The Good Friday Agreement

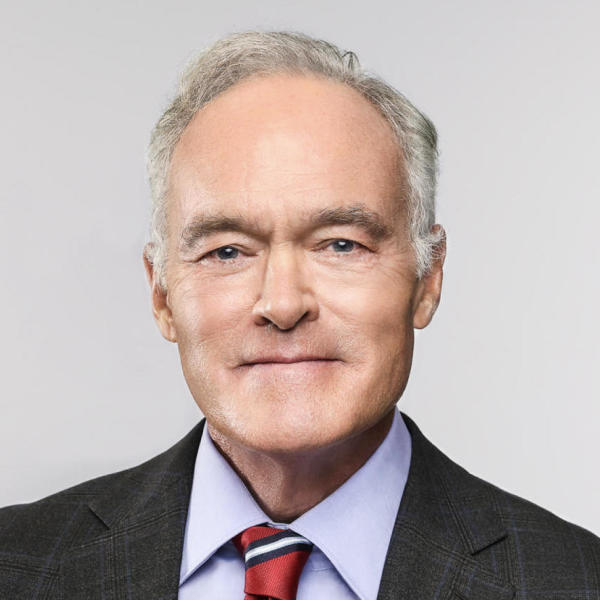

The following script is from "The Good Friday Agreement" which aired on April 5, 2015. Scott Pelley is the correspondent. Patricia Shevlin, producer.

Eastertime marks the end of one of the longest wars of the 20th century. It was known as The Troubles -- for 30 years, Catholics and Protestants murdered one another in Northern Ireland until the Good Friday Agreement resurrected the peace. That truce has held for 17 years but it's tested every day because forgiveness was never part of the deal.

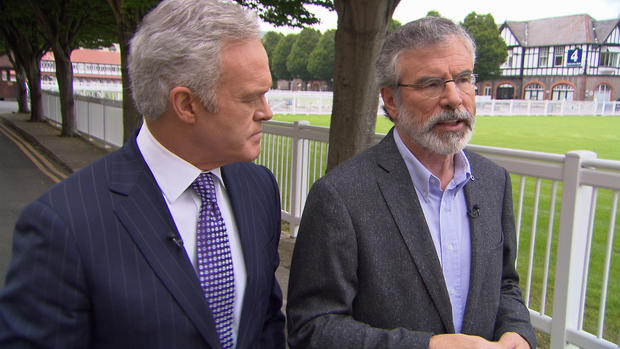

Recently, old wounds split open when a history project by Boston College uncovered accusations of murder against the man who could be Ireland's next prime minster. Gerry Adams heads a leading political party called Sinn Fein. But he was also a central figure in the civil war. Now, just as the truce was beginning to look bulletproof, the Boston College project threatens both Adams and the peace he helped create.

Scott Pelley: Do you think you will see a united Ireland?

Gerry Adams: If I live long enough, yes.

"My position has been very, very clear for a very, very long time. I don't dissociate myself from the IRA. I think the IRA was a legitimate response to what was happening here."

About Gerry Adams this much is agreed, in the 1960s he was a young revolutionary bound closely to the Irish Republican Army, the IRA -- a Catholic militia at war with the Protestant majority in Northern Ireland. The next part is what his enemies find so hard to believe.

Scott Pelley: Some say that you were a leader in the IRA.

Gerry Adams: My position has been very, very clear for a very, very long time. I don't dissociate myself from the IRA. I think the IRA was a legitimate response to what was happening here.

Scott Pelley: I want to make sure I understood you clearly. You don't associate yourself or don't disassociate yourself?

Gerry Adams: No. I don't dissociate myself from the IRA and I never will. But I was not a member of the IRA.

Scott Pelley: Did you ever pull a trigger?

Gerry Adams: No.

Scott Pelley: Set a bomb?

Gerry Adams: No.

Scott Pelley: Order a death?

Gerry Adams: No.

Scott Pelley: So you were at the top of Republicanism nearly throughout The Troubles, and your hands are clean?

Gerry Adams: Well, it depends. That's an evocative term. Your hands are clean.

Scott Pelley: No blood on your hands is what we mean.

Gerry Adams: Well, we all have our responsibility. All of us.

Answers like that, dodging into fog, infuriate his enemies and raise suspicions in others. Adams always said that he led the IRA's political party, Sinn Fein. A diplomat, he says, not a general.

The blood of The Troubles flowed mainly in the streets of Belfast. In the 1960s, Catholics, long discriminated against, rebelled against British rule. Northern Ireland had remained a part of Britain after Irish Independence in 1920. About 3,500 were killed, 50,000 were maimed. In 1998, the U.S. brokered the truce. Adams made the Catholic IRA drop its weapons and submit to a still divided Ireland.

But, the language of that peace contract is as ambiguous as a Gerry Adams interview. It papers over unsolved crimes including an infamous murder in which Adams himself is a suspect.

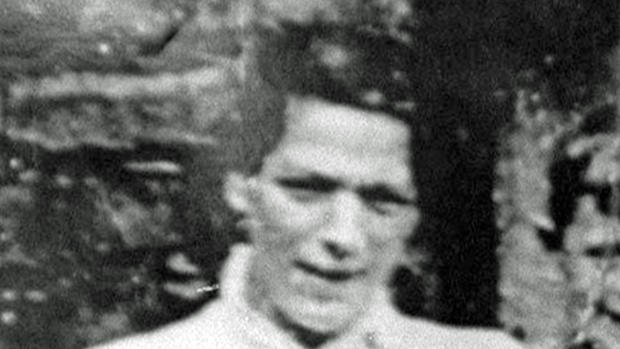

The ghost of Jean McConville has been restless since 1972 when the widow and mother of 10, was accused of being an informer for the British and was dragged from her apartment by several IRA soldiers. This is her daughter, Helen, at the time, with some of her brothers and sisters.

"...I always said that the night they took my mother they should have come in and took the whole family because that's what they did, they destroyed the whole family."

[Reporter: Helen, I believe you're looking after the family, how are you managing to cope?

Helen: OK.

Reporter: When do you think you'll see your mommy again?

Helen: Don't know.]

Today, Helen, Helen McKendry, is a grandmother who can't fully explain the disappearance.

Scott Pelley: You and your siblings went to different orphanages?

Helen McKendry: We did yeah. We were split up.

Scott Pelley: And the family was really never reunited.

Helen McKendry: No. We never were. And I always said that the night they took my mother they should have come in and took the whole family because that's what they did, they destroyed the whole family.

Now, Helen McKendry is the leading symbol of the Good Friday Agreement's painful compromise. Justice for some families was sacrificed to make peace for everyone. A code of silence around unsolved atrocities kept that peace. And it worked, for most, until Boston College pried open the past.

In 2001, the university did what the Good Friday Agreement tried to avoid. In a secret effort, called the Belfast Project, researchers for Boston College recorded the details of The Troubles in oral histories with 40 aging fighters from both sides.

Ricky O'Rawe: I thought it was a great idea. It gave us an opportunity to leave a testimony of what happened, personal testimony of what my involvement in the IRA armed struggle.

[Ricky O'Rawe: That used to be a police station.]

Ricky O'Rawe was among those willing to break the code of silence because, like all the rest, he was told the tapes would remain sealed until he was dead. O'Rawe was in the Catholic IRA and shortly after he married he was arrested for robbing a bank to fund the cause. He was among the IRA inmates at Long Kesh Prison -- including Gerry Adams and Adam's close friend Brendan Hughes. O'Rawe ran a hunger strike that led to the deaths of 10 IRA prisoners.

Ricky O'Rawe: For me that was the darkest period of my life.

How many hours of interviews did you do for the Boston College project?

Ricky O'Rawe: I would say, perhaps about 20.

Scott Pelley: 20 hours?

Ricky O'Rawe: Yeah.

Scott Pelley: And what did you expect to happen to those tapes?

Ricky O'Rawe: I expected never to hear from 'em again. I had absolutely no inclination or no indication that they would ever emerge in my lifetime.

But emerge they did after the first interview subject died in 2008. It was Brendan Hughes, Adams' friend and a notorious bomber.

[Brendan Hughes: There's a woman that went missing.]

His tapes were made public. And included one last bomb.

[Brendan Hughes: This woman was taken away and executed by the IRA.

Interviewer: Jean McConville.

[Brendan Hughes: Jean McConville. There's only one man that gave the order for that woman to be executed. That f**** man is now the head of Sinn Fein.]

"The head of Sinn Fein," Gerry Adams. Hughes and Adams had had a falling out over the peace agreement. In 2011, Northern Ireland police subpoenaed the Boston College tapes. And it became known around Belfast that some, still living, had talked.

Ricky O'Rawe: Graffiti appeared all over Belfast sayin' Boston College touts.

Scott Pelley: A tout is an informer?

Ricky O'Rawe: Is an informer. It's a very emotive term in Ireland.

Ricky O'Rawe and his wife Bernadette drove us past the threats calling out the Boston touts.

Ricky O'Rawe: It's tantamount to a death sentence.

Scott Pelley: It's tantamount to a death sentence?

Ricky O'Rawe: Absolutely, yeah.

Scott Pelley: When you saw Boston tout you thought they meant you?

Ricky O'Rawe: I knew they meant me!

Why would the O'Rawes run scared 17 years after the shooting stopped? Because despite the Good Friday truce, Belfast is a city torn by ancient hatreds.

These days in the neighborhoods of Belfast, the absence of violence is not exactly peace. The city has really never been more segregated. This is a Protestant neighborhood here. And just across the street is a Catholic community. And have a look at what separates them. They call these peace walls. There are 48 of them. And since the Good Friday Agreement, the walls have been made taller. There are other kinds of walls in Belfast that aren't nearly so visible. The schools, for example. Today, 90 percent of the children here go to a school that is either all Catholic or all Protestant.

Some peace walls run for miles. Many have gates that are sealed at night. On the Catholic side, memorials to the fallen are tended like grudges and memories of martyrs never fade. Over the wall, Protestant neighborhoods are colored by loyalty to Britain. Once a year, in a celebration of a 325-year-old victory over Catholics, Protestants raise enormous towers topped with the likenesses of their enemies -- the flag of the Irish Republic, Catholic politicians, and a symbolic Gerry Adams.

All to be consumed by bitterness that lights Belfast like a city at war.

Bernadette: People grew up with all of this mistrust and maybe hatred towards other communities. You know, what side of the road you stand on waitin' on a bus, "Well, we know that's a Catholic, we know that's a Protestant."

Scott Pelley: I've heard that there's a Catholic cab company and a Protestant cab company.

Bernadette: Absolutely. There's parts of the town that Catholics don't go in to. And there's Protestant people just don't come into Catholic areas. It's the most saddest place.

That sadness, and anger, rose again last year when based on the Boston College tapes, Adams was taken in for questioning in the Jean McConville case. Catholics wanted to see him free. Protestants wanted to see him hang.

Scott Pelley: Was your arrest a dangerous moment for the peace?

Gerry Adams: I think so. To be quite honest, I was sick, sore and tired of a tsunami of stories based upon these tapes linking me to Mrs. McConville's death. So I contacted the police and said, "Look, you want to talk to me, I'm here to talk."

He was held for four days with the Boston College tapes played back to him.

Scott Pelley: They asked you if you were part of the decision to kill Jean McConville.

Gerry Adams: They said that I was a senior member of the IRA at managerial level. So, I'm bound to have known.

Scott Pelley: And you told them what?

Gerry Adams: I told 'em I didn't.

Scott Pelley: The disappearance of Jean McConville was a surprise to you?

Gerry Adams: I didn't know.

Scott Pelley: It was known to the IRA.

Gerry Adams: Yes. Absolutely.

Scott Pelley: And you're saying you didn't know?

Gerry Adams: Yes.

Scott Pelley: How do you orphan 10 children? What kind of depravity is that?

Gerry Adams: That's what happens in wars, Scott. That's not minimize it that's what American soldiers so British soldiers do Irish Republican soldiers do that's what happens in every single conflict.

Scott Pelley: He told us in an interview that he wasn't even aware that she had disappeared for a long time.

Helen McKendry: He likes people to know that. But he's telling lies. He's a liar. I told him to his face, he's a liar. He knows.

Thirty years after she vanished, Jean McConville was discovered on this beach. A hiker found her bones with a bullet hole in the back of her skull.

Scott Pelley: For you, after all these years, what would justice be in your mother's case?

Helen McKendry: I would like to see Gerry Adams stand up and admit that he played a part. I want the people to see what this man really is. He likes to think he's God. He's not. This man has blood on his hands and I want him to pay for what he did.

After days of questioning last year, Adams was released without charges. The police say their investigation continues and they're pursuing all of the Boston College tapes. The university is offering to return the recordings to the participants and Ricky O'Rawe took them up on it.

Scott Pelley: What did you do with the tapes?

Ricky O'Rawe: I burnt 'em.

Scott Pelley: You burned them?

Ricky O'Rawe: Yeah, I lit a big fire, I had a bottle of burgundy, I toasted them when I burnt 'em.

Memories smolder 17 years after that Good Friday -- an exception to the famous Irish warning about forgetting the past. Maybe in Belfast, those who remember history are doomed to repeat it.

Scott Pelley: Do you apologize for all the pain and suffering and injury it was caused?

Gerry Adams: Of course for those civilians, for those people who were caught up in this, who were victims of the IRA, of course I apologize. That I'm a Republican leader, I accept my responsibilities in all of those matters. I don't apologize for the IRA, for its existence, for its right to engage as it did. But surely you wouldn't be a thinking person if you didn't regret all that happened here.