at Groton currently runs from $44,390 to $55,700, including room and board.

“It is expensive,” said Maqubela, acknowledging that baseline tuition remains prohibitive for most American families: “But by the same token I would say we are doing something about it.

“My predecessor declared that families who earn $75,000 or less will be able to send their children to Groton for free,” he said. “Right now we have our new initiative, to ensure affordability for those families I would call the deserving, missing middle.”

Since GRAIN was announced in late 2014, the number of black, Latino, and multiracial students increased by 43 percent, from 60 to 86 students. In that same period, the financial aid budget increased just over eight percent to $6.32 million.

Maqubela emphasized how he considered it crucial to additionally focus on “the talented missing middle” - families who are by no means poor but who believe that they cannot afford independent school tuition. Last year, Groton provided financial aid to 49 families earning between $120,000 and $300,000. This year aid was provided to 66 such families.

“Inclusion is almost tantamount to perfection – an ideal you’re always working towards,” he added. “The day you say you’re satisfied is the day you start excluding people.”

A model effort

Some experts remain skeptical of the overall effect that efforts like Maqubela’s will have on opening up access to such exclusive schools.

“I think Temba is in some ways without reproach for wanting and desiring to bring in a conversation about diversity to an elite American institution like Groton,” said David Kirkland, director of the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education & Human Development. “However, it’s not clear to me that those students will apply to Groton because for so long they’ve seen institutions like Groton as not for them.”

Back in the headmaster’s office at Groton, as Maqubela prepared to teach an advanced chemistry class, he insisted that Groton’s push for inclusion could – and should – serve “as a model” for others schools and colleges across America.

“There is no correlation between how much money you have and your talent. But it’s going to take schools like Groton that have had a traditional responsibility because of their resources – take that privilege and use it to show how schools can be inclusive,” said Maqubela.

He described new efforts to get more diverse prospective students to visit the campus: how the school was hosting its first open house, and how students were being bused from New York City in an attempt to attract young people from lower- and middle- income neighborhoods who might never have considered a school like that before.

“To tell you the truth, as much as I love Groton – and I love Groton – if it was just for the students, for Groton, I wouldn’t be as passionate as I am now.”