Full transcript of "Face the Nation" on July 18, 2021

On this week's "Face the Nation," moderated by John Dickerson:

- Ken McClure — Springfield Missouri Mayor

- Dr. Scott Gottlieb — Former FDA commissioner

- Admiral Mike Mullen — Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Jill Schlesinger — CBS News business analyst

- Chris Krebs — Former CISA director

- David Becker — Founder and director of the Center For Election Innovation and Research

Click here to browse full transcripts of "Face the Nation."

JOHN DICKERSON: I'm John Dickerson in Washington. And this week on FACE THE NATION, with scientists now warning that if you are unvaccinated, you will likely get the coronavirus, will that change the minds of the biggest holdouts when it comes to getting vaccinated? America is seeing a summer surge of COVID. Case rates have more than doubled since late June, fueled by the highly contagious Delta variant.

DR. GRANT COLFAX: The Delta variant is COVID on steroids. This virus is far more infectious than the COVID we were dealing with a year ago.

JOHN DICKERSON: According to the CDC, this surge was avoidable. Hotspots are mostly states or regions with low vaccine rates. In Springfield, Missouri, cases are up one hundred and fifty percent since last month. We'll talk with the city's mayor, Ken McClure. And we'll check in with former FDA Commissioner Doctor Scott Gottlieb. In their campaign to get more people vaccinated, the Biden administration targets COVID-19 social media misinformation.

MAN: What's your message to platforms like Facebook?

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN: Look, the only pandemic we have is among the unvaccinated. And that's-- and they're-- and they're killing people.

JOHN DICKERSON: What can be done to fight misinformation? We'll ask the former head of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Chris Krebs. Elections expert, David Becker, will weigh in on challenges across the country to voting laws. And CBS News business analyst Jill Schlesinger will tell us why prices are rising, and if and when we should expect to see them return to normal. Plus, context on some of the jaw-dropping revelations from new books about the Trump presidency. With former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Michael Mullen.

It's all just ahead on FACE THE NATION.

Good morning, and welcome to FACE THE NATION. Many weeks when we put together this broadcast, we're challenged by the number of stories that we want to cover and how best to illuminate them. This is one of those weeks. We're going to try to get to a lot today. Our lead is clear, though, it's a story that has dominated the news for eighteen months now, with a dangerous new twist, causing a surge of the coronavirus here in the U.S. Mark Strassmann reports from Van Horn, Texas.

(Begin VT)

MARK STRASSMANN (CBS News Senior National Correspondent): COVID has boomeranged. The menace, the masking, the fear, all back. And it's largely a self-inflicted wound across our two Americas.

DR. ROCHELLE WALENSKY: This is becoming a pandemic of the unvaccinated.

MARK STRASSMANN: As of midnight, Los Angeles reimposed its indoor mask mandate. Las Vegas wants safer odds, now recommending masks in casinos and all indoor spaces. For the first time since January, new weekly COVID cases have jumped in all fifty states, fueled by the Delta variant. Nationally, a spike of almost seventy percent. Hospitalizations up roughly thirty-six percent. Deaths, twenty-six percent. But in the same week, nationally new vaccination doses plummeted another thirty-five percent.

Immunologists say these dots are easy to connect. Take Texas, in the bottom twenty states for its vaccination rate. Week to week, new cases here soared more than one hundred percent.

Or consider the sickest COVID patients, the ones in hospitals. Nationwide, ninety-seven percent of them are unvaccinated.

WOMAN: Let's get rid of the vaccine.

MARK STRASSMANN: Especially galling to scientists, the relentless campaign of distrust and disinformation against the vaccines. COVID patients are getting younger, more children in the ICU. Florida's rate of new COVID cases four times the national average. Governor Ron DeSantis encourages vaccinations but hawks merchandise online that's anti-Fauci and anti-masking, messaging that resonates with millions of Americans.

MAN #1: I'm just done. I'm not-- I've-- I'm vaccinated. I don't need to wear a mask.

MARK STRASSMANN: Infections surges in places like Tennessee in the bottom five for vaccinating adults. Eighty percent of children here between twelve and fifteen are also unvaccinated. But the state has stopped all vaccine outreach to adolescents.

MAN #2: We've got to get folks back into their pediatrician, back into their doctor, and really ensure that they have adequate access to vaccinations and adequate education.

(End VT)

JOHN DICKERSON: That's Mark Strassmann in Van Horn, Texas.

We go now to Ken McClure, the mayor of Springfield, Missouri, where cases have skyrocketed, driven by the spread of the Delta variant. Good morning, Mister Mayor.

KEN MCCLURE (Mayor of Springfield): Good morning, thank you for having me.

JOHN DICKERSON: In your community, the two largest hospitals are maxed out. One of them, the-- the CEO of the hospital tweeted that he was pleading with people so that nurses would have to stop zipping body bags. How did it come to this?

KEN MCCLURE: I think there are several reasons. First, Springfield is a hub. We are an attraction for tourism, we are an attraction for transportation, for business, for higher education and certainly health care. So, people come to Springfield to shop, to do business. And so, people will come here. And I think that has greatly increased our exposure, compounded with what has been already indicated on misinformation.

JOHN DICKERSON: What kinds of misinformation are you seeing in your community?

KEN MCCLURE: I think we are seeing a lot spread through social media as people are talking about fears which they have, health-related fears, what it might do to them later on in their lives, what might be contained in the vaccinations. And that information is just incorrect. And I think we as a society and certainly in our community are being hurt by it.

JOHN DICKERSON: There's been a conversation throughout this pandemic about information that comes from the top down and information that comes in the community, which is why we wanted to talk to you. What is the most effective work that's going on there on the ground to address those who are vaccine hesitant?

KEN MCCLURE: We are a community of collaboration. Nothing really of substance gets done in Springfield without a lot of people talking about it. And so, we're focusing on those trusted community leaders, those trusted community institutions. And we know that if it comes from the community and leaders of people trust that helps. The Springfield News-Leader this morning had a great article, focusing on several community leaders who had taken the vaccine, why they were encouraging it. So, we are working with so many entities to try to spread the word. And these are trusted sources. And I think that's a key to what we have to do to overcome this.

JOHN DICKERSON: How about in the churches? The pastors-- there's been-- pastors have been talking about it, haven't they?

KEN MCCLURE: The pastors have been a great help through this. We had established in April a year ago what we call the Have Faith Initiative, which at its peak had eighty to one hundred different churches across denominational lines. We've had several of our largest churches, including the pastors in the last week or ten days, stepping up from the pulpit and urging that their congregations get vaccinated. Churches have been stepping up to host vaccination clinics, and the key is faith leaders are trusted. People respect those who-- with whom they worship, their worship leaders. And so we are relying upon those trusted entities. And it's-- we had just this past week, for example, the latest numbers showing that we had the largest increase in our vaccination rate in several weeks. And so I am optimistic that that message is starting to take-- take hold right now.

JOHN DICKERSON: How about-- there's another somewhat mildly controversial issue about going door to door to get the information to people who may not get this kind of accurate information you were talking about? How-- how has that worked in your community?

KEN MCCLURE: Well, I think the whole discussion and going door to door has been overblown, I will tell you that public health has been using the door to-- going door-to-door philosophy for years. It has been a tried-and-true practice which they use. Our Springfield-Greene County Public Health Department is using it, has been using it for a long time. But the key is that these are trusted community people. We call them community advocates. So, it gets down to the people that community members will trust, the spreading information that is factual and trustworthy.

JOHN DICKERSON: And how has the community in-- in the past, there have been instances where a community faced with a challenge like this unifies. But we've seen so much disunity in America on some of these questions related to the coronavirus. How has the reaction been in this most recent wave, as you've seen the Delta variant come through Springfield?

KEN MCCLURE: The most recent wave, in my opinion, has been very positive because we're talking about community collaboration and that, ultimately, is going to be the key to our success. We know what the solution is. It's vaccination. People need to get it. It's readily available. We have so many sites that can ser-- provide that service. The age groups are now all encompassing down to age twelve. So it gets down to the community leaders, the community institutions that people trust, saying you have to get vaccination. That's the only way that we are going to emerge from this.

JOHN DICKERSON: You mentioned the school. Springfield is the home to the-- to the largest school district in the state as I understand it. Mass mandates have come back for the summer. What do you think about mandatory vaccinations for the fall when they go back to school?

KEN MCCLURE: Well, mandatory vaccinations are going to be a very, very touchy issues, particularly, as you get into publicly funded institutions. Some private institutions are doing that. I know our school district is strongly encouraging that vaccinations occur. They'll be doing that, I think, as students come back in the fall and to urge their parents to do that. But I have every confidence that the Springfield Public School District will take the appropriate steps to make sure students are as safe as can be. I know they want to focus on in-person learning and I believe that they'll be able to do that.

JOHN DICKERSON: A number of other counties in Missouri have low vaccination rates. What would you advise the mayors and leaders in those counties who haven't yet experienced what you're going through? What would your message to them be?

KEN MCCLURE: My message is that the surge is coming. The Delta variant will be there. It's going to spread. It's already spreading throughout Missouri. Take advantage of this time to get your vaccination rates up as high as you can. Use your community collaboration, your trusted sources, make sure that people have good information, solid information, and use that time wisely because it will be too late if you have not established those relationships by the time that it gets there. But the surge will spread. And so, hopefully, people can learn what we've been experiencing here in Springfield.

JOHN DICKERSON: Mayor Ken McClure, we thank you very much for being with us this morning. Good luck in your community. Thanks again.

KEN MCCLURE: Thank you.

JOHN DICKERSON: And we go now to former FDA Commissioner Doctor Scott Gottlieb, who is on the board of Pfizer and joins us from Westport, Connecticut. Good morning, Doctor Gottlieb.

SCOTT GOTTLIEB, M.D. (Former FDA Commisisoner/@ScottGottliebMD): Good morning.

JOHN DICKERSON: So the CDC director said this week that the-- that there is an epidemic of the unvaccinated. What's your reaction to that?

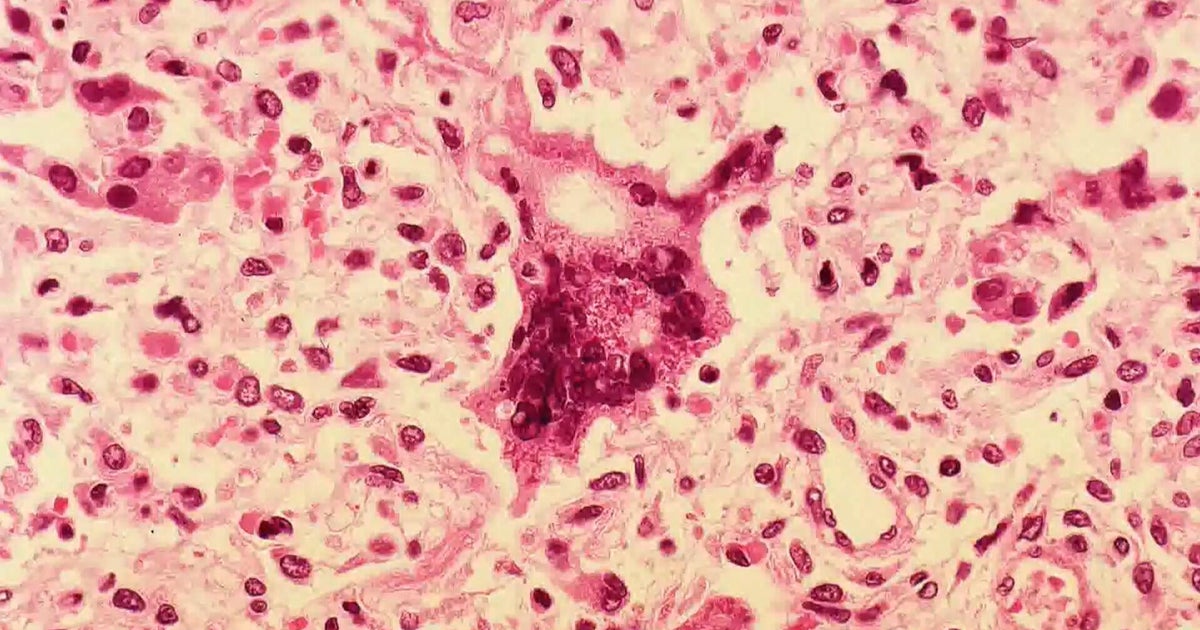

SCOTT GOTTLIEB: Well, look, when you look at the people who have been hospitalized, ninety-seven percent of the hospitalizations are in people who are unvaccinated and most of the deaths that are occurring right now are in people who are unvaccinated. The bottom line is that many people are no longer susceptible to COVID, more than fifty percent, about fifty percent of the population has been fully vaccinated. Probably another third of the American population has been previously infected with this virus. So many people aren't susceptible to the virus. But if twenty-five percent of the population remains susceptible to the virus, in absolute terms, that's still a lot of people. And this virus is so contagious, this variant is so contagious that it's going to infect the majority that most people will either get vaccinated or have been previously infected or they will get this Delta variant. And for most people who get this Delta variant, it's going to be the most serious virus that they get in their lifetime in terms of the risk of putting them in the hospital.

JOHN DICKERSON: We just talked to the mayor there of Springfield, Missouri, who said it was-- sent a message to other communities--it's coming. Do we-- it just reminds me of the original days of this pandemic where the numbers kind of caught up to where reality was. Is-- do we have a handle really on the Delta variant and how it's spreading and how much of it there is in the community.

SCOTT GOTTLIEB: Well, we're seeing a decoupling between cases and hospitalizations and deaths, and I think that's likely to persist, England is seeing that as well, and they're-- they're further ahead in terms of their Delta epidemic than us. And that's because more of the vulnerable population has been vaccinated. I think, at this point, we're probably undercounting how many infections are in the United States right now, because to the extent that a lot of the infections are occurring in younger and healthier people who might be getting mild illness, they're not-- probably not presenting to get tested. And to extent that there are some breakthrough cases either asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases in those who have been vaccinated, they're not presenting to get tested because, if you've been vaccinated, you don't think that you have the coronavirus, even if you develop a mild illness. And we're not doing a lot of routine screening right now. Unless you work for the New York Yankees you're not getting tested on a regular basis. So, I think that this Delta wave could be far more advanced than what we're detecting right now in our ascertainment. The number of cases we're actually picking up could be lower. At the peak of the epidemic, in the wintertime, we were probably turning over one in three or one in four infections. In the summer wave of last summer, we were probably picking up more like one in ten infections. We might be picking up something on the order of one in ten or one in twenty infections right now because more of those infections are occurring in people who either won't present for testing or they're mild infections and they're self-limiting. So, the people who tend to be getting tested right now are people who are getting very sick or people who are developing tell-tale symptoms of COVID like loss of taste or smell. And that's only about fifteen or twenty percent of people who will become infected.

JOHN DICKERSON: So, if there's low ascertainment, if we don't really know as much that's in the community as is actually there. And you live in a low-vaccinated community that doesn't yet have the headlines about hospitals filling, is that a fair expectation that you're going to start seeing those headlines in some number of days?

SCOTT GOTTLIEB.: It depends on where you live, I think if you live in states like I'm in right now where vaccination rates are very high and there's been a lot of previous spread, there is a wall of immunity. And I think it's going to be a backstop against Delta spread. If you're in parts of the country where vaccination rates are low and there hasn't been a lot of virus spread and that's a lot of parts of the rural south. I think it's much more vulnerable. I think people who live in those communities, especially if you live in communities where the prevalence is already high, I think it's prudent to take precautions if you're a vulnerable individual. And Delta is so contagious that when we talk about masks, I don't think we should just talk about masks. I think we should be talking about high-quality mask. Quality of mask is going to make a difference with a variant that spreads more aggressively like Delta does, where people are more contagious and exude more virus and trying to get in N95 masks into the hands of vulnerable individuals in places where this is really epidemic, I think is going to be important. Even in cases where they're vaccinated, if they want to add another layer of protection, there are a supply of N95 masks right now. There is no shortage. There's plenty of masks available for health care workers. So it could be something that we start talking about getting better quality masks into the hands of people, because I think it's going to be hard to mandate these things right now. But we can certainly provide them so people can use them on a voluntary basis to try to protect themselves.

JOHN DICKERSON: Let me just underscore that briefly, because one of the things we have seen is in people who don't want to get vaccinated, they say, well, I'll wear a mask. But your point is if you're going to wear a mask, any old piece of cloth isn't going to do. You have to have an N95 or something that's truly robust.

SCOTT GOTTLIEB: Right, remember, the original discussion around masks was that if we put masks on everyone, people who are asymptomatic and likely to transmit the infection would be less likely to transmit the infection if they had a cloth mask on or even a procedure mask on. And there is data to suggest that. There's data in flu and there's now data in COVID. But if you want to actually derive protection from the mask, meaning you want to protect yourself from others spreading the virus to you. Quality of mask does matter and a-- and a high-quality N95 mask is going to afford you a much better level of protection, especially if you fit it and wear it properly. So, quality of mask is important. And I think if you're a vulnerable individual who wants to use that mask to protect yourself and not just use that mask to cut down on the risk that you could be a super spreader, you could be spreading the virus to others, then you have to look out for a high-quality mask. They are available. Remember, originally during the epidemic, people were reluctant to recommend masks because there was a shortage for health care workers. There's now plenty of masks. The administration has done a good job getting masks out into the marketplace so you can get them from reputable suppliers like 3M right now.

JOHN DICKERSON: Let me ask you about misinformation. From a medical perspective what are the one or two things that are out there that are the biggest sources of misinformation, in your view?

SCOTT GOTTLIEB: Probably the most pervasive is that somehow the vaccine itself is going to have an impact on fertility. I think that that's discouraging a lot of young women from getting vaccinated. I think quite the opposite is true. What we've seen is COVID infection during pregnancy can be very dangerous. I think every woman who's an expectant mom or a prospective mom should be talking to their doctor about getting vaccinated. The CDC has now started a registry called v-safe. You can go on and look at it right now where they've a one hundred and thirty-three thousand women who've registered for this registry who became pregnant after they got vaccinated-- they got vaccinated, while they were pregnant. And so, they are prospectively collecting data on the safety of the vaccine in pregnancy, and it looks very encouraging. Pfizer, the company I'm on the board of, is also doing a study of the vaccine in pregnancy. So, I think this is the single biggest piece of misinformation out there to discourage use of the vaccine. The other one is that this is somehow a DNA vaccine. It's going to integrate into your genome. That's not the case. This is an mRNA vaccine. And what it really is doing is delivering a genetic sequence of mRNA of the-- of the spike protein. So, basically, the sequence that codes for production of the spike protein, which is a protein on the surface of the virus that we want to develop antibodies against. And when the body sees that mRNA, it does one of two things. Either it destroys it or it translates it into the protein, and then your body develops antibodies against that protein. All vaccines work on the same basic principle and that they're trying to deliver a protein on the surface of the virus, that you're trying to stimulate the immune system to develop antibodies against. In this case, instead of delivering that protein directly what you're delivering is a genetic sequence for that protein.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. Doctor Scott Gottlieb, thank you so much, as always. See you next week. FACE THE NATION will be back in a minute. Stay with us.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: Last week the Biden administration outlined several steps aimed at fighting back against both cyberattacks and misinformation campaigns. Chris Krebs is the former director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and now founding partner of Krebs Stamos Group. And he joins us now in person as a real live human here. Nice to see you, Chris.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS (Partner, Krebs Stamos Group/Former Director, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency/@C_C_Krebs): Good to be here.

JOHN DICKERSON: Thank you for being here. Let's start with misinformation. The-- the-- the surgeon general put his finger on misinformation in terms of blocking people getting to vaccines. You fought a lot of misinformation with respect to elections. Do you see similarities between those two?

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Absolutely. And it was a-- it was a remarkable week in terms of pronouncements both from some of the social media platforms, Facebook as well as the administration. What-- what we are seeing here, though, is an ecosystem of information purveyors. Some of this is politically motivated. Some of it is the anti-vax community. Some of it is, you know, profiteering. And I tend to believe that there's a lot of that going on here--

JOHN DICKERSON: Profiteering, people selling quack cures.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Yeah. And-- and there was a-- there was a Washington Post piece the other day about the FTC, a former FTC commissioner, Terrell McSweeny, that asked the FTC to investigate some of this, some of the profiteering off of the pandemic. And I think that is an incredibly important development in how we're going to move beyond not just the pandemic-related disinformation, but also some of the election-related disinformation.

JOHN DICKERSON: And is this different? Is there any foreign meddling in this kind of disinformation? We know about people passing, you know, neighbors who are passing information that isn't square, but is-- are there any foreign entities involved?

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: I think yes, there are. And there tends to be a set of actors. There's state actors, intelligence agents-- agencies. Again, the profiteers, you have conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers. You have political activists as well. In what happens, whether it's elections, whether it's COVID, whether it's technology issues, you tend to have an overlap of these different actors. And when you talk about foreign actors and Russian disinformation specialists, in particular, they-- they don't actually have to do a whole lot because we've done so much here domestically to ourselves. But they get the seeds of division that they then amplify, they drive more activity. And, ultimately, what they're looking to do is undermine our confidence in United States of America, ourselves.

JOHN DICKERSON: We're all ready to fight and they just drop in. I think that creates a new round of fighting. Let me ask you about Facebook. They responded to the administration and said eighty-five percent of our users are interested in vaccines, basically, saying the administration is wrong. But the Center for Countering Digital Hate, which the administration pointed to, said that there were basically about twelve Facebook accounts that are spreading this disinformation. Help us think through what the right way to think about this is.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Unfortunately, both can be true at the same time. So, yes, Facebook and other social media platforms can provide helpful information on the facts behind the vaccine. And the same thing happened in the elections last year. They had a banner and a trust page. But, at the-- but at the same time, there are those that can use those platforms for their own benefits to continue to push disinformation. Now, what has happened over the last several months is that some of those that the-- the Dirty Dozen or whatever they're calling it, some of those have been de-platformed. But the problem is particularly for vaccine disinformation, it is metastasized and it is now, you mentioned it earlier about the top down and the bottom up, the grassroots piece. It is now so pervasive that it exists just naturally within the ecosystem on Facebook and elsewhere. And that's where we need the platform to be more transparent in how their algorithms work, how engagement works, so that outside security experts and researchers can dig in and hold them accountable, that us as consumers of these platforms can hold them accountable and demand better.

JOHN DICKERSON: So we have about fifteen seconds left? Do you mean the structure of-- of Facebook is-- is raising up just regular people who are spreading information?

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Unfortunately, fear sells and those clicks drive more engagement.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. Chris, stay right there. Chris, we'll be right back. We need to take a short break, but stay with us.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: If you're not able to watch the full FACE THE NATION, you can set your DVR or we're available on demand. Plus, you can watch us through our CBS or Paramount+ app.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: We'll be right back with a lot more FACE THE NATION, continuing our conversation with Chris Krebs. Stay with us.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: Welcome back to FACE THE NATION, more with former head of the Cyber Security and Infrastructure Security Agency, Chris Krebs.

Chris, REvil, this is the Russian-based operation that was responsible for the Colonial Pipeline. What happened to them?

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: It's not clear. There are three possibilities. One is that-- that the President meeting with Putin had an effect and the law enforcement or intelligence services in Russia told him to knock it off. That's certainly an option. The second is that some sort of U.S. or allied operation put enough kind of sand in their gears where they decided to pack it up. The third is the theory that Dmitri Alperovitch, formerly of CrowdStrike, now of Silverado Policy Accelerator, is-- has advanced that it's hot in Moscow right now. And these guys just made a lot of money. So maybe they're hanging it up for a couple of months going down to the Black Sea. You know they just picked up some territory there in east-- eastern Ukraine. So maybe hanging out down there.

JOHN DICKERSON: So on the first two theories, the first would be that the Russians are basically proving Biden's case, which is you have control over these people and you can make them stop, which would have implications, wouldn't it, for the-- for the just the general, because the Russians are involved in a lot of bad activities.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Absolutely. And, you know, that would tell them-- tell me that they as you said, they have some authority and some ability to compel action. But that doesn't mean that these folks are just going to go away. They can go to other safe havens. Belarus could be an option where they just move up, pack up operations, and go elsewhere that-- that may provide them a little bit more of a, you know, a comforting environment.

JOHN DICKERSON: Now, let's imagine they go for whichever of the three reasons it is, how easily can they be replaced by an equally creative, malevolent force?

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: I would-- what I would expect to see this team, the REvil team who was previously known as GandCrab, I would expect that they would come back and rebrand in the fall probably some new name, some rebrand, and that gives them the advantage of staying off the radar of law enforcement. And if the administration starts sanctioning some of these ransomware crews, which they've done in the past, that, you know, by changing names, it-- it-- it makes law enforcement in the Treasury Department play catch up.

JOHN DICKERSON: Speaking of playing catch up, so there is now somebody in your old jobs.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Yes.

JOHN DICKERSON: The administration has a lot of players on the field. Give me your assessment of the Biden administration's cybersecurity team, and I'll throw in there something Garrett Graff in Wired wrote about, which is maybe they got so many people on the field, it's going to be hard for everybody to stay coordinated.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: So they-- they have an impressive team. And really-- so, Jen Easterly just came in, was confirmed earlier this week. They also have Chris Inglis, who's the new first national cyber director. You have Anne Neuberger in the White House. You have Rob Joyce at the National Security Agency. It's a-- it's a-- it's almost an embarrassment of riches from a capability perspective and kind of going from the last administration, which was, you know, a much smaller set of cyber experts. There's going to be some adjustments. But CISA, my old agency, now Jen Easterly's agency, is the front door for private sector engagement with the U.S. government. And I really look forward to her in that team continuing to move the ball forward on improving cyber defenses here domestically.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. Chris Krebs, we're out of time. We're probably going to be talking to you a lot more about this issue. So we really appreciate it.

CHRISTOPHER KREBS: Thanks, John.

JOHN DICKERSON: Thank you.

And we turn now to the state of the economy and the recent uptick in consumer prices. CBS News business analyst Jill Schlesinger joins us from Long Island. Good morning, Jill.

JILL SCHLESINGER (CBS News Business Analyst/@jillonmoney): Good morning.

JOHN DICKERSON: So prices are up five percent, it's the biggest rise in thirteen years since August of 2008. What's going on?

JILL SCHLESINGER: Well, there's a lot of different forces. And I just want to point out that a lot of this has to do with the fact that a year ago when we have these price increases, we look back a year, that's when the economy was still mostly shut down. So the effect of looking one year ago is that it seems like this gigantic, big jump in prices. But we also have the confluence of good-old Econ 101: supply and demand. So, obviously, we've been shut down mostly for sixteen months, red-hot consumer demand. There is more than two trillion dollars of excess savings that we have burning a hole in our pockets, and we're spending it big time. And then on the supply side, we've had a lot of bottlenecks in supply in certain areas, and that has really cut off a lot of supply. So you put it altogether, and, as you said, a big price increase even when we take out volatile food and energy, we have the biggest price-- price increases in thirty years.

JOHN DICKERSON: So help us understand what is the result of a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic and this strange coming out of that with an economy, what's going up-- what-- what's increasing and what portion of what's increasing do you think is a result of, say, those bottlenecks you talked about which have to do with the pandemic, and-- and what portion of what's increasing is likely to maybe stay higher as the economy recovers?

JILL SCHLESINGER: Well, I think it's important to note that economists are battling this very question right now. And we don't know the answer. Here's what we do know, the things that went down the most in price during the pandemic are seeing huge increases. So everything in leisure and hospitality has gone sky-high. You know go look for a hotel right now, go try to fly, it's tough. Okay. But then what other areas, as we talk about those supply chains, semiconductor chips are really in need right now. And those are needed in cars because new car production stalled in the beginning of the pandemic, very few suppliers thought that there's going to be this huge demand for cars. Well, no new cars, let me go to the used car market. Wait a second. There are used cars that are up forty percent in price from before the pandemic. This is a huge number. Those kinds of bottlenecks will not continue. But I think the area that economists are most worried about is everything else. And that means that we've got to watch wages, we've got to watch food prices. Clothing and apparel was up very big. And it is unclear to anyone at this moment in time how much of that will stick and for how long.

JOHN DICKERSON: Jill, what about-- I mean, wages are a part of this as well. We hear about labor shortages, and-- and you see companies in the fast-food industry adding more not only to the paycheck, but also benefits. How much are wages a part of this picture, and what do you think the durability of that is? Will that change? Or will they go back down again?

JILL SCHLESINGER: I think this is a really interesting question because for so many years it really felt like employers had the upper hand. And through the pandemic, because there was a lot of ability for people to stay home, we wanted them to stay home, people were really happy to collect the money and be safe, and that was smart. Now we have smaller companies, specifically, complaining they cannot find labor. Now a company like McDonald's or a Starbucks or an Amazon, they can pay up. They've made gobs of money throughout the pandemic. No problem. I think the concern is around some of the smaller employers. The mom-and-pop stores, they are saying we can't find people, we can't afford to pay these wages to compete with the big guys, and we're getting squeezed out. Now if you're a worker, you're feeling pretty good. But remember one thing, we have to really look at these prices because if prices are up by five percent and you only have a three-percent increase, you're losing. In fact, the Labor Department said that if you look at the average wages right now, from a year ago, and you account for inflation, we actually are making 1.7 percent less than we did a year ago. And that's not a great condition for workers.

JOHN DICKERSON: With thirty seconds left, Jill, we can't talk about inflation without talking about the Federal Reserve. What's your sense of what the Federal Reserve will do in response to these signals of inflation?

JILL SCHLESINGER: Well, remember, the Fed has basically two jobs: they want to foster enough economic growth to get people in the labor force; and they want to keep an eye on prices. For ten years prior to the pandemic, they were worried that prices were not rising enough. Now they've got to focus on inflation. The Fed chair, Jerome Powell, has said that the Fed is willing to let inflation run hotter for a little bit longer to get the millions of people who are not yet back in the labor force back in. So I think that we are going to see higher prices at least for another six months. Next year, that's another question. John.

JOHN DICKERSON: Jill, thanks so much for breaking it all down for us.

We'll be back in a moment.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: A number of books have been published recently about Donald Trump's presidency. One episode contained in many of them, as well as a New Yorker article this week by Susan Glasser, stands out. General Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, spent the final months of the Trump administration worried that the President would use the military to stage a coup to deny Joe Biden the presidency or launch hostilities against Iran as a way to stay in power. What makes this story notable is the stature of its main character. Milley is not some low-level campaign aide. He is the nation's top military official, whose job required close work with Mister Trump. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs must scan the horizon for dangers and devise plans to meet them. He advises the President about what he can do about threats. But, in this case, it was what the President might do that Milley thought was the threat.

For insight into this episode and the questions it raises, we turn to a man who held Milley's job before him, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, who joins us from Hilliard, Ohio. Good morning, Admiral.

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN (Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff): Good morning, John. It is good to be with you.

JOHN DICKERSON: It-- it's good to have you here. You were chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. What do you make of this episode?

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN: Well, I think the reporting, from what I understand, has been pretty accurate, pretty chaotic time, particularly after the election and the two threats that you talked about, the external one, and whether or not we would commence some kind of combat or conflict with Iran and then the internal one in terms of where it might go, particularly with respect to how the military would be used by President Trump to somehow validate that the election actually was a fraud and keep the President in power. I think that's all very accurate and, obviously, incredibly disturbing, literally in every respect.

JOHN DICKERSON: And it's fair to say you don't train for those kinds of eventualities with a Commander-in-Chief.

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN: No, you don't. Although I think General Milley and others who've served over the last four years would tell you it's been a very chaotic environment, very difficult to predict what was going to happen from day to day and great concern with respect to the possibility of, you know, some of the orders that might come the military's way, which generally will go with the advice of the chairman and certainly directly to a combatant commander--

JOHN DICKERSON: Mm-Hm.

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN: In the case of Iran, it would go to Central Command. And so the chairman's got-- in this case, General Milley, I thought, really did the right thing on both fronts, quite frankly. I don't think he was alone with respect to Iran.

JOHN DICKERSON: Yeah.

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN: But I think on the-- on the internal potential for a coup, you know, Milley really stood up, did the right thing, and I think made the case that he was the right officer to have in the right job at the right time in a-- in a very, very difficult, stunning, and unprecedented situation.

JOHN DICKERSON: Help us distinguish between garden variety conflict between a chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a President and what we're talking about here. Because I know President Obama wrote in-- in his book about once being, you know, in a tough conversation with you. Those are you-- those are-- those happen in that job. But that's something quite different from what Milley was worried about. Right?

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN: Absolutely. Every chairman for the four years that he's there has huge challenges, and-- and so you get into some very, very tough, heated debates about what, you know, what's recommended or what's going to be done in a given situation. But, in the end, you know, the-- the chairman and the military leadership, once the President makes a decision, you know, we carry it out. There's no discussion with respect to that. In this case, you know, clearly, had President Trump decided to use the military against the American people and somehow create an opportunity for the President to stay in-- in place, that rubs up or actually it's contrary to the Constitution, which is what the military serves, as opposed to the President, and could be seen as an illegal, immoral or unethical order, in which case, you know, General Milley and the rest of the military leadership, the other four stars, in my view, would be-- would be required to either resist or if they're unable to resist, resign.

JOHN DICKERSON: One of the turning-point moments for General Milley was the President's walk-through Lafayette Park, in which General Milley walked with him, clearing protesters for a photo op. You wrote-- you spoke out after not speaking out about the Trump administration in an article in The Atlantic and said that you were worried about the military being used in political ways. That was a turning point for you and for General Milley. I guess my point is these-- these episodes in his book were a part of a growing trend. It wasn't just what happened at the end of the Trump administration. You-- you had fears about the politicization of the military long before that.

ADMIRAL MICHAEL MULLEN: I do. And-- and I did and I continue to have them even now, because the political environment is-- is so intense and so divided and we need to work hard to make sure the military doesn't become part of what is politicized in this country, I think as far as Lafayette Park is concerned, you know, General Milley spoke publicly very quickly thereafter and readily admitted he made a big mistake with respect to literally from June until-- until after January 6th, when Milley really started to be concerned about what was possible. His antenna was up. He knew the right thing to do. He knew-- he knew how to do it, as best you could figure out, and what is a very, very fluid situation. And then he executed accordingly. So, I think he more than made up for that mistake that he made surrounding Lafayette Square.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. Admiral Mike Mullen, thank you so much for being with us and helping us put all of this in context. We really appreciate it.

And we'll be back in a moment.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: Since the November election, seventeen states have enacted new laws that tighten rules around casting ballots and running elections. In an effort to keep Texas from becoming the 18th, Democrats in the state legislature staged a dramatic protest, flying to Washington, to block Republicans from passing a more restrictive voting law. To help us put those challenges into perspective, we're joined by David Becker, the director and founder of the Center for Election Innovation and Research. Welcome. Nice to have you here, David.

DAVID BECKER (Executive Director and Founder, Center for Election Innovation and Research/@beckerdavidj): Thanks. Great to be here, John.

JOHN DICKERSON: There's a lot going on. So just put us-- give us the basic perspective of what's going on with all of these different voting rights efforts?

DAVID BECKER: So we're seeing a lot of highly partisan efforts to make it harder for some people to vote. They do appear to be targeted in some ways to ensure that in particular the Republican Party right now might be perceived to have a better chance of winning some elections. But what I'm also very concerned about are unprecedented efforts to inject toxic partisanship into the counting of ballots and the certification of election results that occur during election and after an election, where you're going to see potentially chaos from things like what we're seeing in Texas, where they're introducing efforts to allow for partisan poll watchers to roam free within the polling place, interfering with the process. Where we're seeing efforts to criminalize activities by professional election administrators who are trying to make it easier and more efficient and more secure for elections to be run. We've never really seen that before and it could be potentially a national security issue.

JOHN DICKERSON: So I'll get to the national security issue in a second. But, essentially, do we have two baskets of concern here. One is limits and challenges to just getting to the polling place and the right to vote. And then the second is what you do after those votes are cast and who gets to oversee them and who gets to question them and that kind of thing. Are those the two basic categories?

DAVID BECKER: I think that's basically right. And-- and it's-- and it's important to note that these are all being based on a complete lie that the election somehow some-- had some irregularities. We're now well over eight months past the election. The losing candidate hasn't brought forth any evidence that's been considered by any court or anywhere else that's been valid that the election was not secure. And, in fact, this election was, as the Attorney General-- as Attorney General Barr said, as the DHS said under Trump, as the FBI said, and as many others said, this was the most secure and transparent and verified election we've ever held in American history.

JOHN DICKERSON: Yeah, actually-- just reset the table here. How many actual people, humans, have been charged or anything with fraud in 2020, in the whole country?

DAVID BECKER: I mean, very few. It's a handful. I believe it's under ten at this point in time. The total number of potential fraud cases that we might see in election of this size, a hundred sixty million people voted in November, which is amazing. But the total number of fraud cases we might see is going to be measured in the dozens, out of a hundred sixty million, not anywhere near anything that could have affected the outcome.

JOHN DICKERSON: So back to your-- the two categories you were talking about, the problems with voting and then the problems after the vote is cast. Republican leader-- Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell said these are commonsense measures out in the country. They're just trying to unwind the measures that were brought in under the age of COVID and-- and sort of restore things to the way it was before. Is-- is that an accurate characterization of the scope of things that are being suggested?

DAVID BECKER: I don't think it's entirely accurate. I think what we're seeing in light-- it's always a good idea after an election to look at what actually worked based on facts, and maybe consider ways to improve that. And there are ways to increase integrity while also increasing access. What we're seeing here are things like in Georgia, for instance, where they ran not only the most successful highest turnout election they've ever held, they actually ran two of them within a two-month period of time. But they did this with paper ballots for the first time in two decades, and they were able to count every one of those presidential ballots three times, three different ways once entirely by hand. We should be applauding those efforts. I think another thing that's really important here is when we talk about election integrity, it is actually good for election integrity when we have more people voting in different ways over a period of time. We don't want to have a single point of failure on Election Day, where if something goes wrong, we can't fix it. If we learn of a problem at 1:00 PM on Election Day, it's very hard to fix by the time the polls close. But if we have people voting by mail, people voting early in person, and people voting on Election Day as we saw in most states in 2020, we can actually find problems early and fix them so they don't affect the outcome of the election. That's a very good integrity measure.

JOHN DICKERSON: So is-- so if-- if those ways of voting are limited, then does that mean there is the opportunity for more chaos? Is this what you were talking about in terms of national security? There is more opportunity for chaos, and our-- America's enemies love opportunities for chaos.

DAVID BECKER: That's right. Imagine now we're in a highly partisan environment, we're concentrating more voting on Election Day in polling places where there might be long lines, where partisan poll watchers have free reign to engage in chaos, and then we are now injecting partisanship into the counting and certification process where partisans might be tempted to overturn the will of the people and they are somewhat empowered to do that by their legislators. This is something-- this could be a void that our adversaries see and try to exploit in some ways.

JOHN DICKERSON: So in about the last thirty seconds we have, tell me about what your sense is the prospect of abilities to push back against some of these measures that you find alarming, that Democrats certainly find alarming, either in Congress or at the local level?

DAVID BECKER: Yeah, we don't have many ways to fight back at this point. We've-- we've gone seven months into the year. Clearly, one thing we need to do is everyone needs to stand up and say this election was valid, it was secure, and applaud the election officials who ran it. But, secondly, maybe Congress does have a small window here, where Republicans and Democrats of goodwill can come together on a-- on some kind of bill that actually could establish a foundation for democracy that could get fifty votes. So far we haven't seen an election bill that could get fifty votes. And so the filibuster is not necessarily relevant at-- as of yet.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. I'm going to have to cut-- cut you off. We're out of time, David. Thanks so much.

And we'll be right back.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: Last night the sanctuary of a summer night's baseball game here in Washington was pierced by a terrifying interruption.

MAN #1 (MASN/MLB): Eight to four and--

JOHN DICKERSON: The Nationals and San Diego Padres' game was interrupted in the bottom of the sixth inning by a shooting outside the stadium. Players quickly left the field. Fans were told to shelter in place.

MAN #2: We ask you to remain inside the stadium at this time.

JOHN DICKERSON: Nobody inside was in danger, though, outside three were shot in an incident that is becoming more and more familiar across the country. The game will resume this afternoon.