Genetically modified chickens could beat bird flu

In the battle to fight the bird flu virus that has decimated chicken flocks across the Midwest, much of the attention has been on creating a vaccine to protect the poultry.

But in the United Kingdom, researchers are taking a different approach.

They have developed chickens that are genetically modified so they don't spread the bird flu to other chickens with which they are in contact.

The researchers at Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh, and in the University of Cambridge Department of Veterinary Medicine had their first breakthrough in 2011 and have since been working to produce chickens that are resistant to bird flu.

"Chickens are potential bridging hosts that can enable new strains of flu to be transmitted to humans," said Laurence Tiley, a senior lecturer at Cambridge Infectious Diseases, who is one of the researchers working to develop what are called transgenic chickens.

"Preventing virus transmission in chickens should reduce the economic impact of the disease and reduce the risk posed to people exposed to the infected birds," he said. "The genetic modification is a significant first step along the path to developing chickens that are completely resistant to avian flu. These particular birds are only intended for research purposes, not for consumption."

To produce these transgenic chickens, the scientists introduced a new gene that manufactures a "decoy" molecule that mimics an important control element of the bird flu virus. The replication machinery of the virus was tricked into recognizing the decoy molecule instead of the viral genome. This prevents the virus from replicating.

"The decoy mimics an essential part of the flu virus genome that is identical for all strains of influenza A," Tiley said.

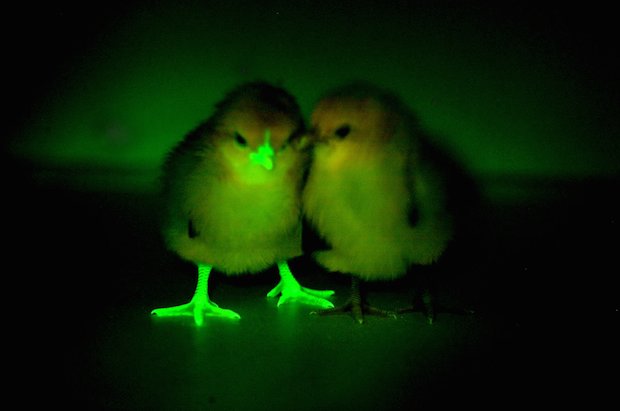

To separate the transgenic chickens from the rest of the flock, researchers injected the birds with a protein that turned them glowing green under ultraviolet light.

"It makes it easy to identify the transgenic birds," Tiley told CBS News. "But clearly if we were going to develop these birds for human production, we wouldn't be trying to persuade people to eat fluorescent, green chickens."

Since their breakthrough in 2011, Tiley along with Cambridge University's Jon Lyall and Roslin Institute's Helen Sang have been making progress towards building resistance in their birds. So far, they have yet to produce a bird with complete resistance - a crucial step that would ensure a flock wouldn't get sick.

"If you have birds that can still become infected but don't pass the infection on, the virus is replicating in those birds," Tiley said. "There is a possibly the virus can evolve within those birds and overcome whatever the defect is that it is suffering. It's better from a longevity strategy to be able to prevent the initial infection in the first place."

Chicken breeders have offered some support for the research, though Tiley said the industry as a whole appears skittish about being too closely associated with transgenic chickens.

"I think the industry's attitude is that they are cautious," he said, over concerns about coming under attack from anti-GMO activists.

"They are very keen to point out that they are not developing transgenic birds for human consumption," he said. "They are just interested in the potential of GM technology for introducing disease resistance for birds."

Tiley said their work currently receives some funding from one of the world's top chicken breeders, Germany's EW Group. Arkansas-based Cobb-Vantress, owned by top U.S. chicken company Tyson Foods Inc., had supported their earlier work.

The company told Reuters that it had stopped research into GMO chickens because there was no approved commercial use.

Tiley said he expected it would still be about a decade before he could envision their birds making it onto supermarket shelves. Hopefully by then, the opposition to GMO would have softened, he said.

"That is a bridge we are going to have to cross in the future in terms of persuading the public that this something they are going to be interested in," he said. "Disease resistance is something that may become more publicly acceptable. It is easier to justify doing this than increasing productivity or making something resistant to a herbicide."

Until then, vaccines are the most promising alternative.

A vaccine is being developed to target the H5N2 virus that has killed 48 million birds since early March in 15 states, including hardest-hit Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska. It is one aspect of planning for a potential recurrence of the bird flu, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack told a House hearing in July.

Scientists believe the virus was spread through the droppings of wild birds migrating north to nesting grounds. They're concerned it could return this fall when birds fly south for the winter or again next spring.

But vaccines aren't without problems.

Many countries have a strict policy of refusing to accept meat from nations using a vaccine because it can be difficult to discern through testing whether birds were infected with an active virus or were vaccinated, said James Sumner, president of the USA Poultry & Egg Export Council.