FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried's rise and fall at center of new Michael Lewis book "Going Infinite"

Michael Lewis has made a literary career finding jump-off-the-page characters, and using them to help tell complicated stories. And what could be more complicated than explaining cryptocurrency? Lewis gained all-hours access to Sam Bankman-Fried, known for a time, as the J.P. Morgan of crypto. His sector as ungoverned as his hair, Bankman-Fried was worth more than $20 billion before he turned 30…an unlikely celebrity, his life braided finance, politics, sports and pop culture. Then the empire crumbled and today, Bankman-Fried sits in jail on various federal charges and faces potential sentences of more than 100 years. Lewis, though, didn't panic-sell. He simply went where the story took him. His latest book, "Going Infinite" comes out Tuesday…. which is also the opening day in the trial of Sam Bankman-Fried.

Jon Wertheim: You had so much access to Sam Bankman-Fried writing this book. What ultimately is-- is the purpose here?

Michael Lewis: I realized I had an ambition for the book. I saw it as kind of letter to the jury. I mean there's gonna be this trial. And the lawyers are gonna tell two stories. And so-- there's a story war going on in the courtroom. And I think neither one of those stories is as good as the story I have.

Michael Lewis didn't set out to write this book. Two autumns ago, he was at home in the Bay Area when he got a call from a friend, interested in investing with a young billionaire. Could Lewis meet with this wunderkind and size him up ….So it was, Lewis brought Sam Bankman-Fried here, in the Berkeley Hills, for a hike in the park.

Michael Lewis: You gotta remember, I knew nothing about him. I-- all I knew was I was supposed to evaluate his character. And that 18 months earlier, he had nothing, now he had $22.5 billion dollars and was the richest person in the world under 30.

He didn't care much about like, spending it all on yachts, he was gonna spend it to save humanity from extinction kind of thing. So the whole walk was, like, my jaw was on the floor about here, after I heard all that.

Jon Wertheim: As an author, whose stock in trade is finding interesting characters, is your-- your story meter startin' to beep about now?

Michael Lewis: Oh, I was on red alert. And I said this to him, I said, s-- "I don't know what's gonna happen to you. Something's gonna happen to you. Can I just come and, you know, ride shotgun.

Michael Lewis: Now, riding shotgun ended up being, like, hanging on for dear life to-- you know, an automobile that's goin' 270 miles an hour, and taking every hairpin turn.

Sam Bankman-Fried and Lewis would end up meeting more than a hundred times over two years, speaking for countless hours.

As our camera rolled in July, note how Bankman-Fried shuffled cards and jackhammered his legs and avoided eye contact. Lewis considers Bankman-Fried the most challenging —and fascinating —character he's ever encountered. this from an author who's been writing non-fiction since the eighties.

Michael Lewis: The story of Sam's life is people not understanding him. Misreading him. He's so different, he's so unusual. I mean, I think in a funny way that the reason I have such a compelling story is I have a character that I do come to know, and that the reader comes to know, that the world still doesn't know.

A graduate of MIT, Bankman-Fried saw the world in numbers, framing everything in his life as a probability exercise, including philanthropy. He committed to making as much money as possible… so he could give it away as efficiently as possible…guided by a social movement, effective altruism.

Michael Lewis: What it means in Sam's instance is you can go out and have a career where you do good. You can go be a doctor in Africa. Or you can go out and make as much money as possible and pay people to be doctors in Africa. If you're a doctor in Africa, you get-- you end up saving a certain number of lives, but you're only one doctor. But if you can pay 40 people to become doctors in Africa, you're gonna s-- you're gonna save 40 m-- 40 times the number of lives.

Jon Wertheim: This is like a strategy game.

Michael Lewis: Well, you don't understand Sam Bankman-Fried unless you understand that he turns everything into a game. Everything is gamified.

Bankman-Fried worked as a Wall Street trader before moving to Berkeley at age 25 to start his own trading firm, Alameda Research. Instead of buying and selling stocks or bonds, he would traffic in crypto, a digital form of currency not tied to a centralized system.

Michael Lewis: The basic idea was to be the smartest person in the crypto markets, to be the one who did the kind of trading in crypto that the smartest Wall Street traders did in stocks.

Jon Wertheim: So these quant skills he had as a trader on regular stocks and equities markets, he was gonna bring to this new ascending crypto world.

Michael Lewis: Correct.

Jon Wertheim: What's the difference between crypto finance and traditional finance?

Michael Lewis: Well, the promise of crypto finance is the promise of an absence of intermediaries. If I want to wire you $10,000, a bank has to do it. A bank records the transaction. A bank takes some little slice of it. If I want to wire you $10,000 worth of Bitcoin, I could just hit a button and you get it. So you remove the institutions.

Coming out of the 2008 financial crisis, crypto took hold as an anti-establishment, punk rock version of a financial system... which Lewis finds ironic….

Michael Lewis: In the beginning, especially, it's a crowd of people who are incredibly mistrustful of institutions. What attracts them to it is they hate the government. They hate banks. But then they somehow-- this pool of incredibly mistrustful people proceed to trust each other in ways that I wouldn't trust you.

Jon Wertheim: They're parking their money in a sector that's unregulated. There are no physical properties.

Michael Lewis: Provably--

Jon Wertheim: You don't go in there.

Michael Lewis: --squirrelly and unreliable–

Jon Wertheim: Right--

Michael Lewis: --over and over.

Jon Wertheim: But it's predicated on trust.

Michael Lewis: It's like they are Charlie Brown kicking the football, that they're sure that this time Lucy's gonna hold it.

Still, Bankman-Fried made a fortune at Alameda Research. And then he really got rich. Instead of simply trading, Bankman-Fried seized on the idea of opening his own cryptocurrency exchange.

Michael Lewis: One of the things he notices is that all the crypto exchanges are screwed up in one way or another. There are dozens of these places where you can trade crypto, but they are– they're not structured for a professional trader. The technology is bad. They'll lose their customers' money. It's the wild west. He realizes that if you built a better exchange-- he wanted to build an exchange he could trade on. So he creates FTX. And once he created it, it went boom. And when it went boom, he realized that, "Well, that's– ya know– that's the goldmine." It actually isn't trading the crypto.

Jon Wertheim: This is owning the casino.

Michael Lewis: It's owning--

Jon Wertheim: Right?

Michael Lewis: --the casino. He started as a gambler and he realized that, you know, building the better casino was actually gonna be more valuable.

Soon, roughly $15 billion a day in trades—were executed on his new exchange, FTX.

Michael Lewis: If you're sitting in the middle of those transactions and you're taking out even a tiny fraction of a percentage point, there's a lot of money to be made.

Jon Wertheim: Indifferent to the outcome of the trade, he's just–

Michael Lewis: You're taking no risk, you're taking no risk at all. It didn't matter to him, whether crypto went up or crypto went down; as long as people were trading crypto, it made money. It's the best business. I had one venture capitalist tell me that several of the venture capitalists thought that Sam might be the world's first trillionaire.

Jon Wertheim: Trillionaire?

Michael Lewis: Yeah. They're looking for the next Google. They're looking for the next Apple. They thought FTX had that kind of possibility, that it had a chance to be the single most important financial institution in the world.

As he began accumulating billions as if they were Pokemon cards, Bankman-Fried began attracting something else he wasn't accustomed to: attention.

Michael Lewis: He changed not at all. You know, he'd never been on TV. He goes on TV in his cargo shorts and his messy hair and he's playing video games while he's on the air.

Jon Wertheim: Wait. Wait. He's played video games on the air?

Michael Lewis: You would think your first television appearance, you might be a little-- (laughs) a lit-- a little uptight, a little nervous. And if you watch the clip you can see his eyes going back and forth, back (laughs) and forth. It's because he's trying to win his video game at the same time he's on the air.

Whether it was his smarts, his fierce indifference to appearance or simply his vast wealth…the beautiful people suddenly found him irresistible…

Jon Wertheim: As his net worth goes up, so does his social capital. (laughs) You write about a-- Zoom meeting you walked in on.

Michael Lewis: He says, "I gotta go do a Zoom." I said, "What is it?" And he says, "There's this person named Anna Wintour. And-- and I--" he didn't know who she was.

Jon Wertheim: He had no idea who she was?

Michael Lewis: No. So I sat off to one side where she couldn't see me. And I watched this Zoom.

Jon Wertheim: Now, you're thinking, "What does Anna Wintour want to do with a schlub like Sam?"

Michael Lewis: Well—exactly. He is the worst-dressed person in America. He is the worst-dressed billionaire in the history of billionaires. And what she wants him to do is to sponsor the Met Gala, (laughs) her great ball that she throws every year, which is, like, you know, all about dress, and appearances. Sam was a social experiment. He is person who has nothing, all of a sudden has a seemingly infinite dollars, will give it away, is unbelievably open-handed about it, and doesn't ask a whole lot of questions. What that attracts, who shows up when that-- when this person exists? Everybody.

Jon Wertheim: Everyone comes with a trough to--

Michael Lewis: Everybody comes to the trough. Everybody is-- (laughs) wants to be his best friend.

Bankman-Fried wanted it known that FTX was the go-to player in crypto.

He turned to the sports world to bring his exchange both legitimacy and edge. Lewis saw the FTX internal marketing documents…

Michael Lewis: He paid Tom Brady $55 million for 20 hours a year for three years. He paid Steph Curry $35 million for-- same thing for three years.

Jon Wertheim: Pretty good hourly wage.

Michael Lewis: He spent 100 and something million dollars, buying the naming rights for the Miami Heat arena.

Michael Lewis: (laughs) For which he then paid Larry David another $10 million, you know. It's breathtaking, what's on that list.

Jon Wertheim: Did any of the people surrounding him, these celebrities, do it 'cause they found him interesting or was it all because he's worth $20 some billion dollars?

Michael Lewis: It's probably not fair for me to speak for them, but I will speak for them. Tom Brady, I think, adored him.

Jon Wertheim: Really?

Michael Lewis: I think Tom Brady thought he was just a really interesting person. I think he liked to hear what he had to say.

Michael Lewis: And he really liked Tom Brady. And Sam wasn't, like, a big sports person. So it was funny to watch that interaction. It was like, "These two people actually get along." It's like the class nerd and the quarterback--

Jon Wertheim: The two high school tribes--

Michael Lewis: Yeah. Yeah. No. The nerd of all nerds. (laughs) Like, even the nerds don't hang out with this nerd, he's such a nerd. (laughs) The quarterback somehow likes him. And he somehow likes the quarterback.

Lewis writes in his book that Bankman-Bried's philanthropic ambitions kept pace with his wealth. Never mind doctors in Africa, he set out to confront what he saw as existential threats to all of humanity.

Michael Lewis: Sam Bankman-Fried ends up with a portfolio heavily concentrated in two things. Pandemic prevention, because there really are things the government should be doing. And the other thing that made his list that was so interesting was Donald Trump. He took the view that all the big existential problems are gonna require the United States government to be involved to solve 'em. And if the democracy is undermined, it-- like, we don't have our democracy anymore, all these problems are less likely to be solved. And he saw Trump trying to undermine the democracy, and he thought, "Trump is-- belongs on the list of existential risks."

To that end, Lewis writes that in 2022 Bankman-Fried met with the most unlikely of allies, Republican Senate Minority Leader, Mitch McConnell …

Jon Wertheim: You're flying with Sam and he tells you about a meeting he's gonna have with Mitch McConnell.

Michael Lewis: Well, the interesting thing starts before we even get on the plane. I meet him at the airport, and he comes tumbling out of a car. And he's in his cargo shorts and his T-shirt. And he's got, balled up in his hand-- it takes me a while to see what it is, but it's a blue suit. It's got more wrinkles than any blue suit ever had. It's been just jammed into this little ball. (laughs) And a shoe, like, falls out of the pile that he's got in his arms. And I said, like, "What-- why you have the suit?" And he says-- (laughs) he says, "Mi-- Mitch McConnell really cares what you wear when you-- (laughs) when you meet with him." And he's having dinner in six hours with Mitch McConnell. And I-- I said, "Well, you got the suit. Is there-- you got a belt?" He goes, "No. I don't have a belt." I said, "You got-- you have a shirt?" He goes, "No. No shirt," "and the suit, you really can't really wear-- (laughs) wear that suit." And he goes, "Yeah. But they told me to bring a suit."

According to Lewis, Bankman-Fried wanted to help McConnell fund Republican candidates at odds with Donald Trump…

Michael Lewis: What is the subtext of this dinner, is Sam is gonna write tens of millions of dollars of checks to a super PAC that Mitch McConnell is then gonna use to get elected people who are not hostile to democracy.

Jon Wertheim: Wait. So, Mitch McConnell has a list of Republican candidates who are, sort of, on the playing field for democracy versus what he deemed outside?

Michael Lewis: He and his people had done work to distinguish between actual deep Trumpers and people who were just seeming to, to approve of Donald Trump, but were actually willing to govern.

Bankman-Fried ended up giving multi-millions in support of Republican candidates. Back in 2020, Bankman-Fried had ranked among Joe Biden's biggest donors. As 2024 approached, he planned on spending more, albeit in the most unconventional way…

Jon Wertheim: One of the most shocking passages in this book, I thought, came with this revelation that Sam had looked into paying Donald Trump not to run.

Michael Lewis: That only shocks you if you don't know Sam. (laughs) Sam's thinking, "We could pay Donald Trump not to run for president. Like, how much would it take?"

Jon Wertheim: Did he get an answer?

Michael Lewis: So he did get an answer. He was floated-- there was a number that was kicking around. And the number that was kicking around when I was talking to Sam about this was $5 billion, Sam was not sure that number came directly from Trump.

Jon Wertheim: Wait. Wait. So-- so Sam's looking into paying Trump not to run. And he actually gets– might not have come from Trump himself, but he actually got a price?

Michael Lewis: He got one answer, yes. The question Sam had was not just, "Is $5 billion enough to pay Trump not to run," but "Was it legal?"

Jon Wertheim: Why didn't this happen? Why didn't he follow through?

Michael Lewis: Well, they were still having these conversations when FTX blew up. So why didn't it happen? He didn't have $5 billion anymore.

Approached for comment by 60 Minutes, neither former President Trump nor Sen. McConnell responded…last November, in a matter of days, megabillionaire Sam Bankman-Fried lost virtually everything, and he soon faced an onslaught of federal fraud charges…

Meteoric as the rise of Sam Bankman-Fried was, the fall came faster still. In a span of days, a celebrity multi-billionaire became a pariah, his wealth largely evaporated, as federal prosecutors mounted a case against him. In his new book, out this week, Michael Lewis details the crash, and leaves it to readers to decide if Sam Bankman-Fried was a cryptocurrency conman in cargo shorts….or a really smart guy, singularly ill-equipped to run and manage a business.

By spring of 2022, Sam Bankman-Fried had planted his flag in the Bahamas. He decided to move his high-flying cryptocurrency exchange, FTX, to the islands, not for the beaches, but for the friendly regulatory climate. With the prime minister on hand, they put shovels in the ground for a new headquarters. Bankman-Fried openly discussed paying off the country's $9 billion national debt. By this point, Michael Lewis and Bankman-Fried had a dynamic that went beyond author-subject.

Michael Lewis: And he started using me as a sounding board.

Jon Wertheim: For what?

Michael Lewis: For just, like, decisions he was making. Should I join Elon Musk in buying Twitter? You know? Should we do this? Should we do that?

Jon Wertheim: What'd you tell him?

Michael Lewis: Mostly, my answers were no, no, (laughs) and no. And he would look at me and say (laughs), "You're a boring grownup."

And Bankman-Fried, now 31, told Lewis, now 62, that anyone older than 45 was useless… but Lewis noted that if ever there were a corporate leader in need of adult input to manage 400 employees, it was Sam Bankman-Fried….

Jon Wertheim: What kind of a manager was he?

Michael Lewis: Horrible. I mean, even his best friends-- inside the company said, "Sam is just not built to manage people."

Jon Wertheim: Had Sam managed anything before?

Michael Lewis: His sole experience of leadership was running puzzle hunts for math nerds out of high school. And actually thought deep down, if ya asked him, people shouldn't need to be managed. So he proceeded to act on that and basically didn't manage them.

Jon Wertheim: Is there any checks and balances happening in this environment then?

Michael Lewis: Well, what checks and balances would you imagine there might be in a corporation?

Jon Wertheim: Chief financial officer?

Michael Lewis: No. There's no chief financial officer.

Jon Wertheim: HR department?

Michael Lewis: No, there was no HR department.

Jon Wertheim: Compliance office?

Michael Lewis: N-- oh no. There-- no. There was no board of directors. Or, rather, I asked Sam, I said, (laughs) "Who's your board of directors?" And he said, "We don't really have one." I said, "What do you mean, you don't have one? Everyone has one." He says, "There are two other people on something called a board of directors, but it's changed and I don't even know their names. And their job is just to DocuSign whatever--"

Jon Wertheim: He didn't know the names of the board of directors?

Michael Lewis: (laughs) No, he didn't know who was on it.

Jon Wertheim: So he's running this like a lemonade stand, and he's doing enough volume of business this-- this could be a public traded company if he wanted to.

Michael Lewis: Oh, no. If it was a publicly traded company, it'd be a publicly traded company worth $40 billion. No, it was all Sam's world. And there was nobody (laughs) there to say, like, "Don't-- don't do that."

FTX purchased a $30 million executive penthouse in a Bahamas resort—flush with an exclusive marina. It was lost on Sam, who worked feverishly in the office, and slept on a beanbag chair. But there was another reason he avoided the luxe penthouse: his girlfriend Caroline Ellison, a former Wall Street trader herself, had kicked him out. Compounding matters, he had put her in charge of running Alameda Research, Bankman-Fried's privately held trading firm.

Jon Wertheim: So the romance between Sam and Caroline goes sideways. How does that impact what happens to FTX and Alameda Research?

Michael Lewis: Coincidentally, the romance more than goes sideways. They have a falling out where they're basically not speaking to each other. She's not speaking to him-- at precisely the time crypto collapses.

Jon Wertheim: Explain why that's a problem.

Michael Lewis: It's a problem because Alameda Research is one of the traders on FTX.

Translation: though Bankman-Fried owned the FTX exchange, he was also trading crypto on FTX through his other business, Alameda Research.

Michael Lewis: And he was gambling in his own casino. And it, it created conflicts of interest.

Jon Wertheim: So he owns the casino, but he's still gambling?

Michael Lewis: Yes. He didn't stop gambling.

The value of crypto had been eroding throughout the summer of 2022. Then came a one-two punch: a leak of Alameda's unflattering balance sheet in early november ... .and days later, Changpeng Shao, head of a rival exchange took to Twitter to question FTX's viability… this triggered a classic panic run—digital style— on FTX

Jon Wertheim: How fast was money flowing out of FTX?

Michael Lewis: In the run, you know, $1 billion a day was leaving, and–

Jon Wertheim: $1 billion a day this thing's gushing.

Michael Lewis: Yes. It unravels because the depositors at FTX want their money back. And it's not all there.

It wasn't all there in large part because the investors' money intended for FTX had wound up in Bankman-Fried's privately held fund, Alameda Research…. more than $8 billion…

Jon Wertheim: Do you think he knowingly stole customers' money, Sam?

Michael Lewis: Put that way, no. So there's another side of this. In the very beginning, if you were a crypto trader who wanted to trade on FTX and wanted to send dollars or yen or euros onto the exchange so you could buy crypto, y-- FTX couldn't get bank accounts. So Alameda Research, which could get bank accounts, created bank accounts for people to send money into so that it would go to FTX. But it was held in Alameda Research, Alameda Research bank accounts. And $8 billion-something piles up inside of Ala– Alameda Research that belongs to FTX customers that never gets moved--

Jon Wertheim: It never gets transferred over?

Michael Lewis: Never gets transferred.

Jon Wertheim: That sounds like a problem.

Michael Lewis: It's a huge problem.

Jon Wertheim: What's the toughest question you think Sam's gonna have to answer?

Michael Lewis: How do you not know that $8 billion that's not yours is in your private fund? I mean, really, how do you not know? Explain. $8 billion is in your private fund, that belongs to other people, and you're saying you didn't know. Please explain how that's possible.

Jon Wertheim: Did you do that?

Michael Lewis: Yeah. I did.

Jon Wertheim: What'd he say?

Michael Lewis: He said, "You have to understand that when it went in there, it was a rounding error, that it felt like we had infinity dollars in there, that I wasn't even thinking about it."

Jon Wertheim: I can see people watching this saying, like, 'Come on guys. This is like Elizabeth Holmes in cargo shorts. And this is all a ruse. Don't fall for the shtick. This is a bad actor.'

Michael Lewis: It's a little different supplying, you know, phony medical information to people that might kill them. And in this case, what you're doing is possibly losing some money that belonged to crypto speculators in the Bahamas. On the other hand, this is not to excuse. He shouldn't have done that.

Early in the morning of November 11th, Sam Bankman-Fried reluctantly docu-signed FTX into bankruptcy…it had taken five days for FTX to implode…

Jon Wertheim: You go back to the Bahamas as Pompeii is falling. What'd you see when you landed?

Michael Lewis: I got back the day, on the Friday of the collapse. It was the afternoon that Sam had signed the bankruptcy papers. And by then there'd been a mass exodus. Most of the employees had fled. And fled in such a way that-- kind of in a ridiculous way. They'd taken the comp–company cars and ditched them at the airport with the keys inside. Or they were–

Jon Wertheim: Just get the hell out.

Michael Lewis: Nobody knew what had happened. But they were just scared that they were gonna be detained by the local authorities. We drove into the lot, and Sam Bankman-Fried is walking loops around the parking lot. He had been brought over there earlier to be interviewed by Bahamas authorities. And nobody had given him a ride home. And he was just sitting there all alone.

Jon Wertheim: How do you divorce Michael Lewis, the empathetic human being, from Michael Lewis, the journalist and author, who recognizes what a third act this is? Pretty dramatic, right?

Michael Lewis: If I were a better person, I would have been deeply distressed by all of this. It took about a nanosecond before I thought, "Oh my God. This is an incredible story."

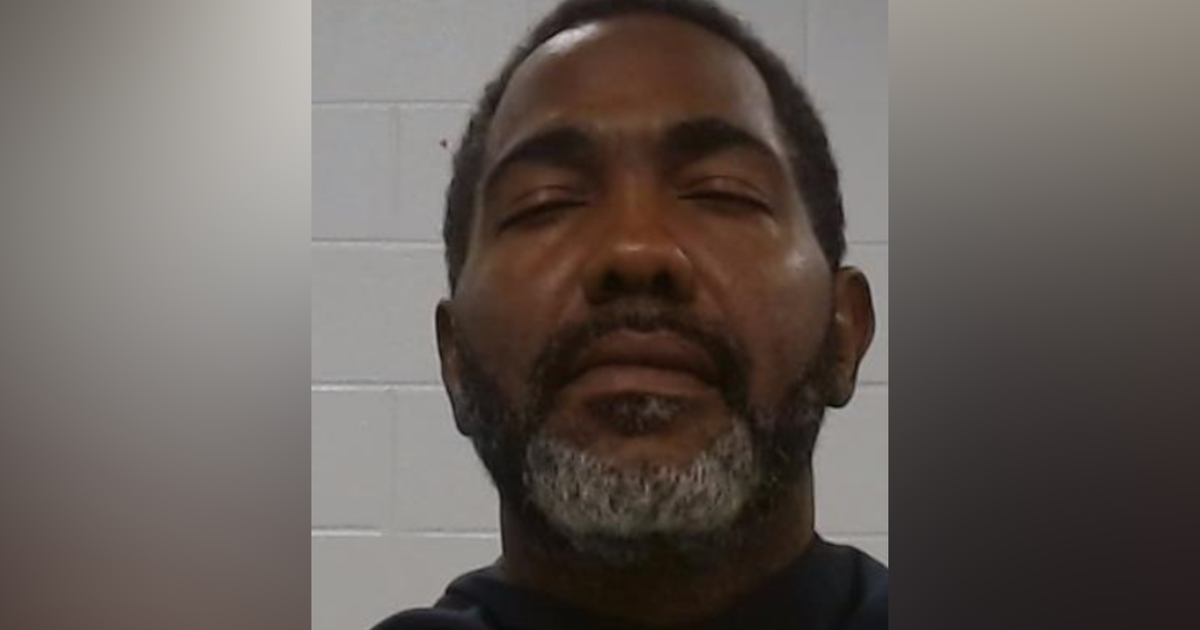

A month later, Bankman-Fried was arrested in the Bahamas and extradited to New York to face federal charges that he had fraudulently used customer deposits to finance billions of dollars of venture capital investments, real estate purchases, and political donations…

Jon Wertheim: What's your response to someone who hears this and says-- "It's-- it's a fun story, and it's crypto in the Bahamas, but this is the oldest architecture of a financial collapse that's been going on for centuries."

Michael Lewis: This isn't a Ponzi scheme. Like, when you think of a Ponzi scheme, I don't know, Bernie Madoff, the problem is-- there's no real business there. The dollar coming in is being used to pay the dollar going out. And in this case, they actually had-- a great real business. If no one had ever cast aspersions on the business, if there hadn't been a run on customer deposits, they'd still be sitting there making tons of money.

Inside the Beltway, in the Hollywood Hills and in sports arenas, suddenly (if predictably), it was: Sam Bankman who?….

Michael Lewis: He becomes toxic. Like, nobody wants to talk to him. He has no friends. You wa–watch everybody who rushed in rush out.

Jon Wertheim: How'd Tom Brady react to this?

Michael Lewis: The first reaction was very s-- it was sadness. He clearly really liked him. And he really liked the hope that he brought. I mean, a lot of people wanted there to be a Sam, you know? There is still a Sam-Bankman-Fried-shaped hole in the world that now needs filling. Like that character would be very useful to have--

Jon Wertheim: What he represented.

Michael Lewis: What he wanted to do with the resources. And Brady was I think crushed. And I think as time has gone by, and he's ceased to get a really good explanation about what's happened-- I think he's just like, "He tricked me. I'm angry. I don't wanna have anything to do with it anymore."

Starting in December, Lewis began driving the 45 miles from Berkeley to Stanford, where Bankman-Fried was living with his parents, who have also been ensnared in legal proceedings tied to FTX…. out on bail but wearing an ankle monitor, he left the door open for Lewis, so they could continue their conversations. We anticipated speaking with Bankman-Fried in August, but the judge in his case instituted a gag order, and then put him in a Brooklyn jail for violating terms of his release. Bankman-fried has pled not guilty…

Michael Lewis: He genuinely thinks he's innocent. I can tell you his state of mind four or five months ago. It's like, "If you offered me plead guilty and do six months of house arrest, I'd still say no."

Jon Wertheim: What do you suspect his biggest fear is if he has to go to prison?

Michael Lewis: Not having the internet. Now that sounds crazy, but I do think that if he had the internet, he could survive jail forever. Without having a constant stream of information to react to-- I think he may go mad. If you gave Sam Bankman-Fried a choice (this is quite serious) of living in a $39 million penthouse in the Bahamas without the internet, or the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn with the internet, there's no question in my mind he'd take the jail.

Michael Lewis has never before written something that dovetails so dramatically with a sensationalized news event. Lewis' book, "Going Infinite," comes out Tuesday, the same day Sam Bankman-Fried's trial begins.

Jon Wertheim: He made a mockery of crypto in the eyes of many. He's sort of taken away the credibility of effective altruism. How do you see him?

Michael Lewis: Everything you say is just true. And it–and it's more interesting than that. Every cause he sought to serve, he damaged. Every cause he sought to fight, he helped. He was a person who set out in life to maximize the consequences of his actions-- never mind the intent. And he had exactly the opposite effects of the ones he set out to have. So it looks to me like his life is a cruel joke.

Produced by Draggan Mihailovich. Associate producer, Emily Cameron. Broadcast associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Warren Lustig.