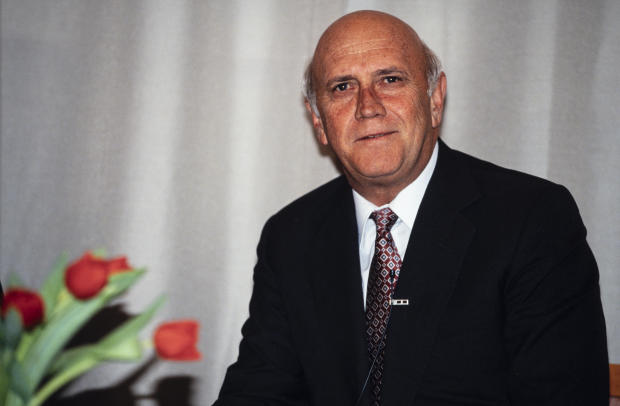

FW de Klerk, South Africa's last apartheid president, has died at 85

Johannesburg — Frederik Willem de Klerk, South Africa's last white minority president who ruled over the final years of apartheid's demise between 1989 and 1994, has died. In a statement released on Thursday, his foundation announced with "the deepest sadness" that de Klerk had "died peacefully at his home" following a long battle with cancer.

FW de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 with the man who would succeed him, South Africa's first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, "for their work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa."

De Klerk released Mandela from prison in 1990, after the pro-democracy icon had served 27 years behind bars. As leader of the then-National Party, whose official policy was one of racial segregation, De Klerk initiated broad reforms, including the unbanning of liberation movements like Mandela's African National Congress, the release of other political leaders from prison, and the start of negotiations for a transition to democracy.

Throughout his career De Klerk had vehemently defended apartheid, the country's system of racial segregation, but after becoming president he stunned not only his country but the entire world by reconsidering the racist policies. He had hoped to preserve elements of the white political order while loosening the reins of repression, but in releasing Mandela from jail, he also unleashed a process that, ultimately, he could not control, and which led to the peaceful dismantling of the racist regime.

Despite sharing the Peace Prize with Mandela, the two men were bitter opponents during the tough negotiations for a new democratic South Africa, as De Klerk was fiercely opposed to a winner takes all solution.

"Don't expect me to negotiate myself out of power," he told Western diplomats. But he ended up doing just that.

De Klerk's legacy remains marred by controversy: He has long been accused by various groups of instigating violence as the head of state during the final days of apartheid. He was accused specifically of instigating violence between Mandela's ANC and the Inkatha Freedom Front. The clashes, which left scores dead in the run-up to the country's first democratic elections, were later found to have been fueled by a white, third-party force.

In his autobiography, De Klerk wrote about his first meeting with Mandela, saying: "During most of the meeting each of us cautiously sized up the other. The first impressions that he conveyed were of dignity, courtesy and self-confidence. He also had the ability to radiate unusual warmth and charm — when he so chose."

At one point during South Africa's negotiations for a new constitution, Mandela denounced De Klerk as "the head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime."

When those negotiations adjourned for Christmas, Mandela shook De Klerk's hand goodbye. But De Klerk wrote in his book that he had " accepted Mandela's gesture as gracefully as I could. But Mandela's vicious and unwarranted attack created a rift between us that never again fully healed."

For years De Klerk defended apartheid as "an honorable vision of justice" that had simply, over time, become no longer viable, instead of recognizing it as a brutal system that denied black South Africans the most basic of human rights. But in 1996, at the country's Truth and Reconciliation commission, he apologized for the pain and suffering the regime had caused.

He continued to maintain until his death, however, that he had a clear conscience and was not guilty of any crime.