From the archives: 60 Minutes' first Pelican Bay report

This week on 60 Minutes, special contributor Oprah Winfrey reported from Pelican Bay, the notorious state penitentiary in California. The prison is known for its security housing unit, or SHU, which was designed to isolate prisoners. But when Winfrey visited, she found a reform movement that has significantly reduced the use of solitary confinement. The prison's SHU now holds many fewer inmates than it did just a few years ago.

60 Minutes first visited Pelican Bay in 1993. A look back at that story shows how much things have changed — and what hasn't.

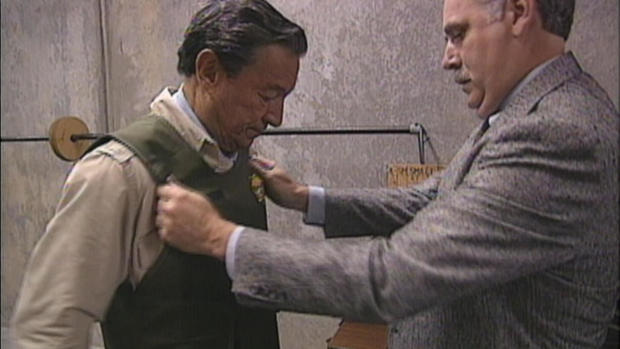

As correspondent Mike Wallace discovered, the California prison's reputation was already well-established. Convicts knew it as "Skeleton Bay," and they feared being sent to the SHU, the toughest maximum-security prison in the country.

"[T]o the men who are locked up there, especially in its SHU, Pelican Bay is simply torture, a living hell where inmates are brutalized and sometimes driven insane," Wallace said in the 60 Minutes story in the video player above.

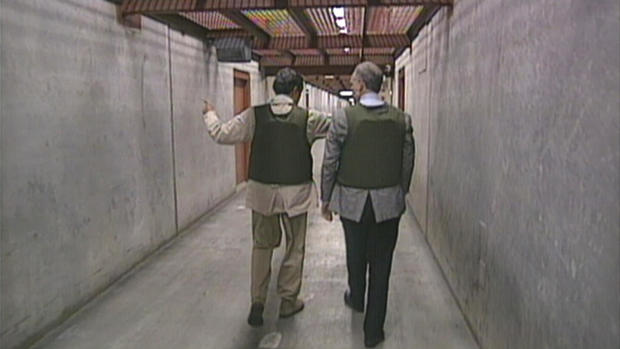

At the time, security risks prevented Wallace from stepping inside a SHU pod, a small, self-contained unit of eight cells where prisoners were held. Today, the pods are being emptied and, in some cases, converted into minimum security units. Winfrey was allowed to tour one of the still-occupied pods and speak to inmates.

At Pelican Bay, solitary confinement has always been used for offenses inmates commit once they are in prison, regardless of the crime they committed on the outside. The accommodations also haven't changed since 60 Minutes' first visit — SHU inmates are kept inside their cells for 22½ hours a day, with no direct sunlight and no direct contact with other inmates.

As Wallace explained, prisons across the country had embraced this isolating design as a tool to combat prison violence. "The state of California that runs it proudly proclaims it's the wave of the future, designed to isolate prisoners who, they insist, are out of control — too violent, too unpredictable to be housed with the run-of-the-mill murderers and rapists," he said.

But as Wallace discovered just four years after Pelican Bay opened, controversy over abuses in the SHU were growing, with inmates alleging they were being physically brutalized and driven insane. Dr. Stuart Grassian, then a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and expert on the effects of solitary confinement, had interviewed dozens of inmates in the Pelican Bay SHU. He told Wallace that more than a third of the SHU inmates were psychotic.

"Many of these people have minimal brain damage," Dr. Grassian said. "Many would do extremely well with anti-convulsive medications, mood-stabilizing medications, lithium… But instead, once they're in that criminal justice system, their behavior is viewed as criminal behavior to be punished."

Some inmates who hadn't exhibited mental health issues prior to incarceration developed them after time in the SHU. Wallace spoke with one inmate who attempted suicide. Another suffered a psychotic break. The latter inmate, Vaughn Dortch, had no prior history of mental illness, and following the incident, corrections staff placed him in a scalding hot bath, where he received third-degree burns. He had to be rushed to the hospital to undergo skin grafts.

"How do we justify this?" Dortch asked Wallace. "What am I locked up for, petty theft? I mean, do we put thieves on death row?"

Twenty-five years later, Winfrey has found a change in perspective from the man who currently runs the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Scott Kernan. She asks him if he believes solitary confinement "drives men mad" — and he agrees that it does.

"That was a policy that was intended to save lives and make prisons safer across the system," Kernan says. "It was a mistake, in retrospect, as we look back."

Pressure for change began to build in 2011, when Pelican Bay SHU inmates organized a series of hunger strikes. They also filed a class-action lawsuit challenging the use of solitary confinement.

The named plaintiff in that lawsuit, Ashker v. Governor of California, is inmate Todd Ashker. He spoke with Wallace in 1993 and went on to become an activist who played a central role in bringing reform to California's use of solitary confinement.

Ashker was held in solitary at Pelican Bay for more than 20 years after that interview with Wallace. He was released from the SHU under the terms of a settlement of his own lawsuit, and he is now a prisoner at Salinas Valley State Prison. 60 Minutes was unable to interview him again because he is currently in "administrative segregation" for violations of prison rules and regulations.

More than 90 percent of inmates held in California state prisons – including those in the SHU – eventually complete their sentences and are released back into society. Kernan now says the prison system's focus should be rehabilitation.

"When I first came in, that person was the enemy," Kernan says. "Now, 35 years later, I don't view the inmates as my enemy. They're people They're all coming out to be our neighbors. Why wouldn't we spend the resources and create an environment where when they come out, they're better people than when they got here?"