Germany is prosecuting online trolls. Here's how the country is fighting hate speech on the internet.

Dozens of police teams across Germany raided homes before dawn in a coordinated crackdown on a recent Tuesday. The state police weren't looking for drugs or guns, they were looking for people suspected of posting hate speech online.

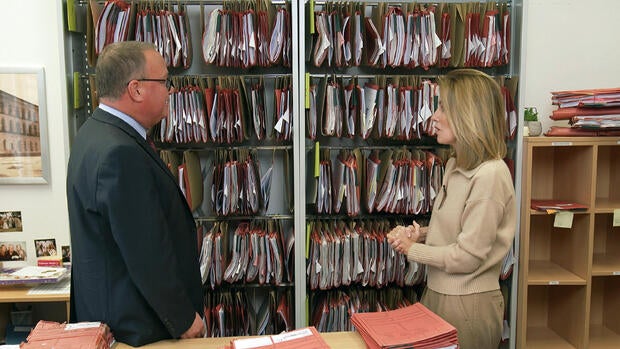

As prosecutors explain it, the German constitution protects free speech, but not hate speech. And here's where it gets tricky: German law prohibits speech that could incite hatred or is deemed insulting. Perpetrators are sometimes surprised to learn that what they post online is illegal, according to Dr. Matthäus Fink, one of the state prosecutors tasked with policing Germany's robust hate speech laws.

"They don't think it was illegal. And they say, 'No, that's my free speech,'" Fink said. "And we say, 'No, you have free speech as well, but it is also has its limits.'"

Germany's laws around speech

In the U.S., most of what gets posted online, even if it's hate-filled, is protected by the First Amendment as free speech. But in Germany, authorities are prosecuting online trolls in an effort to protect discourse and democracy.

It can be a crime to publicly insult someone in Germany, and the punishment can be even worse if the insult is shared online because that content sticks around forever, Fink said.

Fink, and prosecutors Svenja Meininghaus and Frank-Michael Laue, explained that German law prohibits the spread of malicious gossip, violent threats and fake quotes. Reposting lies online can also be a crime.

"The reader can't distinguish whether you just invented this or just reposted it," Meininghaus said. "It's the same for us."

The punishment for breaking hate speech laws can include jail time for repeat offenders. But in most cases, a judge levies a stiff fine and sometimes keeps the offender's devices.

"It's a kind of punishment if you lose your smartphone. It's even worse than the fine you have to pay," Laue said.

The application of Germany's decades-old speech laws were strengthened after its darkest chapter, and then was accelerated online after an assassination of a politician, fueled by the internet, sent shockwaves through the country. In 2015, a video of a local politician named Walter Lübcke went viral after he defended then-Chancellor Angela Merkel's progressive immigration policy.

"People with a very right political world view, they started hating him on the internet. They started insulting him. They started to incite people to kill him. And that went on for about four years," Meininghaus said.

Lübcke was fatally shot in the head four years after he made his speech.

"So that was one of the cases where we see that online hate can sometimes find a way into real life and then hurt people," Meininghaus said.

Investigating and policing speech online

After a man with links to neo-Nazis was arrested in the Lübcke case, Germany ramped up the creation of its online hate task forces. There are 16 units across the country, investigating online hate speech.

Laue, a career criminal prosecutor, leads the Lower Saxony unit, which works on around 3,500 cases a year. Nine investigators work out of the office. They get hundreds of tips a month from police, watchdog groups and victims, Laue said. His unit has successfully prosecuted about 750 hate speech cases over the last four years.

In one case, an online post suggested that refugee children should play in electrical wires, Laue said. The accused had to pay a fine of 3,750 euros.

"It's not a parking ticket," Laue said.

To build their cases, investigators scour social media and use public and government data. Laue says sometimes, social media companies will provide information to prosecutors, but not always. So the task force employs special software investigators to help unmask anonymous users.

Last year, the European Union implemented a new law requiring social media companies to stop the spread of harmful content online in Europe, or face millions of dollars in fines. Some social media companies are not complying with the new law, Josephine Ballon, a CEO of HateAid, a Berlin-based human rights organization that supports the victims of online violence, said.

"I would love social media companies to be a safer place than they are right now. But what we see is that their content moderation is not comprehensive. Sometimes it seems to be working well in some areas, but in many areas, it's just not," Ballon said.

The European Commission, the executive arm of the EU, is currently investigating whether Elon Musk's social media company X has breached the EU digital content law. Musk — who has been criticized for using X to promote Germany's far-right party ahead of national elections — accused the EU of censorship and hating democracy.

Criticism vs. hate speech

It was a 2021 case involving Andy Grote, a local politician, that captured the country's attention. Grote complained about a tweet that called him a "pimmel," a German word for the male anatomy. His complaint triggered a police raid and accusations of excessive censorship by the government.

As prosecutors explained to "60 Minutes" correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi, in Germany it's OK to debate politics online, but it can be a crime to call anyone a pimmel, even a politician.

"Comments like 'You're son of a b—h,' excuse me for using, but these words has nothing to do with a political discussions or a contribution to a discussion," Fink said.

Some worry that by policing the internet, Germany is backsliding into the Germany of 80 years ago, when citizens' words were surveilled. Ballon says there's no surveillance, and that free speech needs boundaries.

"And in the case of Germany, these boundaries are part of our constitution," Ballon said. "Without boundaries, a very small group of people can rely on endless freedom to say anything that they want, while everyone else is scared and intimidated."

Is policing hate speech making a difference?

According to Ballon, about half of internet users in Germany rarely participate in political debates online because they're afraid of being attacked online.

Prosecutors argue they are protecting democracy and discourse by introducing a touch of German order to the unruly internet. The internet extends far beyond Germany's boundaries, but prosecutors there still feel they're making a difference in the battle against hate.

"The option is to say, 'We don't do anything?' No. We are prosecutors," Fink said. "If we see a crime, we want to investigate it. It's a lot of work and there are also borders. It's not an area without law."

In 2015, a meme posted on Facebook falsely implied that Renate Künast, a prominent German politician, had said that every German should learn Turkish.

"And this harms my reputation," Künast said. "Because people say, 'I think she's a bit crazy. Gosh, how can she say that?'"

Künast said she started receiving threats and hate-filled comments from anonymous users online. She'd spent decades in politics, but this was different from anything she'd experienced before.

"The first point was it was much more personal: 'You're looking so ugly. You are an old woman. You, we know where you live.' Or even, 'You should be raped by a group of men so that you see what all these immigrants are doing,'" Künast said.

Künast asked Meta to delete the false quotes attributed to her. She said the company told her it couldn't be done, but Künast sued and won. In a landmark case last year, a German court ruled Meta had to remove all fake quotes attributed to Künast. Meta is appealing.

"This court said, in case of public servants, which have public offices and jobs, it's public interest that their personal rights are protected," Künast said. "Because otherwise no one would go for these jobs, you know? That would harm democracy."