From Gay Talese’s “High Notes”: “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”

Gay Talese made his name as a leader of the “New Journalism” movement, in which the boundaries of traditional reporting were broken with vivid, novelistic accounts of the reporters’ subjects.

One of the most acclaimed examples of this style was Talese’s April 1966 Esquire article, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” a deeply-revealing profile of the singer, made even more remarkable in that Sinatra would not grant Talese an interview.

Instead, the writer sought out dozens of people who knew the superstar best, making for a revealing and artfully-written portrait of a cultural icon.

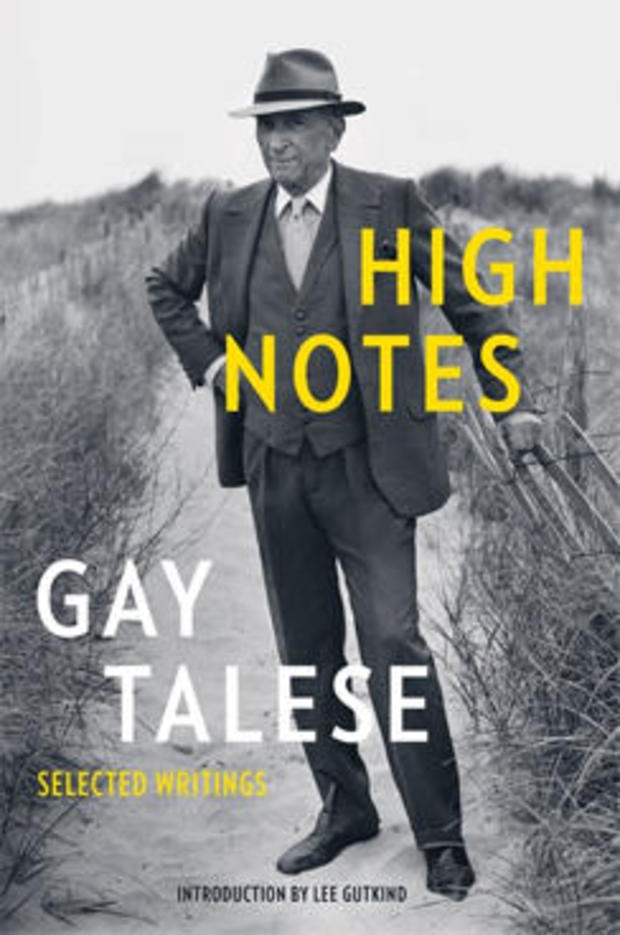

What follows is an excerpt from “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” just one of the pieces collected in a new anthology, “High Notes: Selected Writings of Gay Talese,” published by Bloomsbury Press.

- Don’t miss Rita Braver’s interview with Gay Talese on CBS’ “Sunday Morning” February 19!

Frank Sinatra, holding a glass of bourbon in one hand and a cigarette in the other, stood in a dark corner of the bar between two attractive but fading blondes who sat waiting for him to say something. But he said nothing; he had been silent during much of the evening, except now in this private club in Beverly Hills he seemed even more distant, staring out through the smoke and semidarkness into a large room beyond the bar where dozens of young couples sat huddled around small tables or twisted in the center of the floor to the clamorous clang of folk-rock music blaring from the stereo. The two blondes knew, as did Sinatra’s four male friends who stood nearby, that it was a bad idea to force conversation upon him when he was in this mood of sullen silence, a mood that had hardly been uncommon during this first week of November, a month before his fiftieth birthday.

Sinatra had been working in a film that he now disliked, could not wait to finish; he was tired of all the publicity attached to his dating the twenty-year-old Mia Farrow, who was not in sight tonight; he was angry that a CBS television documentary of his life, to be shown in two weeks, was reportedly prying into his privacy, even speculating on his possible friendship with Mafia leaders; he was worried about his starring role in an hour-long NBC show entitled Sinatra -- A Man and His Music, which would require that he sing eighteen songs with a voice that at this particular moment, just a few nights before the taping was to begin, was weak and sore and uncertain. Sinatra was ill. He was the victim of an ailment so common that most people would consider it trivial. But when it gets to Sinatra it can plunge him into a state of anguish, deep depression, panic, even rage. Frank Sinatra had a cold.

Sinatra with a cold is Picasso without paint, Ferrari without fuel -- only worse. For the common cold robs Sinatra of that uninsurable jewel, his voice, cutting into the core of his confidence, and it affects not only his own psyche but also seems to cause a kind of psychosomatic nasal drip within dozens of people who work for him, drink with him, love him, depend on him for their own welfare and stability. A Sinatra with a cold can, in a small way, send vibrations through the entertainment industry and beyond as surely as a president of the United States, suddenly sick, can shake the national economy.

For Frank Sinatra was now involved with many things involving many people -- his own film company, his record company, his private airline, his missile-parts firm, his real-estate holdings across the nation, his personal staff of seventy-five -- which are only a portion of the power he is and has come to represent. He seemed now to be also the embodiment of the fully emancipated male, perhaps the only one in America, the man who can do anything he wants, anything, can do it because he has money, the energy, and no apparent guilt. In an age when the very young seem to be taking over, protesting and picketing and demanding change, Frank Sinatra survives as a national phenomenon, one of the few prewar products to withstand the test of time. He is the champ who made the big comeback, the man who had everything, lost it, then got it back, letting nothing stand in his way, doing what few men can do: he uprooted his life, left his family, broke with everything that was familiar, learning in the process that one way to hold a woman is not to hold her. Now he has the affection of Nancy and Ava and Mia, the fine female produce of three generations, and still has the adoration of his children, the freedom of a bachelor, he does not feel old, he makes old men feel young, makes them think that if Frank Sinatra can do it, it can be done; not that they could do it, but it is still nice for other men to know, at fifty, that it can be done.

From “High Notes: Selected Writings of Gay Talese.” Copyright (c) 2016 by Gay Talese. Reproduced by permission of Bloomsbury Press. All rights reserved.

For more info:

- Gay Talese (Official site)

- “High Notes: Selected Writings of Gay Talese” by Gay Talese (Bloomsbury); Also available in eBook format