George Wallace's daughter lives in shadow of past

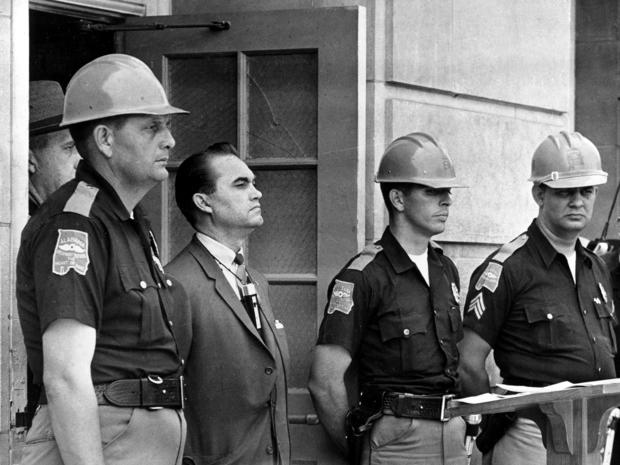

MONTGOMERY, ALA. For 50 years Peggy Wallace Kennedy has lived in the shadow cast by her father, Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, when he stood in a doorway and tried to stop two black students from integrating the University of Alabama.

That single episode in the American civil rights movement - his infamous "stand in the schoolhouse door" - attached an asterisk to her name, she says.

It's a permanent mark she can never erase, despite her own history as a moderate Democrat who gave early support to candidate Barack Obama for president in 2008.

- Daughter of segregationist forges path to tolerance

- The children who marched into civil rights history

- Before Rosa Parks, another woman defied segregation

"If you're George Wallace's daughter, people think the asterisk will always be there. `Oh, your father stood in the schoolhouse door,'" she said in a recent interview. Kennedy was just 13 at the time.

Her mother, Lurleen Wallace, had whisked her away to a lake fishing cabin with her three siblings that day, so they would be nowhere near the wrenching historic drama in which her father played a leading role.

"My mother kept us very, very sheltered, so there were a lot of things we didn't know about," she told "CBS Evening News" in March.

George Wallace, a pragmatic politician and a populist, may or may not have been a true believer in segregation - even though he took office in 1963 with a pledge: "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever."

On June 11, 1963, he stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama's Foster Auditorium to keep Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood from enrolling for classes.

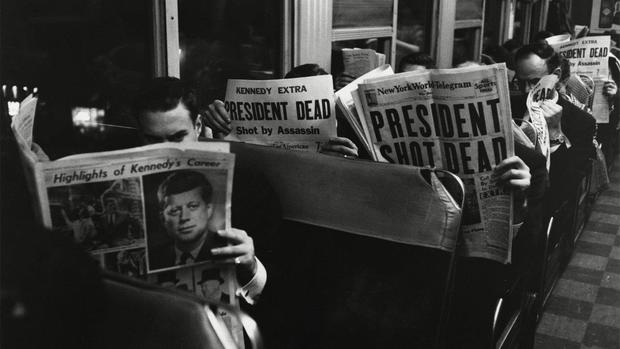

Wallace stepped aside after President John F. Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard.

Jones and Hood enrolled, and Wallace became a national political figure who would run for president the following year.

On the 50th anniversary, all the major players - Wallace, Jones, Hood and Nicholas Katzenbach, the Kennedy administration's representative in Tuscaloosa - are dead.

Wallace died in 1998 after serving four terms as governor, but never once did he discuss the events of June 11, 1963, with his daughter.

Kennedy says his motivations then remain a mystery to her even now.

"He never talked with me about it. I don't even know that he talked with my mother about it. I never heard them have a conversation about the schoolhouse door stand at all," Kennedy said.

Looking back 50 years, Peggy Kennedy recalled that she was a young teenager who was terrified about what might happen to her father amid the tensions and potential violence of the conflict.

And as the years went by, somehow it was just a subject they could not discuss.

"When the subject was broached it was brushed aside," she told an audience last March. She speculates that maybe he was just keeping a political promise, but she can't say for sure.

Culpepper Clark, author of the 1993 book "The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation's Last Stand at the University of Alabama," believes Wallace's daughter is correct in her assumption.

"Wallace clearly bonded with and identified with white voters in Alabama and he kept a promise," Clark said.

Kennedy said her father's actions were difficult for her to understand because her mother, who also became governor, had raised her not to think that she was better than anyone else.

"At that time I just didn't understand why he would just stand and not let two African-Americans enter a university," she said.

But she said the episode marked an irreversible change for the Wallace family.

"That day was kind of the end of our hope for a simple life. It was really the beginning of our living under the shadow of the schoolhouse door for my whole life."

She visited her ailing father frequently in the last years before his death. The conversations were short, due to his health, and he wanted to talk about politics, not the past.

After all, "politics was the family business," she said. But she never found out why he felt he had to stand in the schoolhouse door.

"I definitely regret that," she said.

What Kennedy does know is that her father changed after an assassination attempt during his 1972 presidential campaign.

A bullet fired by Arthur Bremer - whose self-proclaimed intent was to assassinate either Wallace or then-President Richard Nixon - left Wallace paralyzed from the waist down and in constant pain for the rest of his life.

"What it did for him, he realized how much he had made the African-American community suffer, and he realized he needed to be forgiven, genuinely forgiven," she said.

Wallace went to black churches to apologize for his segregationist views and won a fourth term as governor in 1982 with widespread black support.

He honored Jones and Hood and welcomed civil rights leaders like Jesse Jackson into his Montgomery home.

"He was a different man when he passed away. I can assure you of that," Kennedy said.

Kennedy is also a different woman.

For years, she stayed in the background as her husband, lawyer Mark Kennedy, rose through the political ranks to become a justice on the Alabama Supreme Court.

Only after his retirement did she step out of the shadows, first by endorsing Obama in 2008.

She told voters that America still needed healing and "having Barack Obama to lead will give us back our power to heal."

Then in 2009, she attended events in Selma to remember "Bloody Sunday" - the day in 1965 when her father's state troopers attacked voting rights marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In Selma, she introduced U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder - Jones' brother-in-law - and they shared a wish that Jones had lived to see the moment.

Then she marched across the bridge holding hands with U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, who was severely beaten during "Bloody Sunday."

Kennedy said she crossed many bridges in her life, but none as important as that one.

Last March, she joined Lewis and other members of Congress on a civil rights pilgrimage at the University of Alabama, and she walked through the same wood-and-glass doors her father sought to block.

The daughter of the governor who promised "segregation forever" saw a campus with a student body that is almost 13 percent black.

Kennedy, 63, said she has tried in recent years to step out of the shadow of the schoolhouse door and show that families can change.

"Maybe I gave somebody a little bit of hope," she said.