Grave gardening: Tending more than just flowers

"How Does Your Garden Grow" is the question posed by an age-old nursery rhyme. Tony Dokoupil has our most unusual answer:

Every great summer garden really begins in the winter, with a ritual of seeds and shovels.

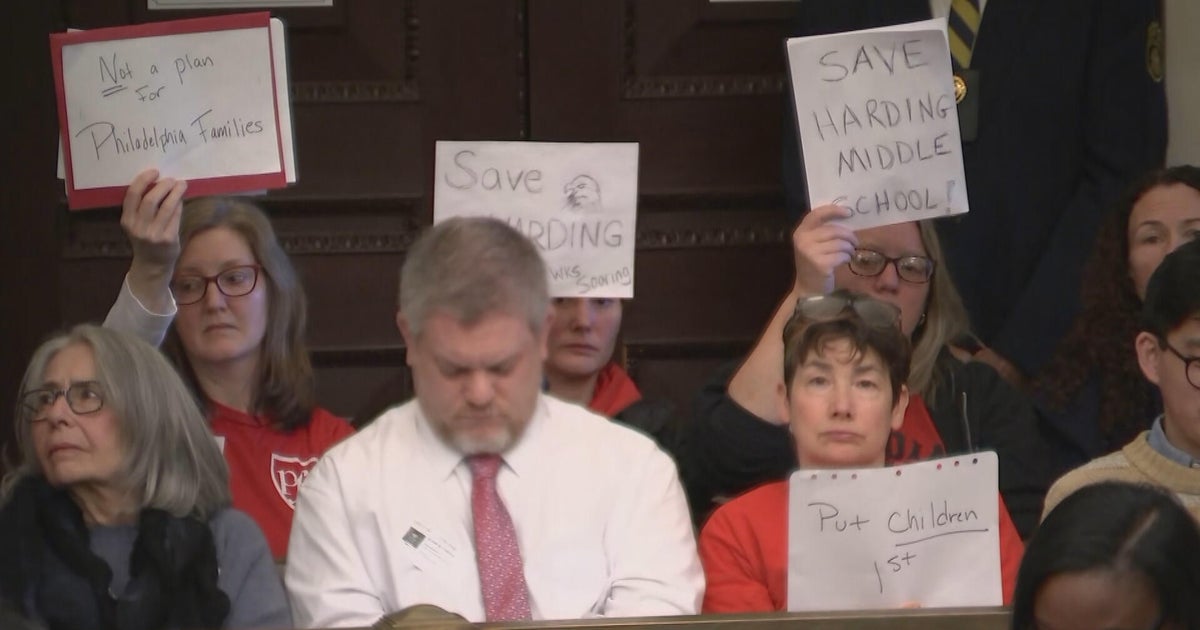

But these gardeners -- volunteers at The Woodlands, a 54-acre oasis in West Philadelphia, have an extra challenge each year.

"Joe is on hand today to help people find their grave," said executive director Jessica Baumert. "Is there anybody that has not found their grave that needs that assistance?"

The Woodlands is a mid-19th century cemetery, which dates to a time when, believe it or not, graves were designed to be planters … and many Americans liked the idea of eternal rest under a bed of roses.

"There would have been flowers virtually everywhere," said Baumert. "Roses. Climbing vines. Families basically would come and they would treat their family's lot as a garden space."

"You would bring your living family to sit here and garden and picnic with the family no longer here?" said Dokoupil. "So it was kind of a reunion."

"Yep."

Baumert says the grounds once contained more than 300 "tombs in the French style," each one a scene of cultivation. "It was in the 19th century when gardening became a hobby activity for people," she said.

But over the years, as families moved away, the weeds moved in. That is, until two years ago, when Baumert put out a modest call for 25 volunteers. She got 75.

And this year, with help from a grant, she expanded to 130 self-described "grave gardeners."

Gardners like literature professor Elizabeth Womack.

Dokoupil asked, "How did it feel the first time you put your hands in the soil?"

"Oh, it was thrilling," Womack laughed. "I mean, there's something really viscerally satisfying about taking a shovel and just digging up a grave."

These days, The Woodlands is buzzing with people, at work and at play, much like it would have been in the mid-1800s, when the cemetery became a popular escape from the noise and pollution of city living.

Baumert said, "This type of cemetery is the earliest form of public park, so this is the place people would come. You actually needed a ticket to get in the gates on the weekend because it was so crowded with visitors. Because So many people were coming here."

Back then, The Woodlands was revolutionary -- a so-called rural cemetery enclosed by trees on the edge of town, instead of urban graveyards crowded by buildings near its center. Such cemeteries, like Green-Wood in Brooklyn, are once again attracting crowds, and offering a valuable change in perspective.

Maya Arthur is a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, and like other Woodlands volunteers she finds two-to-four hours a week for her garden.

Dokoupil asked, "I would imagine that a college term paper would seem like small potatoes if you spend your afternoon in a cemetery."

"Yeah, or, like, medium potatoes," she laughed. "Yeah, try to balance it all for sure."

Arthur's commitment began with mandatory workshops, including Victorian horticulture, so every plant in The Woodlands is true-to-the-era.

For Womack, the most rewarding part of grave gardening isn't really the gardening at all. She often comes here with her three-year-old son ("He especially likes that gravestone that's tipped over a little bit. He likes to run his cars down it"), whose birth brought joy, but also fear: "I was terrified that something was going to happen to him. And it was crippling," she said.

But it turns out that when you garden in an old cemetery, you tend to more than just flowers.

"What I noticed as I started planting there is that, it was allowing me to confront things that scared me," Womack said, "and to nurture this external garden while I nurtured myself."

Even for grave gardeners, there's a lot of life in the soil.

For more info:

- The Woodlands, Philadelphia

- The Woodlands Grave Gardeners (gravegardeners.org)

- Follow Woodlands (@woodlandsphila) on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram

Story produced by Vidya Singh.