Saving the giant panda from extinction

Chinese call them "xiongmao," meaning, "bear that looks like a cat." The adjective they use is "meng" which translates, "cute like a baby." Until recently, the giant panda was on its way to extinction. But then, it was saved by its one evolutionary advantage: it's adorable. In 2016, the panda's conservation status was upgraded from endangered to just vulnerable. Because the giant panda is China's national symbol, the Chinese have worked four decades to perfect breeding the bears in captivity. They've achieved one of the biggest successes in conservation, but there is more work to do. The next step is introducing captive pandas into the wild. That research slowed after a few freed bears were found dead. And, as you are about to see, no Chinese scientist can afford to lose even one baby cute cat bear.

Giant pandas have been chewing bamboo for about 3 million years, but they were so elusive in the high mountains of China, pandas weren't discovered by western naturalists until 1869.

Today their fans know where to find them. Each morning humans compete for position at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding in Central China. A ticket is about eight bucks. Some days there are 100,000 visitors. So, yes, that's $800,000 a day. But the experience is priceless. If these bears were in the wild, they'd be rare and solitary. They would be in alpine forests as high as 13,000 feet and we saw, about 30 feet up, how they went unnoticed for so long.

At the research base, each bear is known by name, liked online and wrapped in the flag. A selfie with China's national symbol, is a tap of patriotism.

Marc Valitutto: When I'm out on the street, and if anybody asks me about what I do, I tell them, "I work with giant pandas," they immediately thank me. And then they follow it up with, "That is our national treasure."

Enriching the treasure is the work of Marc Valitutto, a wildlife veterinarian from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, on loan to the Chengdu Research Base.

The Smithsonian has helped propagate pandas since China sent Richard Nixon home with a pair in 1972. Back then, China barely had two to spare. By the 1980's there were only about 1,200 left, in China's bamboo forests, which humans were cutting down.

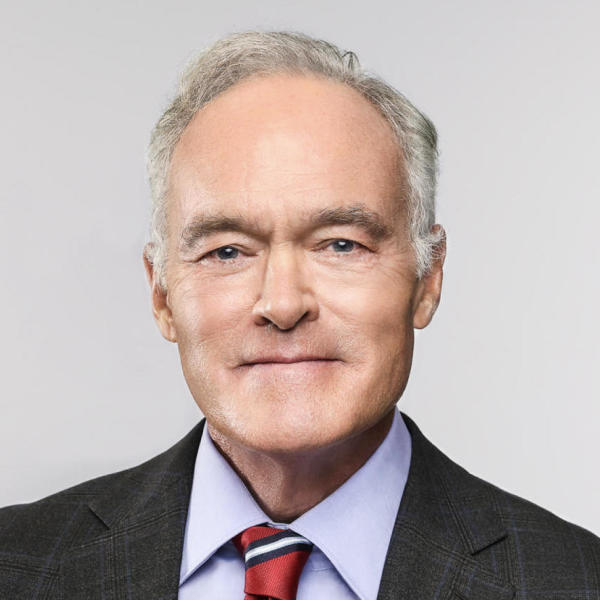

Scott Pelley: Is bamboo the only thing they eat?

Marc Valitutto: 99% of their diet in the wild is bamboo.

A forest is delivered every day to the Chengdu base. The common name, "panda," means "bamboo eater." But because this member of the grass family is so low in nutrition, each bear spends up to 16 hours a day shredding 40 pounds of leaves and stems and that is hardly enough to keep him alive. So, the rest of the day, the bears burn as few calories as possible. Even mating is incredibly rare.

Marc Valitutto: Only once a year can a female be prepared for breeding. And that is within a very small three-day window.

Scott Pelley: A female panda is capable of breeding three days a year?

Marc Valitutto: Exactly. A very small time.

A very small time for a very small bear.

Scott Pelley: and, how old are these cubs?

Dr. Wu Kongju: One month.

Dr. Wu Kongju told us, when these cubs are newborn, they average about four ounces. The size of a stick of butter.

Scott Pelley: And how many cubs do you bring into the world in a year?

Dr. Wu Kongju: This year is five. Five babies.

Scott Pelley: Of the five cubs that are born here this year, how many do you expect to survive?

Dr. Wu Kongju: All.

Scott Pelley: All of them?

Dr. Wu Kongju: All will survive. Yeah.

About half the time, pandas have twins but the mother can't care for both.

Marc Valitutto: In the wild, the smaller, the weaker twin will be left off to die, because the mother doesn't have enough energy to produce the amount of milk that's required for two babies.

But in captivity, twins are fed in the nursery and, with a touch, mom is called to duty, to nurse the twins one at a time so both survive. The cub's eyes won't open for about six weeks so mother helps him to her breast. And like every nursing mom, a change of position helps.

Especially, when her back is killing her.

The cubs are dependent up to three years. She'll raise only five, or maybe eight, in her lifetime.

Scott Pelley: How big do they become?

Marc Valitutto: So, the females can be up to maybe around 200 pounds, and the males up to 300 pounds.

Scott Pelley: Why are they black and white?

Marc Valitutto: You know, that's a very interesting question. It's a mechanism to protect themselves, like many, many other animals out there that are black and white or various different colors.

Scott Pelley: It's camouflage?

Marc Valitutto: You know pandas love the snow. So, the white parts really helped them hide in the snow, where the black would be presumptive of shadows.

The panda is a curious bear. In the last century, many biologists didn't think it belonged in the bear family. Pandas don't hibernate. And though they're virtual vegetarians, they have the digestive tract of a carnivore. Panda nutrition was a mystery when Dr. Hou Rong came here nearly 30 years ago. She's director of research and told us that the base started as a shelter for injured pandas that had been rescued.

Dr. Hou Rong (Translation): There were very few pandas. All of them were seriously ill, close to impossible to breed, we were also broke. I was the only scientist.

Scott Pelley: You had a dozen pandas?

Dr. Hou Rong: Yes.

Scott Pelley: How many do you have now?

Dr. Hou Rong: Now is 200.

200 healthy pandas have grown from the research into nutrition and understanding those fleeting female hormones. It's gone so well that a new area of research has opened: panda geriatrics. The bears live about 20 years in the wild but up to 35 in the company of man. In 1937, a leading American naturalist described the giant panda as "an extremely stupid beast, dull and primitive." But Marc Valitutto showed us pandas understand commands.

The whistle signals something good is about to happen, generally involving apple slices. Then, on cue, the bear volunteered its arm, through the bars, to a metal tray and gripped a handle. It's having a blood test.

Marc Valitutto: All of the pandas, the adult pandas here, are trained specifically to offer their arm for a blood sample. It really helps us to prevent the animals from having to be anesthetized and allows the animal to be an active participant in their health.

Scott Pelley: I've seen people throw a bigger fuss than he did.

Marc Valitutto: They're incredibly complex creatures, just like many other bear species or carnivorous species like dogs and cats.

Like dogs, pandas come at the sound of their name. They know their day will start with apples and continue at the endless bamboo buffet.

But success in captivity does not necessarily mean salad days for the species. To thrive, genetically, they must come home to the wild.

Melissa Songer: This is really an exciting time, because they're doing so well in captivity. And we can really consider them safe. That's not so for the wild populations.

Melissa Songer is a Smithsonian conservation biologist working at the foot of Mount Qingcheng, near the center of China.

Melissa Songer: This is the Chengdu Field Research Center and most people know it as Panda Valley. And it was established for the purpose of preparing captive pandas for release into the wild.

Scott Pelley: One of the amazing things that we saw is how well trained they are. But it strikes me that that's a blessing and a curse.

Melissa Songer: They don't have the opportunity to learn how to find food or defend against predators. Even mating is very complex in the wild. So yes, they're highly trained, but they aren't really trained to be in the wild.

Scott Pelley: Then do you train them to be wild? And-- and if so, how do you do that?

Melissa Songer: They're not going to be fed. They're going to have to move around and find food. And taking it step by step so acclimatizing them to a very different situation is an important phase before full release.

Scott Pelley: Like sending the kids off to college.

Melissa Songer: Yeah. Exactly.

There are fewer than 2,000 wild pandas, living in only three mountainous provinces of china. They're segregated into small groups, cut off from one another by roads, farms and villages.

Melissa Songer: About half of those populations are less than ten pandas. And so that kind of puts them at risk for losing genetic diversity, it puts them at risk for other events, natural disasters, diseases that might come through. So, it's a dangerous number.

To reduce the danger, two research bases are testing competing ideas. One, from a research station called Wolong, minimizes contact with people, to the point of dressing the trainers in panda suits that are scented with panda urine so the bears don't even get a whiff of humanity. The other approach encourages the human relationship, in case a panda needs to be rescued. While the bears walk on the wild side, they're monitored with radio collars in case they get into trouble.

So far, 14 pandas have been released, three have died. But those few failures have slowed the research because if a panda is killed, it's not just some 'bear,' it's a bear with a name, and a million "likes" on its webpage.

Melissa Songer: Any time you release a captive animal to the wild you're taking a risk. And you prepare as best you can, but there are things you can't really prepare for.

One of the pandas who died was attacked by dogs, another appears to have fallen from a tree. The captive-born pandas take longer to establish territory but, for the most part, they fit in. China says it will soon spend more than a billion dollars on a 10,000 square mile panda national reserve to connect those pockets of wild bears.

Scott Pelley: It suggests that species can be saved.

Marc Valitutto: It absolutely does. But more than that, what's even better than the survivability of this species is that they are an umbrella species, meaning that the care that we provide for the pandas and the tracts of land that we preserve, will also save a whole multitude of other species that also need our care, that a lot of people don't even know about.

Which raises a fair question. If a multitude of species is saved, if climate benefits from five million acres of forest reserve, are we saving the panda or is the panda saving us?

Produced by Nicole Young. Associate producers, Katie Kerbstat and Ian Flickinger