"Greedflation": Is corporate profit-taking driving prices higher?

At Sugar Hill Creamery, in Harlem, the hand-made ice cream will cost you more these days, because, according to owner Petrushka Bazin Larsen, everything costs her more. "Everything is going up, from dairy, milk and cream, to just our cups," she told correspondent David Pogue. "Costs me more to get the cups here than it is for the cups. Do you know what I'm saying? The freight charges are gastronomical!"

No matter what business you're in, your costs have gone up, for all kinds of reasons. For Dariusz Paczuski's vodka company, Rocket Vodka, the costs of the glass itself, "depending on the size of the bottle, are up 17% to 25% on the larger size bottles."

At Caroline Morris' gift shop, Kimman's Co., she said, "My vendors, where they might have paid $3,000 for a container for shipping, are now paying $30,000."

Al Underwood said that a couple of years ago tariffs affected his reading-glasses supply store, Franklin Eyewear: "It's 10%," he said.

So, what's going on? As you may recall, prices are a function of supply and demand. More demand, higher prices (as demonstrated last year for "Sunday Morning" by the David Pogue Thespian Ensemble):

Harvard professor Larry Summers (who was Treasury Secretary during the Clinton administration) predicted this year's inflation over a year ago. "We put much too much demand into the economy last year," he told Pogue, "and inevitably that was gonna cause it to overheat, which it has.

"The combination of pumping trillions and trillions and trillions of stimulus money, and the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates at zero, all of that taken together was, I think, inevitably gonna drive the car much too fast and cause it to go off the road," said Summers.

Then, in an unhappy coincidence, the supply went down, too. "The big increases in prices have much more to do with shortages," Summers said.

Supply and demand, both way out of whack. But lately, we've been hearing about a third contributing factor: companies exploiting the situation.

"There's a third set of arguments people make that some firms are able to somewhat opportunistically raise prices in the midst of all this chaos, given those other two factors," said Mike Konczal, an economist at the Roosevelt Institute.

It's a concept dubbed "Greedflation."

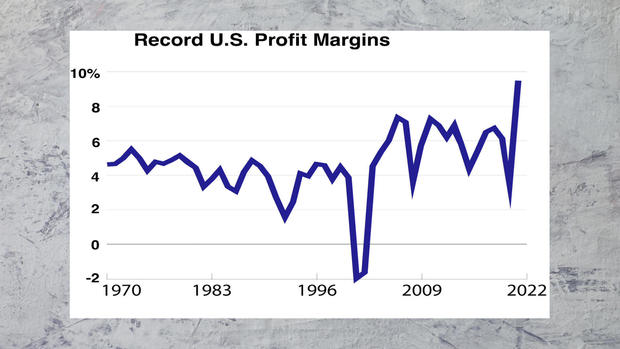

In a new study, Konczal graphed corporate profit margins over time:

"Their big profit margin has gone from about 5% over the last several decades to almost 10% in the past two years," he told Pogue. "So, there's been a giant jump in corporate profits essentially during the pandemic and during the recovery."

- U.S. companies just had their best year since before most of us were born

- As inflation soars, major corporations are posting record profits. But small businesses are feeling the squeeze

- Major retailers accused of profiteering from rising inflation

"Sunday Morning" has been so far unable to get any of these companies with record profits to speak to us for this story. "I'm shocked! I'm shocked!" quipped Robert Reich, a professor at Berkeley who was Labor Secretary during the Clinton administration.

Pogue asked, "What would they say their rationale is for raising prices unduly at a time when we can least afford it?"

"Well, they would say, 'Our obligation is to our shareholders,' and that's it," Reich replied.

So, everyone agrees: corporations have raised prices as high as they can get away with. But not everyone agrees that there's anything wrong with that.

Reich said, "I wouldn't call it greedflation, quite honestly. I mean, companies are responding to what the incentives are in the market, and they have to maximize their shareholder returns. That's it."

Pogue said, "Wow, I thought that you really felt like these corporation leaders are being exploitative and unfair?"

"I don't use the term unfair," Reich said. "It's not a matter of morality. The corporations are not people. They are going to maximize their share prices; that's what they do. But the result has been extraordinary price inflation."

Or, as Larry Summers puts it: "Resorts in Miami charge more in the winter than they do in the summer, and have larger markups. That doesn't mean they're gouging. It means that sometimes there's more demand relative to supply. So, I think this idea that prices being raised in the face of strong demand constitutes gouging is a real misconception."

"You make it sound like capitalism is working like it's supposed to: supply and demand determine prices?" asked Pogue.

"Yeah," Summers said. "Look, we have a market economy, and we haven't found alternatives to a market economy that are better."

But that doesn't mean we're helpless. In a perfect market economy, if you charge too much, competitors will rush in and steal your customers.

But our market isn't perfect. Reich said, "Since the 1980s, two-thirds of American industries have become more concentrated. We have more and more monopolization, more and more market power, more and more power by big companies to set prices."

"But I thought there's antitrust laws," said Pogue. "I thought the government's supposed to protect us from that?"

"Well, you would think so," Reich replied. "But since the 1980s, antitrust law has become very unfashionable."

- Judge dismisses federal antitrust suits against Facebook

- Biden signs executive order cracking down on anticompetitive economic practices

So, how do we rein in this wild inflation? "The government can, and should, do much more," said Reich. "The threat of antitrust enforcement, combined with a windfall profits tax, right there, you have almost enough."

Summers said. "I think the executive branch and the Congress can make a contribution by reducing tariffs, by figuring out how to buy things more inexpensively, by increasing the supply of commodities that are in short supply."

There is some good news. Gas prices have recently started to drop a little bit, and so have shipping prices.

Meanwhile, analyst Mike Konczal has good news about the economy, if you can get past that inflation thing: "The economy's still very strong," he said. "Spending is still very strong. Job growth is still increasingly high. You know, it's unemployment at 3.5%. This is probably the best labor market we've had in 60 or 70 years."

- Hiring surged in June despite inflation, with 372,000 jobs created

- Companies offering bonuses, flexibility and other perks to fill positions in competitive labor market

Now, we just have to fix the inflation. For ice cream entrepreneur Petrushka Bazin Larsen, that day won't come soon enough: "You know, it's a little harder to do business, right?" she said. "But we are hopeful that it's possible, and that at the end of this, whatever that is, we'll be stronger because of it."

For more info:

- Robert Reich, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley

- Mike Konczal

- Larry Summers

- Sugar Hill Creamery, New York, N.Y.

- Rocket Vodka, El Dorado Hills, Calif.

- Kimman's Co., York, Pa.

- Franklin Eyewear, Ridgeland, Miss.

Story produced by Gabriel Falcon. Editor: Joseph Frandino.

See also: