Georgian monks preserve centuries-old winemaking techniques while researchers restore ancient grape varieties

If you want to start a spirited debate at your next holiday meal, ask your guests which country invented wine. France, Italy, or Greece might come to mind.

But most scholars say Georgia - the small former Soviet Republic, is the birthplace of wine. Scientists say wine residue found on pieces of pottery in Georgia dates back 8,000-years.

The country of nearly four million shares a border with Russia and has survived thousands of years of invasions and wars. Multiple dynasties have come and gone. But somehow, many Georgian grapes survived.

Tonight, we'll take you on a journey through Georgia to meet the promoters and protectors of Georgia's ancient vines.

When you first set foot in Georgia's capital Tbilisi... she's hard to miss.

Perched high up over the city, the towering Mother of Georgia wields a sword in her right hand to fend off her enemies and a bowl of wine in her left to welcome friends.

That welcome and the country's deep history of winemaking winds through Georgia. The vines of city dwellers cling to tiny balconies.

Small family vineyards stretch along the countryside and larger producers export millions of bottles globally.

But to fully understand the rich history of wine in Georgia, we went to the fertile River Valley of Kakheti to see the Alaverdi Monastery.

At the foot of the Caucasus Mountains, the monastery looks like a fortress. We were invited inside its walls.

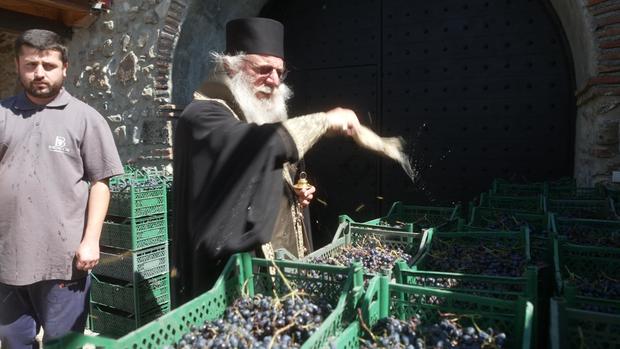

Our host was Georgian Orthodox Bishop David.

He oversees three monks who live on the grounds of the medieval compound. It is a quiet life, committed to god and the godly pursuit of creating a perfect glass of wine.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How many bottles of wine do you make here a year?

Bishop David (translated): 20,000 bottles with a maximum of 50,000 bottles. Our wine cellar's capacity is 30 tons of wine.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Four monks, 20,000 bottles. This is a lot of work. Do they ever sleep?

Bishop David (translated): We sleep, and work at the same time. (laughs)

Locals help work the land. But for centuries, the monks have been the guardians of these ancient vines.

The monastery dates back to the sixth century, Bishop David told us, vines were planted on day one.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Does making wine make you feel closer to God?

Bishop David (translated): Of course. Whenever we are in the vineyard or the wine cellar, we always feel that God is close to us.

Grapes have long held a sacred place in Georgia. In ancient times, wine was considered a divine drink and offered to the gods to win favor.

Georgian soldiers tied a piece of grapevine inside the chest of their uniforms to protect them and to assure that if they died in battle, a vine would sprout from their heart.

Man was mortal, but Georgian vines – eternal.

For centuries the Georgian monks have made wine the same way. Producing reds, whites. and even, "ambers"….more on that in a moment.

The process is uniquely Georgian. Under the monastery, buried six feet deep in the ground, giant clay pots called qvervi are used to ferment, store and age the wine.

It is the traditional way to make wine in Georgia. Many homes have qveris in their cellar. But today there are only a handful of qveri makers who carry on the tradition of hand building these clay beasts. Some hold nearly 900 gallons of wine.

Pressed grapes, skins, stalks and the juice are all mixed into the qveri, which is buried in the ground to maintain a constant temperature.

Every day during the harvest, the monks make their way through the hallowed halls of the monastery to bless the wine cellar, the grapes, and toast the bounty their vineyards bring.

Most of the monk's wine is sold. Some is shared during Sunday communion inside the Alaverdi Cathedral.

On this day, a haunting chant stirred inside the cathedral dome.

The chant, called 'you are the vineyard,' was written 900 years ago by a former king turned monk to honor Georgia's deep connection to its religion and wine.

Lit by candles, it's hard to see the scars of the cathedral. It survived earthquakes and invasions.

In an attempt to erase Georgian culture, Russians whitewashed the cathedral interiors in the 20th century, covering up 11th century frescoes, and used the monastery's qveris to store their gasoline.

But miraculously, many of the vines were unharmed.

Bishop David says today, 100 grape varieties, some dating back 900 year, are still grown on the monastery's grounds.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And how does the wine taste?

Bishop David (translated): Not to talk about taste, it's better to taste it ourselves.

Sitting near the ancient qveris, the bishop opened a bottle.

Bishop David (translated): When tasting the qveri wine for the first time, a person might think they are trying something very different.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Oh it does look golden, amber. Look at that color!

Bishop David (translated): And they say in Georgia that-- "The eye drinks and the eye eats", that's what we have to be thankful to God.

Sharyn Alfonsi: There's much to be thankful to God in this glass.

Bishop David (translated): Of course, it could not be any other way.

Heavenly, with notes of citrus, spices and honey. It is complex, like the history of Georgia, but in a glass.

Georgia's future is also tied to its wines inspiring chefs like Tekuna Gachechiladze.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How much is wine a part of the story of this country?

Chef Tekuna: This is, you know, the question: Wine or food? Or food or wine? You know? It's so together, because we don't imagine our everyday life without the wine. And the wine, it's one of the most important parts in our history, and our culture and in food also.

49-year-old Tekuna wasn't supposed to be a chef. While pursuing a psychology degree in New York, she was working at a restaurant and fell in love with both the chef and cooking.

She dropped the psych degree and the chef, and enrolled in culinary school in Manhattan.

A master chef, Tekuna is now known as the 'godmother' of Georgia's culinary evolution. She runs the popular Café Littera in the capital of Tbilisi – a restaurant known for its adventuresome menu and wine pairings.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You're credited with revolutionizing Georgian cuisine. How have Georgians responded to that?

Chef Tekuna: I just started to experiment. And then I started to-- do new recipes on-- based on the traditional ones, and then give this choice, you know, to people. And in the beginning it was big resistance, the people think you have to keep tradition untouched. But for me, tradition is always innovation, because every dish was somehow innovative when it started.

Georgia sits at the crossroads of Europe and asia. A "Georgian dinner" can look and taste like a trip around the world.

Chef Tekuna: All these influences from-- starting from China, even from America, to the Europe. You know, it's gathered here. It was a hub. And that's why our cuisine, traditional cuisine, it's-- it was always fusion.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Georgia was fusion before fusion was fusion--

Chef Tekuna: Exactly. And also because so many invasions, and we were always under the rule of different countries, and this brought these different tastes, and the spices, and also cooking method.

Chef Tekuna: This is all yours!

Sharyn Alfonsi: Oh gosh, perfect.

Culinary clashes are my favorite kind of conflicts to cover… I reported for duty at the dinner table.

Chef Tekuna: OK?

Sharyn Alfonsi: This is amazing, yes, it's beautiful.

Chef Tekuna: This is our first dish, like appetizer. It's called pkhalis-- vegetables with walnuts. We cook in Georgia lots with the walnuts.

Walnuts are one of the workhorses of Georgian cuisine…pulverized and used the same way the French use butter to make everything creamier.

Not surprisingly, grape leaves are also a favorite ingredient.

Chef Tekuna: This is tolma, and you can't imagine any table without this dish.

Our dinner included five courses with six dishes, each with a different glass of wine.

Chef Tekuna: And then we have this like filet mignon.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you have a couch that I can recline on?

Chef Tekuna: Yes!

Chef Tekuna insisted we taste everything because the wines came from different regions, and each had its own unique flavor.

Chef Tekuna: We have so many great winemakers, you know? It's like a new revolution you know and not losing the old traditions, they improve it and then continue doing the great wines.

But there is no wine more distinctly Georgian than this-

Chef Tekuna: You see the difference?

Sharyn Alfonsi: Look at the color of this!

Chef Tekuna: That's why it's called Amber.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Not orange--

Chef Tekuna: Yeah. No.

Giorgi: Not orange.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Never orange.

Chef Tekuna: No.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Americans know what to do with red wine. We know what to do with white wine. But if you put an amber wine out, I would not know what I should be serving that with.

Chef Tekuna: Actually this is what's very-- interesting,amber wine, it's like a universal wine. You can drink with the vegetables. You can drink with meat. But this is what makes it unique, you know? You can pair almost with everything, you know?

Sharyn Alfonsi: It's versatile. So I noticed you said you don't like to eat when you're cooking, but you'll have a sip right?

Chef Tekuna: But I drink! (laugh)

Sharyn Alfonsi: Fine, then you can stay. (laugh)

Two hours later, the warmth of Georgian hospitality or perhaps all that wine, washed over us.

Chef Tekuna: It's like a Georgian saying that the guests are from the Gods. You have to treat the guests like you treat the Gods.

Sharyn Alfonsi: We usually hear about the guests from hell. From the Gods sounds a lot better.

Chef Tekuna: In Georgia, guests are really from the Gods. Cheers.

When most of us order wine, we look for a favorite variety, consider the region, the age or perhaps the cost. But ordering a glass of wine from Georgia can be a bit more complicated.

The former Soviet Bloc nation is the size of West Virginia but offers more than 40 varieties of wine, each with a tongue twisting name from vines centuries old.

Still, Georgian wine is gaining popularity beyond the country's borders. Last year, nearly a million and a half bottles of it were shipped to the United States – an increase of nearly 30% from the previous year.

We headed to Georgia's wine country to get a taste for ourselves.

Stretched along eastern Georgia… more than 4,000 square miles of vineyards sit at the base of its' mountains like a welcome mat.

This is the Kakheti region. Three quarters of the grapes used to make wine in Georgia are grown here.

In the middle of one of Kakheti's hundreds of vineyards we met an unlikely ambassador of Georgian wine, an American – 47-year-old John Wurderman.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How does an American end up with all of this?

John Wurdeman: Well, it started with a curiosity for a country the more I learned about it, the more fascinating it was. And nobody seemed to know anything about it, at least in my world.

Wurdeman grew up a world away in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was studying art in Russia when he visited neighboring Georgia.

He liked it so much he moved here and in 2006, bought a 62-acre rundown vineyard, hired locals and started Pheasant's Tears Winery.

Georgia is the birthplace of wine. The mild climate and rich soil have made it an ideal place to grow hundreds of varieties of grapes for thousands of years.

At one time, the country, reportedly, had more than 1,400 indigenous grape varieties. Most were wiped out during the Soviet era…when quantity replaced diversity.

John Wurdeman is part of a national effort to recultivate Georgia's ancient vines and bring them back to life.

John Wurdeman: So in Soviet times--out of 525 varieties, you had roughly four or five that were the main ones that were commercially available.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So what happened to the rest?

John Wurdeman: Luckily-- Georgians were still growing them in their back yard. They were allowed to have small, private plots for their own personal use, and they kept the ancestral varieties going. So when we wanted to start to bring back these ancient varieties, together with our friends-- that was where we were going. We were going to the individual back yards of farmers who kept growing the varieties that their grandfathers and great-grandfathers had kept alive.

Clawing back all of the grape varieties is something Georgians take seriously - a kind of declaration of independence from their former Soviet rulers.

In 2014, the Georgian government opened two research centers to locate, study and grow those rare grape vines.

Scientists head into the vineyards once a week to gather critical data. DNA of grape leaves is analyzed, juice is extracted in the field and then tested in labs for disease. Healthy vines are replanted. Today, there are more than 500 native grape varieties growing in Georgia.

At Pheasant's Tears, ancient Georgian methods are used to make the wine. Stems, skins, and juice are all mixed together, then poured in giant qveris buried deep underground and sealed with clay where the mixture ferments and ages.

John Wurdeman: This is our lower qveri level.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is all the wine here made in qveris?

John Wurdeman: Most all of it. There's a couple of wines that will be tasting later that are on the fresher lighter side from western Georgia where we use stainless steel, but everything of structure.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So based on where they are, they have a different taste?

John Wurdeman: Yeah. If they're in a space that breathes versus a reductive space.

The wine typically remains inside the qveris for nine months -

John Wurdeman: This is where we age the wines.

Then it's bottled and stored in a cellar.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So when are these bottles from?

John Wurdeman: These are from the last 15 years. It allows us to understand how the wines develop and what is the most ideal time and for releasing.

Nothing is rushed in Georgia, something we witnessed during lunchtime at the vineyard.

Workers were celebrating the harvest with a traditional Georgian feast called a supra - a lavish meal typically held after weddings, funerals, baptisms and births.

During our lunch, guests broke into song. This is a traditional Georgian folk song…centuries old.

A few guests started dancing. Lunch hour stretched into dinner.

And then came the toasts: a half dozen of them, before dessert.

Sharyn Alfonsi: With so many toasts, so many songs, and dancing, it's amazing anybody eats.

John Wurdeman: Yeah. But the-- the supras last for quite a long time. If workers go out to work for a few hours in the field, and they come back together, they'll have a supra. And they'll have toasts about the things that-- mean the most to them in life.

John Wurdeman: Some people have called the Georgian Supra an "academy" where basically people come together in order to share what they know and to learn from one another.

But John Wurdeman says schooling the rest of the world on Georgian wines hasn't been so easy.

First, there are at least 40 varieties of Georgian wines being served around the world and even the most sophisticated sommelier might struggle to just pronounce them.

Saperavi, rkhatsiteli and mtsvane don't exactly roll off of the tongue.

Then there's the issue of that unusual color - the giant ginger elephant in the glass.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I've noticed a couple people we've spoken to here-- when you say "orange wine," they shudder a little bit and say, "It's amber." Is there any difference?

John Wurdeman: No. In terms of modern wine syntax, they're synonyms. But that was also a little part of the early conversations, where-- when we were talking about "orange wine from Georgia," people worried, "Is this some sort of citrus concoction being sold outside of Atlanta?"

Sharyn Alfonsi: What is it that creates that beautiful color?

John Wurdeman: So you're basically leaving the must or the juice of the grapes with skins, the pips and sometimes the stems. Basically extracting both pigment as well as phenolic structure from the skins. So that's changing the flavor as well as the color. But it's also a lot of our preconceptions can affect how we perceive the wine. Because if you were to show them that same wine in a black glass they might say, " What a delightfully refreshing light red." But when they see it from a white grape they think, " Is this somehow a bit clumsy or rustic or why? You know, this doesn't taste like my Sauvignon Blanc that I'm used to drinking."

Sharyn Alfonsi: A little frustrating?

John Wurdeman: A friend of mine who's a Master of Wine in London, has a beautiful saying that-- she gave at a conference once. She said, "The orange or amber wines of Georgia are not the mean sisters of whites but the introspective cousins of reds."

But over the last decade, the Georgian family of wines - reds, whites and even "ambers," have been embraced around the globe. Last year, Georgia exported over 140 million bottles of wine to more than 65 countries.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What do you attribute to that kind of growth?

John Wurdeman: I think in the very beginning we were walking around with maps and photographs and saying that 'No we're not you know, swarthy versions of Russians.' But, 'Georgians have their own language, their own wine culture, their own culinary culture, history that is very ancient. And you know try the wines.' But it took a fair amount of effort to get people to give us the benefit of the doubt and even to try.

Over the past decade, more than 2,000 new vineyards have taken root in the country and last year, Georgian wine makers made more than $100 million.

John Wurdeman: All of a sudden, it's like watching a black and white picture of a rainbow come to color again. This diversity and expanse of color is coming back to the Georgian table after sleeping for almost-- a few centuries.

For Georgians, it's another reason to celebrate. For the rest of the world, it's a chance to taste history.

Produced by Ashley Velie. Associate producer, Jennifer Dozor. Broadcast associate, Erin DuCharme. Edited by Michael Mongulla.