Full transcript of "Face the Nation" on December 1, 2019

On this "Face the Nation" broadcast moderated by Margaret Brennan:

- Sen. Cory Booker, D-New Jersey, (@CoryBooker)

- David Rubenstein, "The American Story: Conversations With Master Historians"

- Michael Duffy, "The Presidents Club: Inside the World's Most Exclusive Fraternity"

- Susan Page, USA Today, "Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Arc of Power" (@SusanPage)

- Jon Meacham, "The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels" (@jmeacham)

- Ruth Marcus, Washington Post, "Supreme Ambition: Brett Kavanaugh And The Conservative Takeover" (@RuthMarcus)

- Amy Walter, The Cook Political Report (@amyewalter)

- Jeffrey Goldberg, The Atlantic (@JeffreyGoldberg)

- Jamal Simmons, HillTV Host and CBS News Analyst (@JamalSimmons)

- Ben Domenech, The Federalist (@bdomenech)

Click here to browse full transcripts of "Face the Nation."

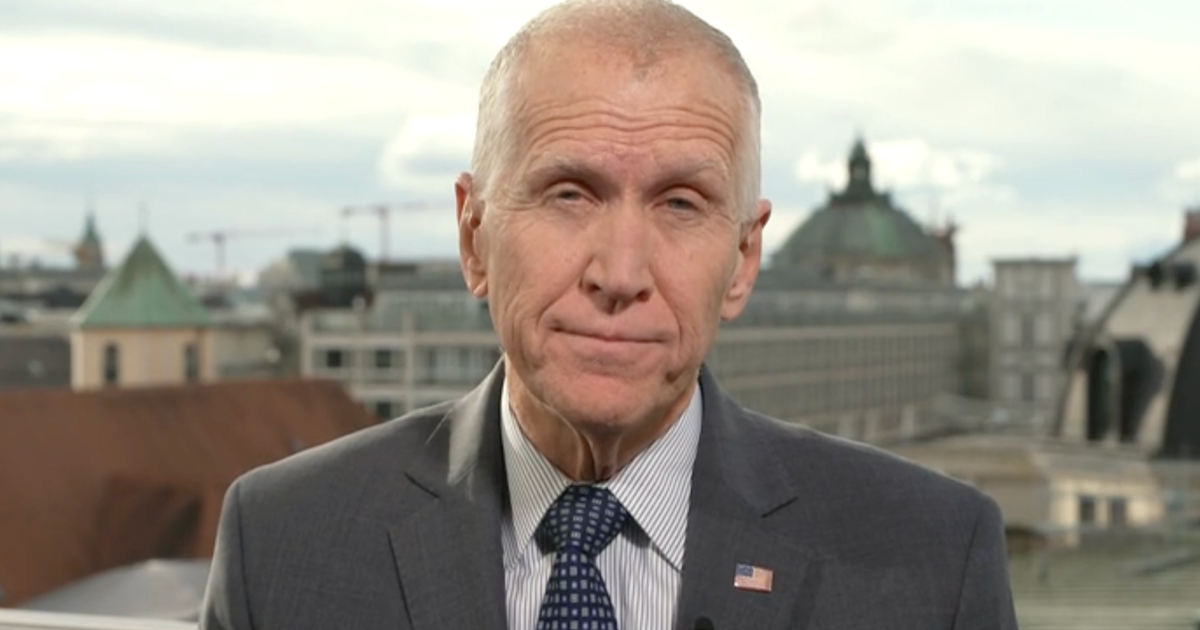

JOHN DICKERSON: It's Sunday, December 1st. I'm John Dickerson and this is FACE THE NATION.

It's been a quiet Thanksgiving week in Washington, which has meant fewer news alerts and a little more room for tradition.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Today I will issue a pardon to a pair of very handsome birds.

JOHN DICKERSON: But the President couldn't stay entirely away from the topic that's been dominating the headlines.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: They've already received subpoenas to appear in Adam Schiff's basement on Thursday.

JOHN DICKERSON: The turkeys retired to a safe house and President Trump then made a surprise trip to Afghanistan, honoring another tradition by serving holiday dinner to American troops. It wasn't the only surprise. He also declared that the U.S. was back in peace talks with the Taliban.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Taliban wants to make a deal, and we're meeting with them, and we're saying it has to be a ceasefire. They didn't want to do a ceasefire, but now they do want to do a ceasefire.

JOHN DICKERSON: It was an announcement that confused many, including the Afghan government and the Taliban, who nevertheless suggested they were willing to start talks again.

JOE BIDEN: It's like he's playing monopolism. For the sake of the country I hope he accidentally gets it right.

JOHN DICKERSON: Here at FACE THE NATION, we'll honor our own Thanksgiving tradition where we'll talk with several of our favorite authors and historians about the presidency, politics, and patriotism.

Plus, as some 2020 Democrats spend their holidays looking for votes in Iowa--

CORY BOOKER (Campaign Ad): I'm here today because of love.

JOHN DICKERSON: --New Jersey Senator Cory Booker is one candidate searching for something more meaningful.

CORY BOOKER (Campaign Ad): The truth of America is that we win when we come together and show the best of who we are.

JOHN DICKERSON: But is that vision possible? As the country and Washington prepare to get back to business. We'll talk with Senator Booker.

And we'll have political analysis on all the news of the week just ahead on FACE THE NATION.

Good morning and welcome to FACE THE NATION. Margaret is off today. The House Intelligence Committee announced last night that their impeachment inquiry report will be ready tomorrow. Then Tuesday the full committee will vote on whether or not to proceed to the next step, which is asking the Judiciary Committee to look at writing articles of impeachment against President Trump. We will discuss those developments, but we're also going to try to step back a little today to reflect on presidents and partisanship and the pace of an age where one development follows quickly on the heels of another. We will be-- we will begin, though, with campaign 2020. New Jersey Senator Cory Booker is one of the Democrats trying to win his party's nomination. And welcome, Senator.

SENATOR CORY BOOKER (D-New Jersey/@CoryBooker/Democratic Presidential Candidate): John, it's good to be here. Thank you.

JOHN DICKERSON: Thanks for coming off the campaign trail for a nanosecond to join us. You have a new ad out and I want to talk about that ad and where we are in American politics today. Your ad comes at a time where your campaign is, you know, struggling to stay alive. You're trying to get on the next debate stage. Your message in the ad, you talk about love and unity. You've talked about that throughout. Is that message not selling?

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Well, it is in a sense that right now we see from local leaders in Iowa, New Hampshire, there's no candidate that has more endorsements than I do from folks that are on the ground trying to make things happen for American people. We see my favorabilities now number three in net favorability in Iowa. So it's working it's not translating to people choosing me in the polls. This is why we're pushing more ads and hope people will go to my website, make contributions so we can do more of that. But I didn't get in this election because of any other reason that I thought the most important thing we needed in this country is try to affirm that the lines that divide us are not as strong as the ties that bind us. I'm running for President because I think the next President, especially after this person, has to be a healer, has to get us back to putting indivisible back into this one nation under God, because I see this in Washington. We're so-- the partisanship is becoming tribalism. We're hating each other because we vote differently and-- and we're not going to be able to get the big things done that we need to get done, like facing down climate change, the health care crisis that still persists. You need new American majorities to get that. And you need a leader that can inspire the moral imagination of this country.

JOHN DICKERSON: So President Obama had a version of that when he ran for-- for the presidency and he came to Washington. And by the time he left, he basically felt-- and the Republicans have their view about him, but he felt about the Republicans they were not willing partners. If he couldn't do it, things have gotten worse since, why is President Cory Booker going to be able to do it?

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Well, two things. One is I'm glad you mentioned that he won with that message. I do think that we need the leader who can best inspire that Obama coalition. But number two is when I took over a city that was known for crime and corruption, I think most of the mayors before me were indicted and convicted. People told me all the things we could not do. And my-- my frustration was hearing all these things that people said couldn't be done. It undermined. It sort of was like a surrender to cynicism that I think we have to resist. So I-- I'm going to come to Washington and do things differently. I'm going to break norms like this President is doing to demean, degrade, and divide--

JOHN DICKERSON: What norm are you going to break that's going to make this city, calcified as it is, suddenly break open and a group hug?

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Well, first of all, that's not what I'm looking for. I think our debates and our-- are important. There are going to have to be tough discussions. But this is what frustrates me. The majority of Americans agree on common sense gun safety reform. The majority of Americans agree on the need for massive infrastructure investment. The majority of Americans agree that we need to raise the minimum wage. This is the frustrating thing is that we have this wide berth on which we agree so our politics is not reflecting the people. And that's what I'm going to change as the next President of the United States.

JOHN DICKERSON: Is your campaign facing a do-or-die moment in terms of getting on the debate stage?

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: It-- it-- it is facing one of those moments where-- and people have responded to this before, that if you want me in this race, if you want my voice and my message, which is resonating, then-- then I need help. We need people to go to corybooker.com and contribute so that we can do what I see a lot of the billionaires in the race now doing, which is just running non-stop ads to boost their-- their poll numbers. I'm not taking corporate PAC money. I'm not taking a lot of the money-- I'm-- I'm running on individual contributions, and that's what we're going to need to keep doing.

JOHN DICKERSON: President Obama a couple of weeks ago said the country is not really ready for revolution and that what he hears coming out of the Democratic race is maybe a little bit of too much change. Where do you come down on that? If-- if a Democrat is elected, it's going to be after four years of-- of President Trump, where there's been a lot of excitement. Is the country going to be ready for a lot of Democratic version of excitement?

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Look, I-- I-- we need a inspiring, igniting leader next. Someone who can get folks energized because-- I'm here because of revolutions. The civil rights movement was a revolution. What happened at Seneca Falls was a revolution. But these are revolutions that are consistent and resonant with our founding ideals. Look, the Declaration of Independence, they knew that this was a nation that was an experiment. If you read that document at the end, they actually have a declaration of interdependence where they say that if America is going to make it, we have to mutually pledge our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor. That's what I think we need this next revolution to be about, is about this understanding that our enemies, they literally-- I've read the intelligence reports, the Russians, the more we are divided against each-- ourselves, they are using strategies or social media platforms more to make us hate each other more. This next revolution has to be one where we understand we have common cause. If your kids don't have a great public school to go to, my kids are lesser off. We've got to understand that we're all in this together.

JOHN DICKERSON: One last question I want to ask you.

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Please.

JOHN DICKERSON: It's something you mentioned in the debate. You-- you said this in the debate, "We lost in Wisconsin because of a massive diminution in the African-American vote. We need to have someone who can inspire African-Americans to the polls in record numbers." Polls show right now that Joe Biden gets forty-nine percent among African-Americans. That's thirty-four points better than his closest rival.

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Yeah.

JOHN DICKERSON: He seems to be doing exactly what you're saying. He is inspiring African-Americans, so who are you talking about?

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Well, first of all, he's got the loyalty and voting right now because he's got a hundred percent name recognition and is our former vice president, but you know this, that Barack Obama was behind Hillary Clinton amongst black voters until he won in Iowa. This race, most people have not made up their mind, and as a guy who has shown statistically in New Jersey when I'm on the ballot, surges in African-American vote, I am confident I'm the best person in this race--not to just get the percent of the African-American vote, but to increase the base, increase the turnout in a significant way. That's the kind of leader we're going to need on the ticket in the next election.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. Senator Cory Booker, thanks so much for being with us.

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Thank you, John.

JOHN DICKERSON: Appreciate it.

SENATOR CORY BOOKER: Thank you very much.

JOHN DICKERSON: And we will be back in one minute with our political panel. Don't go away.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: And we're back after a quick change with our political panel. Amy Walter is the national editor for The Cook Political Report, Jeffrey Goldberg is the editor-in-chief of the Atlantic, Ben Domenech is the publisher of The Federalist, and Jamal Simmons is a Democratic strategist who works for Hill.TV and he is also a CBS News political contributor. Welcome to all of you. And I don't know if you can hear the rain but it's--

AMY WALTER (Cook Political Report/@amyewalter): Yes.

JOHN DICKERSON: --we're going to pour down opinions right now. Ben, I want to start with you the impeachments. We basically have known about this story for about eleven weeks. What is the defense of the President? Is it that he did nothing wrong or is it that he did something wrong but it's not impeachable?

BEN DOMENECH (The Federalist/@bdomenech): I think that some Republicans are taking from column A and most Republicans are taking from column B. The response that you heard from Will Hurd just a couple of weeks ago after the hearings were winding up is one that I've heard from a lot of Republicans that say that they are uncomfortable with what the President did, but they don't believe that it rises to the level of impeachment. One of the things that I think has actually aided Republicans in this is that this has become more of a process story as it has gone along one where they can go into different rabbit holes and directions as opposed to maybe plowing ahead with the argument that the transcript itself is impeachable, which was something that we heard from Democrats early on.

JOHN DICKERSON: Jamal, what Ben talks about the rabbit hole defense is what the Clinton impeachment folks did. They try and get to be everything but about whatever the main thing is. If a Democrat stopped somebody on the street and says this is the main thing, what is the main thing?

JAMAL SIMMONS (Hill.TV/@JamalSimmons): The main thing is that the President of the United States tends to use national policy in whatever he does for his own personal benefit, not for the benefit of the country. And if you look at this not just in the Clinton example, unless you remember Bill Clinton took responsibility for what it is he did in August of 1998, which gave Democrats the permission to sort of lambaste him before that election, which Donald Trump is not going to do.

JOHN DICKERSON: Right.

JAMAL SIMMONS: But let's take it out of that context and look at more as the Hillary Clinton Benghazi investigation--

JOHN DICKERSON: Mm-Hm.

JAMAL SIMMONS: --where the Republicans branded Hillary Clinton in the course of that Benghazi admis-- investigation, and she was never really fully able to get out from underneath that shadow that they cast over her in the process.

JOHN DICKERSON: Clinton is saying wrong but not impeachable, Donald Trump has said done nothing wrong so far.

JAMAL SIMMONS: Don't do that. He's-- he punishes you for trying to do that.

JOHN DICKERSON: That's right. That's right. Amy, you were down in South Carolina, there were some ads running--

AMY WALTER: Yes.

JOHN DICKERSON: --anti-impeachment ads running. Tell me against Joe Cunningham?

AMY WALTER: He's a brand-new congressman from this district that Trump won easily.

JOHN DICKERSON: He's a Democrat?

AMY WALTER: He's a Democrat. If you are a Republican right now, your hope is it's putting people like Joe Cunningham who came in in this big wave in 2018, pledging to be something different, pledging to be bipartisan, a lot of what Senator Cory Booker was talking about, right? We're going to focus on the issues; we're going to break sort of this he said, she said in Washington and find solutions. Now, the knock on folks like Joe Cunningham and other the freshman is he said you were coming here to fix things, now you've just turned into a partisan Democrat just like Nancy Pelosi or whoever else in leadership. They're hoping that that's going to work out in the election in 2020. My guess is, by the time we are even in the spring or summer of 2020, we're not going to be talking about impeachment at all. And this is the most remarkable thing about this impeachment process is, this will be the third time in history a President of the United States will be impeached and I will bet you it's not an issue at all in the 2020 election.

JOHN DICKERSON: So, Jeffrey, what Amy is saying, then, basically is this is just another thing after the last thing and it will be superseded by the other things.

JEFFREY GOLDBERG (The Atlantic/@JeffreyGoldberg): A lot more things.

JOHN DICKERSON: Yeah, yeah. So that it seems to me works in the President's benefit. Which is, this is just another thing. It's the-- it's that, you know--

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: Not only to his benefit, if he comes out a winner, he comes out a winner. I mean, he says I defeated this attempt to remove me that your-- your tribune to the sixty million plus people who voted for him. There was a concerted attempt to remove me and I was not removed, therefore, I am stronger now than I was before. And by the way going back to something you were talking about, you know, he-- the argument, the best Republican argument right now probably is this-- this motion that all foreign policy, all national security policy, all aid making is quid pro quo, right? But, of course, we want something back for the money that we give out. The difference here, of course is that-- that usually that is done on behalf of national interest, not personal interest, but he can muddy that very, very nicely if he-- if he tries hard.

JAMAL SIMMONS: But, John, let's-- let's not get past this. Impeachment stains are really hard to washout. You know we have had three impeachment processes that occurred and neither Al Gore, Gerald Ford nor Horatio Seymour who was the Democratic nominee in 1960-- in 1868 were able to take the White House after their party-- the president of their party went through impeachment process, it's very hard. And with the Bill Clinton impeachment, while the Democrats were able to hold on to or win the Congress back, keep in mind, not just Al Gore, Hillary Clinton ran for President twice and wasn't able to get the White House. It's very hard. So we haven't seen an incumbent President run for election before. So we really just don't know how it works out.

BEN DOMENECH: At the same-- at the same time I think it's impossible to say to Jeff's point that the President getting the approval of a bipartisan majority of the Senate against removing him from office, one which would include potentially the votes of Joe Manchin and-- and potentially other Democratic senators as well, is not something that he's going to point to and say, look, they've just have been trying to get me all along, this is all just a big, you know, hoax.

AMY WALTER: Except the true--

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: And they lost and Iowa then lost--

AMY WALTER: Right.

JOHN DICKERSON: It's all about losing your state from the Senate.

AMY WALTER: Except that opinions of this President don't move no matter what happened.

JAMAL SIMMONS: They don't. They don't.

AMY WALTER: That's what I am saying that how you feel about Donald Trump will tell you how you feel about this impeachment process. If you have disliked him all along you think this process has been above board and it's exactly what Democrats should be doing. If you like him, you think that this process has been a witch hunt, and really very little that's going to come up between now and the election is going to change your opinion of that or of him. And so I don't know that it helps him necessarily to say, I won, because they are coming to get me. Opinions about him are-- he is as unpopular in many parts of America today as he was before the impeachment process started. And he is as popular in places where he was before the impeachment process started.

JOHN DICKERSON: Jeffrey, you-- the Atlantic has a cover on the civil war and-- and how to avoid one--

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: Mm-Hm.

JOHN DICKERSON: --in this country. This seems to be ground zero for the moment, the civil war until the next-- we have the next fight over something else.

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: Right.

JOHN DICKERSON: What-- what's your-- what's your feeling about those larger clashing forces in America and how they play out--

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: Right.

JOHN DICKERSON: --through this?

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: Impeachment is just a symptom of the Trump presidency, which is just a symptom of larger cultural and political divides, even regional divides in-- in some ways. Yeah. The-- the special issue of the Atlantic we did is-- is, we're not suggesting that it's 1860 right now or even 1850, we're just suggesting that demographic changes, change in the way we communicate with each other, changes in a whole raft of areas have made it harder and harder to think of this country as a unified force where Americans no longer (INDISTINCT) from Jim Mattis, Americas don't seem to have affection for each other in the way that they used to and we're just trying to understand that. And again, you know, Trump for all the-- the obsession that we have--we're talking about Trump today, Trump is a symptom of-- of larger issues, larger dislocations, larger changes in the way we talk to each other, larger ways in the way we understand common reality, what used to be a common reality.

BEN DOMENECH: And there's downsides for the world of that type of divide within the American nation. As you look around the globe today, we see all sorts of different things happening. We see what's happening in Hong Kong, we see what's happening in Iran. We see what's happening in the degradation of the state of Mexico. We see North Korea. These are all areas where I think we should be focused on them. They're incredibly important and, yet, the focus in Washington has been on this impeachment battle and I think it's degraded the conversation that we ought to be having about these very important human rights issues.

JAMAL SIMMONS: Well, you know, in 1964, Robert Kennedy went to convention floor and gave a speech about America being strong abroad so that we can handle our problems at home. It seems like now we are in the reverse. Even Kamala Harris has said this, America needs to deal with this racial and-- and economic issues at home and in order so we can be strong abroad, and until we not just deal with Donald Trump, but we deal with the economic dislocation of so many communities in this country, it just seems like we're never going to be able to assert the American leadership that we're all used to.

JEFFREY GOLDBERG: We have managed over years to-- to do both things at the same time. We have been able to-- to project power, project our influence and also deal with some of the issues that we have now. We're in a unique position in that we seem totally paralyzed. Everybody knows we're paralyzed.

JOHN DICKERSON: We're going to have to go out the door in a second, but, Amy, I'm going to give you the difficult task of--Dan Balz wrote today about the Democratic race.

AMY WALTER: Yeah.

JOHN DICKERSON: The Democratic presidential campaign has produced confusion rather than clarity.

AMY WALTER: That's right.

JOHN DICKERSON: In the forty seconds we have left, clarify what the state of the Democratic race is for us.

AMY WALTER: The state of the Democratic race is that you have a national front-runner named Joe Biden, who's losing in the first two contests. And in traditionally the first-- the winner of the first two contests Iowa and New Hampshire on the Democratic side has gone on to win the Democratic nomination, where Joe Biden succeeds is in the next two states, Nevada and South Carolina, which are populated with more voters of color, and so we're in a situation right now where you have four candidates right now who have the prospect at least of being calling themselves a front-runner, but by the time we get through South Carolina, we could have none of them as the front-runner. In that, they all can claim a piece of it.

JOHN DICKERSON: Right. Which is when Mike Bloomberg thinks he's going to turn the…

AMY WALTER: That's right.

JOHN DICKERSON: That's the end of it for all of us.

AMY WALTER: Thank you.

JOHN DICKERSON: Thanks to all of you.

JAMAL SIMMONS: Thank you.

JOHN DICKERSON: And we'll be right back in a moment. Stay with us.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: For six years billionaire philanthropist David Rubenstein has hosted dinners for lawmakers at the Library of Congress, each featuring a modern historian. Rubenstein has published a collection of the dialogues in The American Story: Conversations with Master Historians. We spoke with him last week and asked why knowing the past is so important to understanding the present.

(Begin VT)

DAVID RUBENSTEIN (The American Story): The theory of history is that we can learn from what we made mistakes about before, and what we did right before, and then maybe we can do better things in the future. Civilization is all about improving things and if we don't improve in the past, how are we really advancing civilization?

JOHN DICKERSON: When members of Congress come to these gatherings, bipartisan, do you find that they ask questions with a specific intent because they want to use it in their own lives?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: It's like an era of good feelings when the dinners occur. There's no bickering. Members from the opposite parties sit together. Members in the opposite house sit together. And it's-- you wouldn't know how rancorous the atmosphere is in other parts of Washington, but it's like a time where they put a truce down and they come together.

JOHN DICKERSON: Do you see anything or have the historians been able to give these members of Congress any guidance on how they can break out of what they all agree is a time of hyper partisanship?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: I don't think the historians are trying to lecture members of Congress of what they should do. They're just saying, I wrote these books. Let me tell you about these great figures and you take the lessons away from them that you will.

JOHN DICKERSON: Have you had a moment or a time in your career where the lessons of history have really been applicable?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: Well, as a young man, when my hair was dark and I was much thinner, I worked in the White House under Jimmy Carter. I wish I had as much knowledge of history then as I do now.

JOHN DICKERSON: He was a disrupter of the system. He had won the presidency when people didn't think he would. And they came to Washington saying, we're not going to do things the old way. Would a little lessons of history have been helpful to the Carter team when they came in?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: Well, I think in hindsight, we made some mistakes and I would take the blame for it as long as-- as well as other people who were involved in the system as well. But we did some very good things. We did say we're going to shake up Washington. And-- and Jimmy Carter came up with a very unique idea. He said, I'm not a lawyer. I'm not from Washington. And that was unique at that time. And he kind of used that populist appeal. When we came to Washington, we probably didn't have as much breadth of knowledge of people who had served in Washington before. But in hindsight, President Carter was president for only four years and we did enormous number of things. And today, the amount of legislation we passed in that four-year period of time dwarfs what's getting done today.

JOHN DICKERSON: One of the things you have asked these historians when you've talked to them is if you could talk to one former President and ask them a question, which one would it be? So for you what former President, if they were alive today, would you-- would you want to talk to him? What would you ask them?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: In my view, in our long history in this country, the greatest American, without doubt is Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln held this country together because it wasn't obvious to people that the country should stay together. I'm not sure any other person who we elected President would say to the south, no, we're not going to let you go away. So I would ask him two questions if I had a chance to have dinner with him. One, why did you feel was so important to have the south stay as part of the country? Why not let it go away? And, secondly, were you convinced that ending slavery through the Emancipation Proclamation was the only way to win the war? And are you pleased that you ultimately freed the slaves? And why did you not do it earlier?

JOHN DICKERSON: When you look at Lincoln, he came into that job with a kind of patchwork of experience and a lot of failures. What do you see in his background that-- that tells us about Lincoln's success?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: He probably didn't have more than a second-grade education. He taught himself how to read. He loved to read, but he really didn't have a classic college education. He didn't really go to law school. He took the people who were more likely to be president or presidential nominee of his party and he brought them together in his cabinet, and he really took the best of their knowledge. And in the end, those people idolized him. Abraham Lincoln's great talent was that he didn't take himself too seriously. He had a great sense of humor. He knew how to write extremely well. He had a way with words that really no President has really had since that time.

JOHN DICKERSON: Which President, when you started becoming a presidential historian yourself and so interested in them, which one was the first one that you really got turned on to the presidency about?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: I think President Kennedy was somebody that took my generation and said, come in and give back to your country.

PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY: Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.

(Crowd cheering and applauding)

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: And it inspired me to go into public service. And many people in my generation were similarly inspired.

JOHN DICKERSON: And you've dedicated your life to public service in one form or another. What do you think is the state of that notion in America, the ask not notion?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: I think Americans want to make the country a better country. But I think it's-- what has changed from President Kennedy's time is that many people think you can help your country as you can without having to go in the government service. There are so many NGOs today, so many ways to serve your country in nonprofit areas that do not require you to be on the government payroll. But I then also think many people in our country don't feel that government service is as noble a thing as it once was. And in fact, we tend to denigrate government servants much more than we do.

JOHN DICKERSON: Is there danger--

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: Than-- than we should, I should say.

JOHN DICKERSON: Is there a danger to that-- that--

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: There is. For example, it's very easy to make fun of members of Congress. And-- and you can always get a joke by making fun-- fun of members of Congress. They're relatively modestly paid. They have an incredible lifestyle in terms of how much work they have to put in. And they're under enormous amounts of pressures and we don't realize the burden they often face. But we-- you can still make fun of very few people in our country. You make fun of lawyers. You can make fun of private equity people. You might be able to make fun of members of Congress and you won't get criticized for making fun of members of Congress. But actually, they're pretty good public servants and we should honor them more. I think we should actually pay them more.

(End VT)

JOHN DICKERSON: And we'll have more from our interview when we come back.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: Some of our stations are leaving us now, but we'll be right back with more FACE THE NATION. Stay with us.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: Welcome back to FACE THE NATION. We continue with our conversation with David Rubenstein.

(Begin VT)

JOHN DICKERSON: You've had success in public sector, private sector, philanthropy. Let's say you were thrust into the job. As the President, what do you think the hardest part of the job would be?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: I would want to surround myself with people who I thought had experience, who had the right motivations, were coming into public service because they wanted to help the country and not for any other purpose. I'd want to make sure I recognize that members of Congress are an equal branch of government and want to work cooperatively with them and also want to recognize that the Judiciary is an also an equal branch of government. And what it says also is a very important in terms of how the government is to be governed. But also the most important thing is persuading people to do things that you think are the right things to do. And you have persuade people by being honest with them, being forthright with them, bringing them along in a way I think makes people feel they are getting something from them-- from the negotiation. A good negotiation is one where both sides feel they are getting something. They are not completely happy with it, but they are getting something out of the-- out of it.

JOHN DICKERSON: How do you think Donald Trump has done on that front?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: Well, I think it's very difficult to judge a President this early, to be honest. I think most historians would say give me forty years after the presidency to evaluate whether the person has done a good or bad job.

JOHN DICKERSON: Given what you know about the presidency, when you hear it talked about in presidential campaigns, is there a part of that conversation that you say, you know, this is nice, but it's really not what the job is?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: Well, when you're running for President of United States, your job is to get elected to some extent and do so in a reasonably honorable way. You can't say things that are ridiculous, I think, but you should do so in a reasonably honorable way. But you have to-- to recognize that what people say in a campaign rarely can get implemented so easily. So if you say I want to have a certain type of tax, I want to change the law this way, it's not that easy to do. You have to deal with Congress. And so I think it would be a good idea if people were to propose things that are realistically possible and not-- not to ignore the impossibility of doing something great. But sometimes you have to have bold ideas and bold ideas are good, but sometimes some things are just not going to happen and you can get people excited about the prospect of it and you're really going to disappoint people.

JOHN DICKERSON: If you could give the American story to every presidential candidate, what lesson would you hope they draw from it?

DAVID RUBENSTEIN: I would say to all the presidential candidates, learn more about American history, learn about the things we've done right and wrong in the past. Do not think you have the sole knowledge of what's the right thing to do is and bring other people into the equation. Make sure you bring into the-- to your proposals about what you want to have done and what you're into your administration if you're elected. People that have a sense of history. Very often, many of our Presidents have met with historians because they want to learn what previous Presidents did. I think that's a good thing. And I think learning what our previous Presidents did, the good and bad, is a good way to-- to learn how to be a good President.

(End VT)

JOHN DICKERSON: Rubenstein's book was published by Simon & Schuster, a division of the CBS Corporation. The full interview is on our website facethenation.com.

We will be back in a moment with our book panel.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: We turn now to a conversation with four authors whose books focus on Presidents and patriotism in politics. Ruth Marcus is the author of a new book that looks at one party's mission to control the Supreme Court, "Supreme Ambition: Brett Kavanaugh and the Conservative Takeover." Michael Duffy is the co-author of "The Presidents Club: Inside the World's Most Exclusive Fraternity." Susan Page is the author of "The Matriarch: Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty" and the upcoming "Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Arc of Power." Our final panelist, Jon Meacham joins us from Nashville. His latest book is "The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels." It examines national divisions at critical times in our history. Jon, I am going to start with you. You wrote recently that this impeachment question tells us something larger. It's not just about a President, it tells us something about the country. So what are the stakes right now?

JON MEACHAM ("The Soul of America"/@jmeacham): All that at moments of enormous existential crisis over the direction of the country. Andrew Johnson and the verdict of the Civil War, where we're really going to up-- act on the implications of the victory of-- of the Union victory at Appomattox. President Nixon was coming with Vietnam, and-- and the questions about the nature of-- of the country. In many ways, in fact, I think we can think of the modern founding of the country as 1964, '65 with the Civil Rights Act. We've only governed this particular polity for fifty-five years or so, and-- and Vietnam and-- and that era was a period of enormous tension. And the Clinton era was in a way a precursor to this one, where we were returning to an eighteenth and nineteenth-century system of partisan media. It was to some extent, a-- a battle over generational power. And now we face this wildly unconventional President who is actively and overtly putting all the norms that so many of us were accustomed to on trial. And so we have these forces in American life that are perennial, xenophobia, extremism, racism, nativism, isolationism. They ebb and they flow in American life, they always have. And right now they are flowing, the task of the country is to get them to ebb.

JOHN DICKERSON: And, Ruth, what Jon describes and sets the table for there nicely, it feels like we had a bit of a preview of what we are going to see with impeachment hearing, which-- which is what you write about with the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation. Do you see those-- those parallels?

RUTH MARCUS (Washington Post/@RuthMarcus/ Supreme Ambition): Indeed. And I think they are disturbing parallels that mainly involve the reflexive and automatic and unrelenting partisanship of our time, that-- that Jon and others have referred to. Republicans complain that we can't take impeachment now seriously because Democrats were talking about impeaching the President even before he was sworn in. Correct. Republicans claim that we couldn't take the allegations against Justice Kavanaugh seriously because Democrats were out to get him from the start and these only arose at the last minute. Correct. But in both situations the question is well were there serious allegations, are there serious allegations in the case of impeachment against the target of Democratic ire, and are we capable of taking those allegations seriously or do we so automatically go to our corners that we are not capable of rising above partisanship? I think that's a really open and serious question.

JOHN DICKERSON: One, Michael, you wrote about--it's an extraordinary thing--Bill Clinton when he was going through this, called Richard Nixon. So the idea that-- that two Presidents across that period of time would have a conversation, I mean you-- you can't imagine Donald Trump calling Bill Clinton.

MICHAEL DUFFY (Washington Post/"The Presidents Club"): No. I think Clinton-- Clinton admired Nixon's just resilience, the fact that he gutted it out, and yeah-- the famous quote from the Clinton impeachment experience was we'll just have to win this. When it was clear that he had done whatever he had done, we're just going to have to win this. And I think he looked to Nixon and Nixon's experience as a model because Nixon fought right up until the time the smoking gun came out. And then, of course, his party abandoned him. Both men were survivors and both men fought like the Dickens to hold on to power until they-- you know, in-- in Nixon's case couldn't. One other thing about that relationship, it would fall to Clinton, of course, to eulogize Nixon in 1994 when he finally died, twenty years after he left office. And-- and Clinton's famous remark at the eulogy was, "May the days of judging Richard Nixon on just one, you-- you know, part of his life, be brought to a close," which, of course, was a benediction and a prayer for him and all Presidents.

JOHN DICKERSON: Right.

RUTH MARCUS: And are convenient, huh?

JOHN DICKERSON: Yes. He was making an appeal for the long sweeping view.

MICHAEL DUFFY: For-- and for all of the Presidents--

JOHN DICKERSON: Right. Right.

MICHAEL DUFFY: --who would afterwards come.

JOHN DICKERSON: Susan, I want to ask you about another part of this drama which has really struck me is that-- is during the-- the testimony from the House Intelligence Committee--

SUSAN PAGE (USA Today/@SusanPage): Mm-Hm.

JOHN DICKERSON: --a lot of the witnesses did not just start with the facts of the case. They, you know, in writing we talked-- you know, talk about going up--

SUSAN PAGE: Mm-Hm.

JOHN DICKERSON: --to thirty thousand feet, they talked about the role America plays in the world. They talked about their immigrant backgrounds. What did you make of that?

SUSAN PAGE: You know this was a-- the-- the impeachment hearings were in many ways, kind of, a dispiriting episode because-- both because of the allegations being made and because of the partisan response to them. But I had-- had-- I thought it was inspirational to hear from these witnesses, career public servants who started by talking about their immigrant backgrounds. Two of them immigrants, one of them the child of immigrants, families that had fled-- Nazi Germany had fled the Soviet Union, had come here for greater economic opportunity, loss of a class structure, and they talked about how grateful they were to America for taking them in, giving them this opportunity. And that was one reason they had chosen the path of service that they had. I thought that was-- I thought that was the best moment. It was a reminder of what Americans want to protect about our country, that seems often just so battered in these times.

JOHN DICKERSON: Right. In this room is not just the behavior of President, but-- but questions of bedrock basic American values--

SUSAN PAGE: Mm-Hm.

JOHN DICKERSON: --that everybody is also fighting over. Jon, I want to get your thoughts about the task before the House Judiciary Committee this week, which is to start looking at the Constitution and what guidance it gives for this inquiry. What wisdom-- wisdom do you think that the document or that summer in Philadelphia should give us in terms of thinking about this?

JON MEACHAM: The impeachment clause was added in part because George Mason of Virginia argued that, shall any man be above justice? That was the-- that was the central question. And the question that the framers tried to argue and-- and answer was that there had to be a check and a balance on the executive. The entire insight, remember, of the-- the guiding insight of the Constitution was that we would screw everything up. And we've done everything we can since then to prove them right. It's-- it's a fundamentally human document, and formed by a kind of Calvinistic insight that we would be driven by appetite, we would be driven by ambition, we were shaped by shortcoming and sin and, therefore, sovereignty had to be divided, power could not be-- all power could not be given to any one element in the republican, lowercase r, contract. And so impeachment was a hugely important element there. The article is very short. It's about treason, bribery, and other high crimes and misdemeanors. The latter phrase comes from the English common law. And as Gerald Ford, famously remarked, "a high crime and misdemeanor" is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives says it is at any given moment. And this generation, this group of members of Congress now has to face a genuine test, are they going to follow the facts or are they going to-- to use Ruth's phrase, are they going to reflexively be partisan and interpret reality not as they see it but as they wished to see it?

JOHN DICKERSON: Ruth, one of the things is that-- that we still don't know what the actual position is, because you can say, well, there are these acts but they don't raise to the level of-- of high crimes and misdemeanors, but the President is saying these acts--

RUTH MARCUS: Right.

JOHN DICKERSON: --weren't even bad in the first place. You've been studying the idea of originalism, the original public meaning of the Constitution. Does that give us any guidance here for how to interpret these mo-- this moment?

RUTH MARCUS: The-- the guidance is very Freudian in the sense that it is really a political question that is up to the political branch. But, yes, the framers were entirely worried about precisely the kind of event that we're talking about here, foreign influence, the misuse of presidential power for public gain and political advantage, rather than for the public good. If-- if you were going to-- the question that I would have for Republicans is, if this does not rise to the level of a high crime or misdemeanor or look a lot like the "Framers" conception of bribery, what does? And the-- the thing that I would say that gives me some concern here, I think the facts are so serious that the House was really constitutionally obliged to launch an impeachment inquiry, but we have now gone through three of these in our lifetimes, and impeachment was supposed to be and it should be a breaking case of emergency inquiry, and now I worry that we will unleash it as just-- just another political tool.

JOHN DICKERSON: And, Michael, it's happening in an election year which we haven't seen before.

MICHAEL DUFFY (Washington Post/The Presidents Club): No, it's always in the past happened in a second term, at least in-- in-- in our lifetime. So this allows the Republicans to argue, somewhat justifiably that, look, we're going to have an election in a year, just wait, you can make up your decision and let the people decide and they're deploying that almost, you know, daily or hourly. That raises another thing about John's test (ph) of Madisonian democracy. We're all hyper-dosing on this stuff. And-- and, you know, depending on whether you are like us and you have to drink it every day or you are-- you are just following along informally can seem at times that this is the worst that the country has ever faced, but I suspect it between a whole number of 1777, 1863, 1932. There have been other difficult times. What's different now is that how we experiencing it, that we are-- we're self-arming for division because so much of the information we get is coming to us through our devices and those devices are weaponized to sort of alienate and divide us, and that is a difference in-- in-- certainly between this and the last impeachment and all the ones that have come before. And I think this is-- this is the test that Madisonian democracy that, you know, we're meant to, you know, think-- have our better angels work at all levels here, but at every turn, we are being fed information that is-- divides us rather than brings us together and that is a real test of whether we can survive.

JOHN DICKERSON: And we're self-satisfying ourselves by-- by continuing to drink that ourselves. Susan, Michael just described the state of affairs. Nancy Pelosi didn't want to go down this impeachment road, felt like she had to. What-- what is the state of the Nancy Pelosi view of the world as she tries to hold on to power at a time that we're in, in this volatile moment?

SUSAN PAGE (USA Today/@SusanPage/The Matriarch): Well, this is very much what Nancy Pelosi predicted would happen when she was holding off some Democratic instincts to impeach the President months ago, years ago, since soon after his election, which is it would be divisive for the country and you shouldn't go forward unless you could get bipartisan support. But then you had the Ukraine phone call come out, and I think at that point she determined-- she decided that you had no option as Ruth was saying, if not this, what would be impeachable, had to go forward. She has tried to keep the focus narrowly on the Ukraine matter to keep the timetable going incredibly fast, the speed of this impeachment inquiry is really quite breathtaking, with the idea that we're going to see articles of impeachment perhaps this week, we're going to see a vote of the House before the end of the year, and then it goes to the Senate. And I think the instinct in the Senate is also let's do this and get it off our plate.

JOHN DICKERSON: Michael, before we go, I want to ask you about the 2020 election. I don't know whether when I worked with you or somebody when we were back at TIME Magazine said, every election is about one question, maybe they didn't say that but I'm going to-- what is the question of this election?

MICHAEL DUFFY: Well, all elections are about, you know, hope or fear, and whether you-- or-- or about change and whether you hope for change or fear it. I think at the moment this is provisionally will be is-- whatever they think about impeachment in a year, given what Amy said in the previous segment, this will be a referendum on Donald Trump, no question, and impeachment may play into that, both sides think it's going to help them. That's what's so interesting. The Democrats think they have to push this through, and have this test and show that they have done it in order to help build their support in their base. Republicans, I think increasingly think this will build our base as well and turn out the people who believe Donald Trump.

SUSAN PAGE: I-- I disagree. I think both parties think they hope it helps them.

MICHAEL DUFFY: Mm-Hm.

SUSAN PAGE: I think both parties fear it's going to hurt them. And I think at this point it is impossible to figure out exactly what the politics of this issue is going to be.

JOHN DICKERSON: Let me ask the final question to you, Jon Meacham. David Rubenstein suggested it takes forty years before you can weigh in on a President. What's your view on that and we should let people know that you weighed in on George Herbert Walker Bush before that timeline.

JON MEACHAM: Twenty-five-- Michael Beschloss, our friend says twenty-five years, and so I'm a Beschlossian on this important question. And I-- I think that's about right. Forty years is biblical, and so, therefore, we should be for it. But-- but I think twenty-five at least worked for me. And I would say, if I may, President Bush died a year ago yesterday, and when you think about however imperfect a man he was in-- in-- in-- in life and politics, we're all-- we all have our problems, but he really embodied a kind of public service that seems incredibly remote now. It's almost as though we're talking about Agincourt when we think about a man who-- a Republican President who signed the America's Disabilities Act and managed the-- the fall of the Berlin Wall with such grace and restraint. And I think that when we think about that everything is cataclysmic and we're always at the edge of a cliff, twenty-five years ago we had a President that's almost unimaginable now until, as he would put it, we imagine it again. And so, you know, the first election we had in this country that was about the soul of America was eighteen hundred, when Thomas Jefferson ran saying we needed a revolution to get back to 1776. So if they were talking that way then, it's not surprising that we're talking this way now.

JOHN DICKERSON: All right. Jon Meacham, thank you so much. And thanks to all of you for being with us.

We are going to ask Ruth to stick around for a few more minutes, and so you do that too.

We'll be right back.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: We're back with Ruth Marcus to talk more about her book, "Supreme Ambition: Brett Kavanaugh and the Conservative Takeover."

RUTH MARCUS: Hi.

JOHN DICKERSON: Welcome back, Ruth.

RUTH MARCUS: Thank you.

JOHN DICKERSON: So some people may think of this as what they saw through their television screen which were faces in a room with a bunch of senators, but you-- you sketch a story of Titanic forces in America. Bring some of those forces into the story to remind people of really all that's going on in this drama.

RUTH MARCUS: Sure. Well, as you say, this is not-- everybody was transfixed for a few weeks in the fall of 2018, but this is a story that stretches back decades, literally. This-- this is a thirty years war on behalf of Republicans and conservatives to finally cement a conservative majority on the Supreme Court. And that is the opportunity that they had with the resignation of Justice Anthony Kennedy and with the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh. And as the problems arose with the Kavanaugh nomination Republicans rallied around him, in part, because of some of the forces of partisanship that we've been talking about previously, but also because this was their moment to finally achieve this goal of thirty years, and Brett Kavanaugh was too big to fail. They were not going to allow him to do that. And so what I tell in the book, "Supreme Ambition," is the story of how everyone from the White House counsel who refused to take a phone call from the President, who was trying desperately to reach him, Don McGahn was worried that the President was going to tell him to yank the Kavanaugh nomination. He didn't want to hear it from him. He didn't want to take a call from the most powerful man in the America. He told his deputy I don't talk to quitters. It's a story of how the FBI and senators, Republican and Democrat, refused to pursue leads that might have jeopardized the Kavanaugh nomination, and it's the story of what the implications are of this nomination for our country, because long after we're done with impeachment and long after the 2020 election, Donald Trump's legacy is going to be-- the judges that he put on the federal courts and on the Supreme Court and it is going to be the triumph of conservatives which explains why they have stuck with him for so long.

JOHN DICKERSON: And that's a thirty to forty years, depending on the lifespan of the judges, thirty to four-- year impact on American life, not four or eight years of a presidency.

RUTH MARCUS: No, it is a long time and Donald Trump has been going around and boasting about how he's-- his judges are younger than Obama judges, they're going to be around for a while.

JOHN DICKERSON: Let's talk about Don McGahn, the White House counsel, really interesting. You just-- you just talked about an act of insubordination. There's been a lot of talk about when and when-- a staffer can and can't be insubordinate. He is perhaps-- and you tell me what you think-- the most powerful and beneficial advisor the President has. Wouldn't-- maybe have gotten elected without him.

RUTH MARCUS: So a couple of things. Right here in this very building at the Jones Day law firm, Don McGahn helped to orchestrate the thing that probably, among everything else, helped Donald Trump get elected President, which was creating a list of Supreme Court nominees, not a-- not a surprise to have a shortlist, hugely Trumpian and never done before to have a list that was made public. Guess who was not on that list? Brett Kavanaugh. But--

JOHN DICKERSON: Made public during the campaign.

RUTH MARCUS: Made public during the campaign and Brett Kavanaugh managed with the help of his friends, including Justice Kennedy to make his way on to that list, and with the help of Don McGahn, who was a fascinating figure, the most consequential White House counsel in history, both Donald Trump's greatest help in terms this lega-- helping to build the legacy, along with the Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell that will outlast this President and that he will be proudest of in the long run, but also in the Mueller investigation and we still see conversations about will-- whether we'll ever get his testimony on that, the President's greatest problem, because he testified and basically created the elements of the obstruction case against the President with Mueller.

JOHN DICKERSON: Fifteen seconds, the reason the list was so important, is it showed conservatives that Donald Trump was--

RUTH MARCUS: A-- somebody who they could trust and to be taken seriously and that he would achieve what Republican Presidents before him had not managed to achieve and had squandered.

JOHN DICKERSON: Mitch McConnell thinks that's why he's President.

RUTH MARCUS: Indeed.

JOHN DICKERSON: Ruth Marcus, thanks so much. It's a great book. "Supreme Ambition" is out Tuesday. It was published by Simon and Schuster, a division of the CBS Corporation.

We'll be right back.

(ANNOUNCEMENTS)

JOHN DICKERSON: That's it for us today. Thanks for watching. And thank you to the Jones Day law firm for the facilities here on Capitol Hill. Margaret will be back next week. For FACE THE NATION, I'm John Dickerson.