From the archive: John Lewis and the bridge

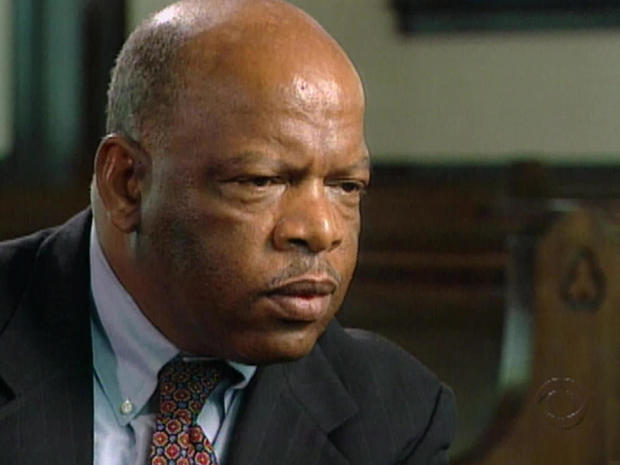

Rep. John Lewis died on Friday, July 17 at the age of 80. Back in 1998, "Sunday Morning" correspondent Rita Braver joined Congressman Lewis as he returned to the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma, Alabama, scene of one of the landmark confrontations of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Braver describes Lewis as "one of the most inspirational people" she has ever met. This story, originally broadcast on June 28, 1998, shows why …

"When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something, to do something," Rep. John Lewis said.

Watching Congressman Lewis at work on Capitol Hill, it was hard to believe that he grew up achingly poor in rural and segregated Alabama.

"I saw those signs that said 'white men,' 'colored men,'" he recalled. "You saw the water fountain marked 'colored,' a water fountain marked 'white.' I saw 'white waiting,' 'colored waiting.'"

Rita Braver asked, "As a child, did this make you feel angry? Did it make you feel sad or embarrassed?"

"As a child, I felt angry. I wanted to check a book out of a library, a public library, and I was told that black people could not check books out. So, I couldn't use the public library. And all of this just made me more and more determined to get an education, and to find a way to change the system and find a way to get out."

And indeed, Lewis did change the system. And though it took years for many Americans to learn his name, John Lewis was one of the key leaders of the civil rights movement. "I had been deeply inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.," he said, "and I wanted to get involved."

So, at 17, a scholarship student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, Lewis joined with a small group of young people dedicated to non-violent protest. They became known as "the Sit-In Kids." Their mission: to desegregate lunch counters and movie theaters in Nashville.

The late Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Halberstam spent years documenting the story of the young people who changed history. "It was the first big story I ever covered," Halberstam said. "These young people were my heroes. I watched them from that day in February 1960, and thought they were doing something historic."

Of Lewis, he said, "There was something so unshakable to him, so strong, so fearless, so focused, that I thought, 'Oh, he's going to endure.'"

And at those sit-ins in Nashville, Lewis did endure violence and abuse.

"People would come up, they would pull us off the lunch counter stool, pour hot chocolate or coffee in our hair, down our back, put lighted cigarettes out in our hair," Lewis said.

He was also beaten, the first of many beatings and more than 40 arrests in his years in the civil rights movement. But in the end, Nashville surrendered to the sit-in kids. Lunch counters and other facilities were desegregated.

But Lewis and other young people were not ready to stop. They formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (known as SNCC).

"They had become warriors," Halberstam said. "A warrior can't say, 'Well, we've just, I mean, we've got totality of segregation, but we've just won a Woolworth's hamburger, let's go home.' I mean, there is a dynamic, and the more you do and the more you go up against the beast of racism, the more there was to do."

For Lewis, that meant joining the first Freedom Rides, trying to desegregate bus stations in the South. He was beaten and imprisoned. Other Freedom Riders were attacked by the Ku Klux Klan, their bus firebombed in Anniston, Alabama. "Even people in the black community said we should stop the Freedom Rides, [saying] it was too dangerous," Lewis recalled.

"Well, wasn't it?" asked Braver.

"It was a danger mission, and we knew that from the outset."

"You actually wrote wills out?"

"We wrote wills. But it was important for us to make a statement that the non-violent movement, the philosophy of non-violence, would not be defeated by acts of violence."

So, the protests went on, in places like Birmingham, Alabama, where police turned fire hoses and dogs on high school students.

Halberstam said the young people leading the movement followed a deliberate strategy: "We are going to have to lure the beast out, and the beast is going to have to lash back at us. And when we do that, people will see. But it is going to entail great risk. And of course, the additional factor was that this was going to be in this new America of modern communications; it would be caught on television."

And so, the civil rights movement captured the nation's attention, and in June of 1963, young John Lewis, as chair of SNCC, was invited to join other senior civil rights leaders, including Dr. King, to meet with President Kennedy and tell him there would be a march on Washington for civil rights.

The Kennedy administration did not want any part of the march on Washington. "Well, they didn't see it as a good thing," Lewis said, "and they were also looking toward the 1964 election, and they didn't want to do anything to upset the South."

The day of the march, August 28, 1963, was, he said, "unbelievable. It was unreal."

Lewis was one of the youngest leaders to speak that day:

"We're tired of being beaten by policemen. We're tired of seeing our people locked up in jails over and over again, and then you holler, 'Be patient.' How long can we be patient? We want our freedom, and we want it now."

The march, along with the Freedom Rides and the sit-ins, led to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But there were still barriers that needed breaking. Lewis and others in the movement started training college students from all over the country to go South to register voters – and, inevitably, to be arrested.

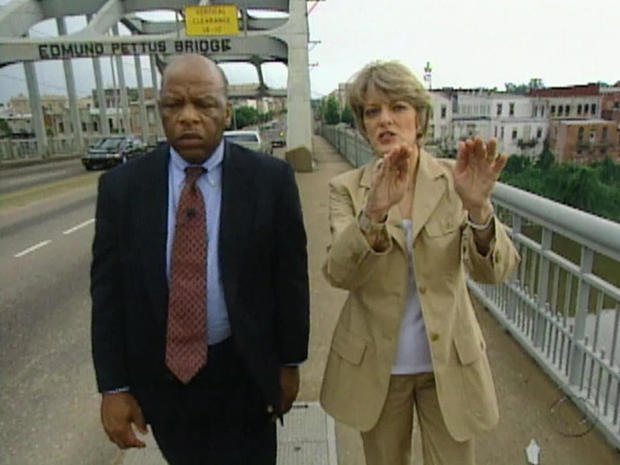

A key battleground was Selma, Alabama, where only two percent of blacks of voting age were registered to vote. But Selma authorities continued to resist change, and that led to one of the major events in civil rights history – and in John Lewis' life.

A plaque marks the spot: "On Sunday, March 7th, 1965, 600 people, led by Hosea Williams and John Lewis, began a march to Montgomery…."

"It's somewhat unbelievable that the people of Alabama and the city of Selma will see fit these many years later to place a historic plaque, a marker, here," Lewis said.

But not unbelievable at all when you think about what happened as Lewis and Williams led the protesters over Edmund Pettus Bridge on the day that became known as "Bloody Sunday."

Retracing his steps more than 30 years later, Lewis described to Braver what he saw that day: "At this point I could see lines and lines of state troopers."

The marchers were beaten with canes, clubs and whips, and sprayed with tear gas.

"I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a nightstick," Lewis said. "I really believe to this day that I saw death."

Halberstam said, "He's a simple man of great faith. That's his strength. His strength limits him from being, you know, one of these great charismatic leaders, but one day people are going to look around and say, 'Oh, my God, that's one of the great black heroes America has ever produced.'"

Braver asked Lewis, "When you look back and see those pictures of young John Lewis and his friends, do you wonder how you got the courage to do what you did then?"

"We had to do it. We had to do it," he replied. "I think there's some force, and sometimes I call it the spirit of history, that maybe, just maybe, tracked us down and said, 'This is your time, and you must do it. If you don't, who will?'"

"Every generation leaves behind a legacy. What that legacy will be is determined by the people of that generation. What legacy do you want to leave behind?" – John Lewis