Medical Middlemen: Broken system making it harder for hospitals and patients to get some life-saving drugs

American hospitals have been living with serious drug shortages for more than a decade. Most days, nearly 300 essential drugs can be in short supply. After months of investigation, we found it's not a matter of supply and demand, the drugs are needed and the ingredients are easy to make, it's that pharmaceutical companies have stopped producing many life-saving generic drugs because they make too little profit. Yet, year after year, the government stays on the sidelines as companies take drug production offline - and doctors worry the shortages are compromising patient care.

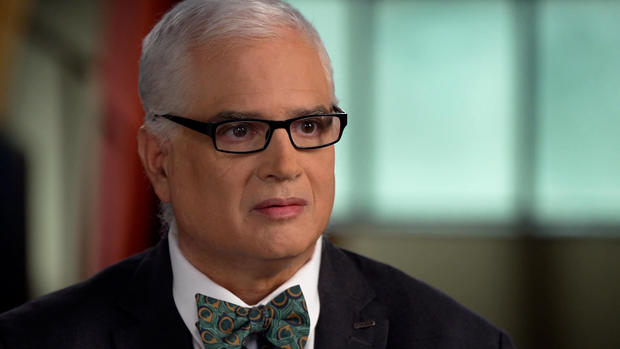

Neonatologist Dr. Mitch Goldstein treats the most vulnerable patients at Loma Linda University Children's Hospital in California.

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: Most of these babies would fit comfortably in the palm of your hand.

Bill Whitaker: Struggling to hold on to life?

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: They really are.

Many of these premature and sick babies have undeveloped digestive systems, so Dr. Goldstein keeps them alive with intravenous nutrients, many of which are in short supply.

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: It can be certain minerals. It could be certain salts. Things that you would ordinarily find in a college chemistry lab, we can't get

Bill Whitaker: But these are basic.

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: These are basic things. Glucose. Sugar. It's not hard to make. But the point is we can't get it.

Bill Whitaker: So then what are your options?

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: You don't have any. You do the best you can.

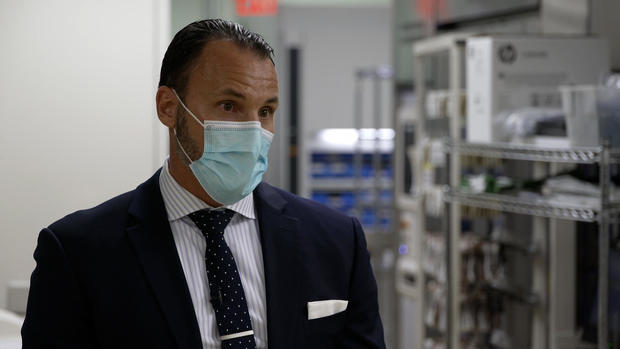

Antony Gobin heads the pharmacy at Loma Linda Hospital. He told us shortages of basic drugs are a constant worry.

Bill Whitaker: Help me understand. How often do you face drug shortages?

Antony Gobin: Every day.

Bill Whitaker: Is this just another casualty of COVID?

Antony Gobin: No. So we were dealing with shortages long before COVID. They're all very old, fundamental drugs that every hospital in the country needs and uses.

Drug shortages can kill. In 2011, when norepinephrine, an old, low profit drug used to treat septic shock, was in short supply, hundreds of people around the country died.

Just about every hospital in the U.S. has weekly drug shortage meetings like this one at Loma Linda.

Antony Gobin in meeting: Dextrose?

Pharmacist in meeting: Dextrose vials-- still completely out of the vials. We are using these syringes for everything.

During a drug shortage, hospitals may be forced to switch patients to less safe or effective alternative drugs. They retrieve leftovers from single dose drug vials to share with other patients and avoid wasting a single drop.

Antony Gobin in meeting: Ask the pharmacist [about] maybe further concentrating to try to conserve some of these 100-ML bags.

Antony Gobin: You would think to yourself, "How hard is it to manufacture some of these simple meds, like dextrose or sterile water?" But, some of these are low-margin drugs. And because of that smaller margin, you don't have a ton of manufacturers making the product.

Sarah Carney and Cyndi Valenta were facing the same wrenching ordeal at Loma Linda Hospital: both had children undergoing chemotherapy for aggressive leukemia.

Sarah's son, Mikah, was in pre-kindergarten when he began the painful treatment.

Sarah Carney: Um, he wasn't the same kid. Several times he looked at us and said, "Why is this happening to me? What did I do wrong?"

Cyndi Valenta: So much is being thrown at you, new-- back then I didn't understand. I thought there was one type of chemo that people took when they had cancer. I didn't realize there was this whole road map, um—this regimen we had to follow.

Bill Whitaker: They give you a schedule and they tell you you must stick to that schedule.

Cyndi Valenta: Every function of your life went on this road map. So if -- chemo was supposed to be given on day one and day five, whether that was a holiday or not...we had to take john in to get his infusions.

Cyndi's 13-year-old son, John, gave up baseball to beat his leukemia. In late 2019, he settled in to his usual chemo chair and got some bad news: the chemo drug vincristine he'd been using for more than two years was suddenly unavailable.

Bill Whitaker: This was after the doctors had insisted with you that you keep to this schedule.

Cyndi Valenta: Uh-huh

Bill Whitaker: What was John's reaction?

Cyndi Valenta: Scared.

Vincristine, an essential drug for childhood leukemia, was in short supply nationwide. It's a chief ingredient of a chemo cocktail that has an 80% to 90% cure rate. When Sarah learned Mikah wouldn't get his treatment, she was on the phone for days calling anyone who might know how to get the life-saving drug: other cancer moms, the hospital, Pfizer, the drug maker.

Sarah Carney: I honestly didn't even know who to believe. Because the pharmaceutical company is telling me they have it. And the hospital is telling me, "We've-- we call them every day and they are telling us they don't have it." So, I didn't know what to say.

Cyndi Valenta: As a cancer mom, we shouldn't be fighting for our children to get a drug that is needed. You know? We are fighting every day to keep their spirits up, to change our whole life to make sure that they're getting this treatment. There's no other alternative, it's just a gut-wrenching feeling of just fear and anger.

Sarah and Cyndi raised all kinds of alarms on social media. A week later, drug maker Pfizer shipped scarce doses of vincristine to Loma Linda, enough for Mikah and John to continue their treatments.

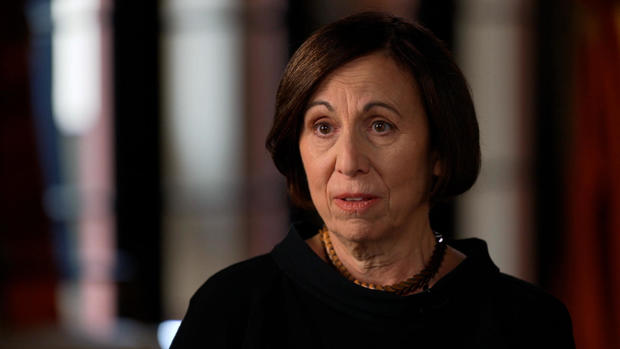

Milwaulkee pedatric oncologist Cindy Schwartz is a committee chair of the Children's Oncology Group, a consortium of cancer researchers and bioethicists from across the country.

Dr. Cindy Schwartz: These recent shortages have become very, very serious and really hit drugs like vincristine, that are in every regimen.

Vincristine was one of 16 chemo drugs in short supply last year. Dr. Schwartz told us the shortages are forcing doctors to ration scarce drugs.

Bill Whitaker: Does that present you with some ethical dilemmas?

Dr. Cindy Schwartz: Of course it does. Who wants to be picking how you prioritize one person over another?

Bill Whitaker: One child over another—

Dr. Cindy Schwartz: One child over another.

Bill Whitaker: I'm just trying to come up with some explanation for why a drug that is known to save lives is not valued, why it's--

Dr. Cindy Schwartz: It should be a top value.

Unlike newer brand name drugs that cost as much as six figures per dose, vincristine, a low margin "generic" drug around since the 1960s, costs about $5 per dose. Months before the shortage, one of the two remaining vincristine manufacturers, Teva Pharmaceuticals, announced it would stop making vincristine for U.S. hospitals.

Ross Day: They indicated that it was a business decision. They could make more money on more profitable drugs-- than Vincristine.

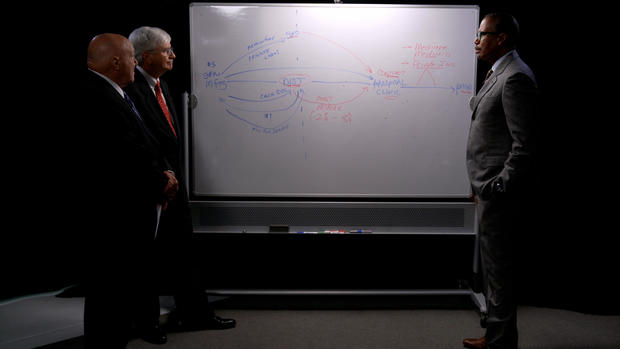

Ross Day is a former director of Vizient, the country's largest group purchasing organization, or GPO - a health services company that negotiates contracts between hospitals, drug makers and medical suppliers.

Ross Day: I don't understand why companies in good conscience can make those kinds of decisions. None of these companies are poor companies. They have the opportunity to not make as much on one drug and still make plenty of margin and profit on other drugs.

Bill Simmons: Those kinds of economic decisions are made not because that that person running that business is malicious in their intent, they're trying to keep that plant operating.

We also met with Bill Simmons, a former high-ranking generic drug executive.

Bill Simmons: Y-- you have to keep in mind that-- corporations aren't charities.

The two former executives once negotiated drug contracts across the table from one another. They still have disagreements.

We asked them to spell out the economics of generic drug shortages — from the manufacturers to the hospitals and patients.

We were hoping a diagram would help.

Bill Simmons: There's a gatekeeper here. I'm putting "GPO" in. It's called a Group Purchasing Organization, and that organization negotiates prices for the hospital collectively in an effort to get lower pricing on products.

At least that's the way it's supposed to work.

Bill Simmons: And you got money going this way, they pay it, and then they sell it to the hospital, and then it comes back this way.

Ross Day: The Contract Price.

Bill Simmons: A concept of fee for service.

Ross Day: A Cost Minus.

Bill Whitaker: Why is all of that part of the process?

Bill Simmons: The honest answer to that is, this private label, fee-for-service, cost-minus: These are things to create lack of transparency to pricing.

Bill Whitaker: But, this confusion is on purpose?

Bill Simmons: Yeah. I want to charge different prices, and not have clarity around what people are really paying.

Bill Whitaker: So far, this is clear as mud.

Ross Day: But I'm not sure there are more efficient ways to administer the supply chain, at least I've not been presented one.

Bill Whitaker: There's nothing more efficient than this?

But all the arrows and acronyms point to one thing: a broken system, which our investigation found is a root cause of drug shortages. Take the $5 cancer drug vincristine. The middlemen, the group purchasing organizations and drug distributors take their cut for administrative, marketing and other fees and hospital incentives. The drug manufacturers end up with just a small fraction of what the patient pays. Many have simply stopped making the least profitable drugs.

Bill Simmons: We are systematically shutting down all of our U.S. manufacturing because we do not pay enough money for the drugs to the manufacturers, and not enough money is paid because of the middlemen.

Bill Whitaker: I guarantee you there'd be patients over here who would say, "I would pay more if I could be guaranteed I would get these drugs when I need them."

Bill Simmons: Bill, I think, this person over here might be willing to pay another 20 bucks. but these people will-- will absorb a lotta that $20 before it gets over here.

Group purchasing organizations control more than $250 billion in hospital purchases annually. The biggest three account for about 90% of the business. They typically award the contract to the manufacturer with the lowest price drug. Add in all the complex fees and the group purchasing organizations grow wealthier, while losing manufacturers are squeezed out.

Bill Simmons: If you refuse to sell through a group purchasing organization, or through drug wholesalers, you will not exist.

Bill Whitaker: You're out?

Bill Simmons: You are out.

Ross Day: It's not a GPO's best interest at all, to drive anybody out of the market. I've attributed more of the drug shortage problem to some decisions by FDA to start evaluating manufacturers differently than they had in the past.

The FDA, to improve patient safety, raised the bar on quality controls at drug plants. Several were shut down.

Bill Simmons: The FDA wants higher quality products that cost more money to make, and the GPOs want to drive the price down to whoever will supply 'em the lowest price, which is usually people who are not investing in equipment, not investing in quality, and those two things don't go together.

In July 2019, when Teva Pharmaceuticals stopped making vincristine for lack of profit, Pfizer's generic division, Hospira, became the sole supplier. In a letter to the FDA we obtained, Pfizer called the situation untenable. Two months later, a quality control issue forced Pfizer to suspend production for six weeks, which is not uncommon in drug manufacturing.

Bill Whitaker: When you're down to just a couple of manufacturers, and one is found to have quality control problems--

Bill Simmons: Yeah.

Bill Whitaker: Where do you go? There's no Plan B?

Bill Simmons: There is no Plan B.

40% of generic drugs now have just one manufacturer.

Ross Day: I think the government could play a role in keeping some of these drug manufacturers viable because this is just as much of an emergency in my mind as the pandemic is. But I'm not ready to say the current model is ready to blow up. Maybe tweak.

Back at Loma Linda...

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: I think about the babies I take care of.

...Dr. Mitch Goldstein, like doctors all across the country, is bracing for more shortages.

Dr. Mitch Goldstein: It's horrible. And it's like being in a siege and you're, you're running out of ammunition. Sometimes we look at it and it's just, "How are we gonna survive this next day? The day after? And what is the new problem? What's on the horizon? What's gonna happen next week?"

Produced by Sam Hornblower. Associate producer, Mabel Kabani. Broadcast associate, Emilio Almonte. Edited by Jorge J. García.