Frank Stella pushes art's boundaries

The objects in Frank Stella's black paintings were grenades lobbed at the art establishment.

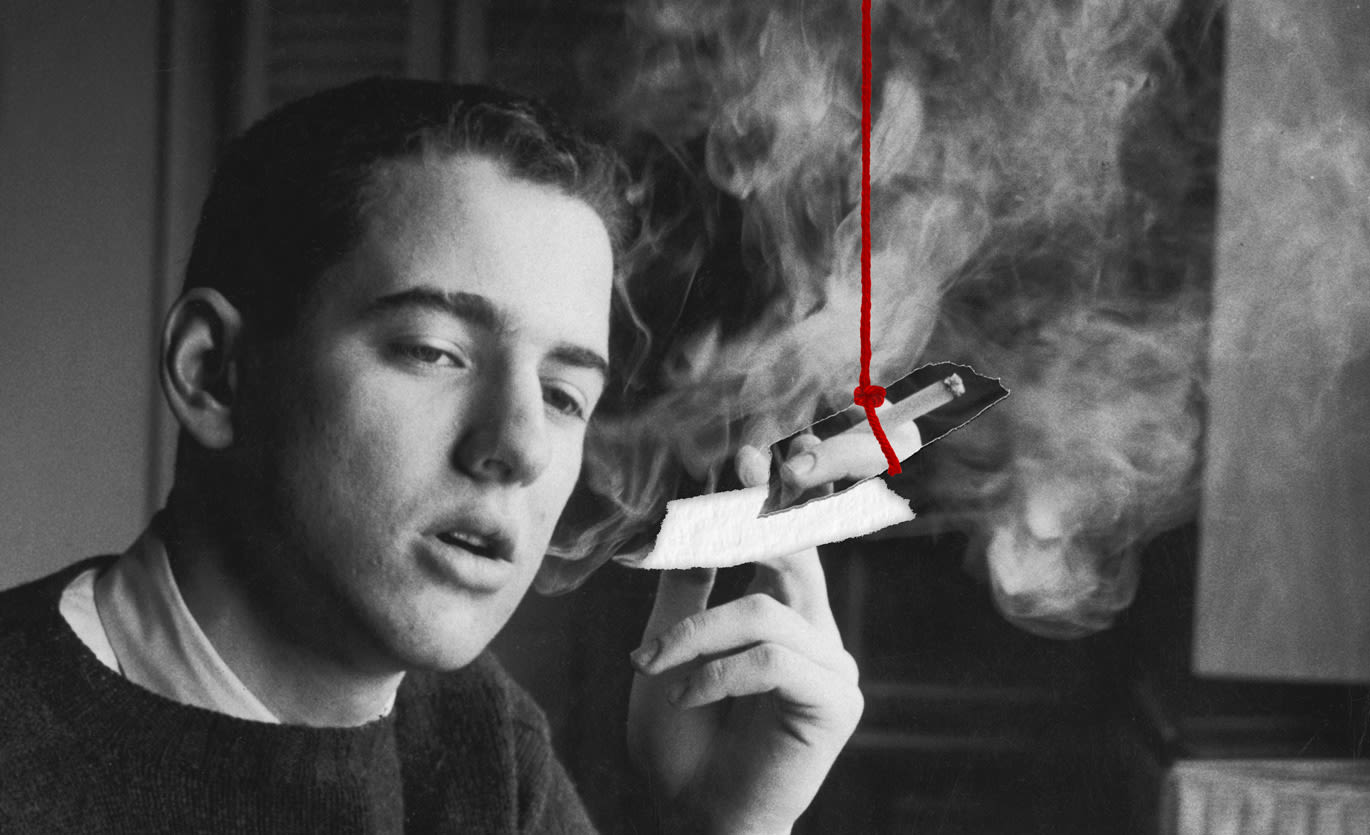

"The black paintings are a lot of things but first, perhaps, and foremost, they're structural. But basically, in the end, all paintings are painted objects," he told Sunday Morning correspondent Martha Teichner.

To watch Stella work, it may seem like a 71-year-old man playing, but he has been in the forefront of American art for nearly a half century.

It was 1959, the era of the Abstract Expressionists, lead by people like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning.

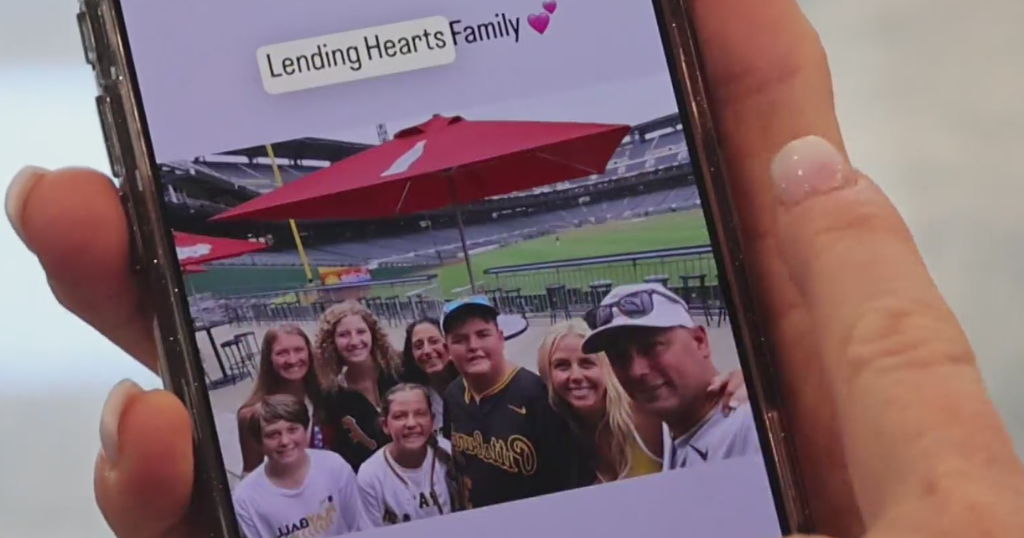

Along comes a kid from Malden, Mass., who'd majored in history (not art) at Princeton, and he was doing something new - something that came to be known as Minimalism.

At the age of 23, he became a sensation. Pretty soon, though, he started pushing the boundaries. The flat paintings gave way to layered collages which Stella calls painted reliefs.

"I like to think that the paintings are at least as alive as I am," he said.

That's about where he was in 1983, when Sunday Morning first made his acquaintance. Even then, as original Sunday Morning host Charles Kuralt noted, he was fascinated by architecture and had begun experimenting.

"You have to relate each piece to each other, and it just sort of snowballs," Stella told Kuralt. "That's the way it goes. I think the forms asked to be treated that way, that's all I can say."

Once the forms "asked" to get down from the wall, they grew wildly. By the early 1990s, he really did consider what he was doing to be architecture.

In fact, "Painting Into Architecture" was the name of a recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, tracing the evolution of his work. The only problem, he said, is that his designs are clientless, and have yet to be built - although his model of a band shell commissioned for a park in downtown Miami was almost built.

One thing that is consistent throughout his designs is the presence of a cheap beach hat that he bought long ago in Rio de Janeiro. It's there (size extra-large!) outside the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

"Look, it's America," he said. "I didn't expect it ever to get this far, and I didn't expect to get here, but I'm not unhappy at the result!"

The name of the sculpture, all 10 tons of it, is "Prinz Friedrich von Homburg" after a play and an opera. But don't bother trying to find a connection between the name and the piece. And don't try to figure out why one particular piece is part of Stella's "Moby Dick" series. Stella names his works after the fact, for his own reasons.

It's a costly profession. In 1983 he told Kuralt that for what he spends on making a piece, he could go out and buy a Porsche and paint over that.

There's been inflation since then. His pieces may cost a fortune to make but they also sell for a fortune. In 2004, Art News Magazine named Frank Stella one of the 10 most expensive living artists. Prices for pieces in a show at the Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York over the summer ranged from $135,000 to just under $1 million.

One of his paintings just sold at Sotheby's for $2.6 million, all of which is ironic since every time he tries something new, the critics brutalize him.

"Twits are twits," he said. "There's nothing you can do about it. They're not gonna change."

The critics notwithstanding, Stella is important enough to have had three - count them, three - simultaneous exhibitions, big ones, in New York just this past summer, including one on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum. You'd think he'd relax and enjoy the honor, but he is very hard on himself.

"I think it's unfortunately fair to say about me that, you know, I think I outperform my abilities," he said. "Certainly, de Kooning and Pollock were more gifted as artists than I am.

"I fit after them, but maybe closer than others."

For Stella, a man whose name means star, a career anybody else would call stellar isn't good enough. He is still at work, struggling to please himself, still consumed with the exploration of space.