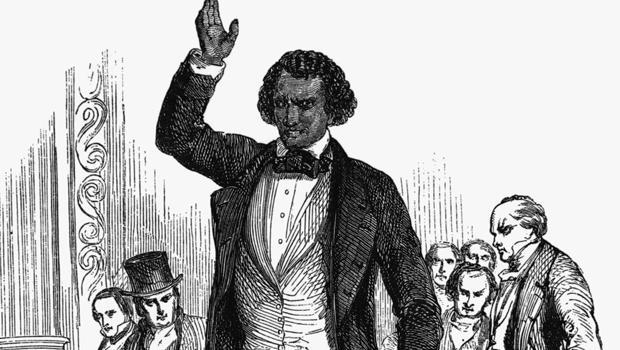

Frederick Douglass' admonition on the moral rightness of liberty for all

It is considered one of the greatest speeches in American history, delivered at a Rochester, N.Y. Independence Day event in 1852 by abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

"It is the birthday of your national independence, and of your political freedom," he said, noting, "The distance between this platform and the slave plantation from which I escaped is considerable."

Today, across Massachusetts, communities come together to read the speech aloud during the July Fourth holiday. The tradition started 11 years ago.

"What surprised me the most about people's reactions, is the sheer delight that many of our residents show when reading the address," said Keidrick Roy, a Ph.D. candidate in American studies at Harvard University, who leads the readings in Somerville, a suburb of Boston. "The conviction with which they read Douglass' words, it's inspiring. It's infectious," Roy said.

Douglass escaped slavery in 1838 and fled north, becoming a leader in the fight to abolish slavery entirely.

"This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn."

If Independence Day was a time to throw a parade, he would be the rain:

"What to the American slave is your 4th of July? I answer, a day that reveals to him – more than all other days in the year – the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham."

Roy said, "When Douglass points to the injustice and the cruelty to which they were subjected in 1852, I couldn't help but draw an immediate line to our present day. When I turn on the TV, I see people of color still being subjected to injustice and to cruelty."

The Civil War was still nearly a decade away, and slavery remained firmly in place. Douglass wanted to make it clear: this was an emergency.

New Yorker magazine contributor Kelefa Sanneh asked, "Do you think that people hearing this speech in the audience in Rochester in 1852 would've been surprised or shocked by any of it?"

"I think they might've been surprised or shocked by Douglass' boldness," Roy replied. "But they would've been awed by his eloquence."

"Fellow citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration."

"The speech begins with Douglass being very congenial and chatting with the crowd," said Roy, "getting the crowd interested in what he's about to say … and then he levies a searing critique of the United States."

"You boast of your love of liberty … while the whole political power of the nation is solemnly pledged to support and perpetuate the enslavement of three million of your countrymen."

"Though he does say that the Constitution, for instance, is still a 'glorious liberty document.' And then, toward the end he gives us a sense of hopefulness, of America achieving what it could become."

"Notwithstanding the dark picture I have to this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery."

Douglass did see the abolition of slavery in 1865. And, Roy said, the people of Massachusetts will keep sharing his words, and learning from his example.

Sanneh said, "He seems convinced not only that the country can do better, he seems convinced that the country will do better."

"Douglass is very convinced. He believes to his core that this country will do better," Roy said. "He is advocating for change, and he sees progress being made. But he doesn't let up.

"That's one of the key messages that his speech has for us today: We also can't let up in our desire to agitate to change the country."

For more info:

- Speech Text

- Amanda Kowalski Photography

- Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities, Northampton, Mass.

- Somerville Museum, Somerville, Mass.

- Frederick Douglass Neighborhood Association, Brockton, Mass.

- "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" (Podcast)

- Community Change

- Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass.

- Museum of African-American History, Boston

- Kelefa Sanneh. The New Yorker

Story produced by Mary Raffalli. Editor: Carol Ross.