"Anything extra, we can't do it," striking GM worker tells her kids

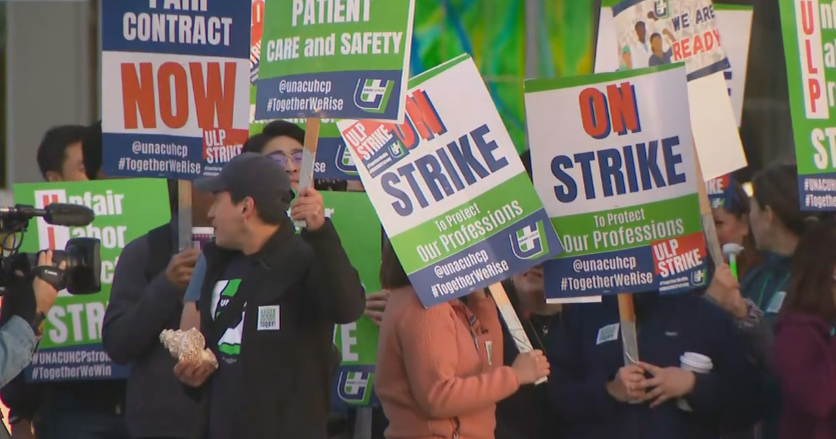

For striking General Motors worker Renee Dixon, the walkout — now in its 19th day — means having to say no to her kids.

"Being able to go to McDonald's for a treat after school — we can't do that right now," Dixon told CBS MoneyWatch while on her way to pick up her strike pay at the union hall near her home in Roseville, Michigan. "I try my hardest to explain to my children, anything extra, we can't do it."

Striking employees at the auto giant get $250 a week from the United Auto Workers, a sum that doesn't come close to replacing their wages. A typical GM worker earns about $30 an hour, or $1,200 per week, according to the Detroit Free Press. And as the strike nears the end of its third week, some workers say they are stressed about paying the bills and are cutting back on spending.

A full-time GM employee for the past three-and-a-half years, Dixon works on a line that assembles doors at GM's Detroit-Hamtramck plant. The company has said it plans to idle the factory starting in January, though it could keep running depending on how talks progress.

The sole provider for her children, who are 11- and 7-years-old, she said the financial hardships of being on strike are worth it if that leads to an improved labor agreement. For Dixon, that largely revolves around job stability. "The people at the table for us know what we want, what we need to ensure a better future," she added.

GM and the UAW resumed contract negotiations Friday morning in hopes of ending the standoff, which has sidelined nearly 50,000 workers. Talks center on health care, wages and the company's use of temporary workers.

Striking GM workers are also receiving support from other union locals and the community, both on the picket lines and in donations of food and diapers left at UAW halls.

"Financial institutions are helping us out — if we're behind, they've told us they are more than happy to work with us," said Amy Penny, a seven-year employee at GM's Lansing Delta Township facility, or LDT, in Lansing, Michigan.

"We're definitely in it for the long haul," Penny added.

GM's tiered system of wages and benefits is troublesome for Dixon and Penny, both of whom earn hourly wages that are capped at about $30 an hour after eight years. That's a step above temporary workers, who make up about 7% of GM's U.S. workforce and who earn as little as $15 an hour.

"I stand next to workers who do the same thing as me, and have been for a year-and-a-half or more, and they still work on a temporary status," Dixon said. "It's hard when we get any kind of bonus, raise or vacation day when these people aren't eligible for that — it's unfair."

The sense of unfairness may be exacerbated by an economy that's in its 10th year of expansion, which has lifted corporate profits.

"Workers are seeing an economy that's doing very well, and workers in many plants have pushed for better conditions and done so successfully," said Bill Spriggs, chief economist for the AFL-CIO. "It's understandable that workers want better conditions when they're seeing companies make huge profits."

GM said in an email that the company is "working hard to reach an agreement that builds a stronger future for our employees and our business." A spokesperson declined further comment.

Striking workers, non-UAW workers and suppliers' workers are losing more than $30 million a day, estimates Anderson Economic Group in East Lansing, Michigan. GM itself could be out $660 million in profits if the strike persists through the weekend, the company added.