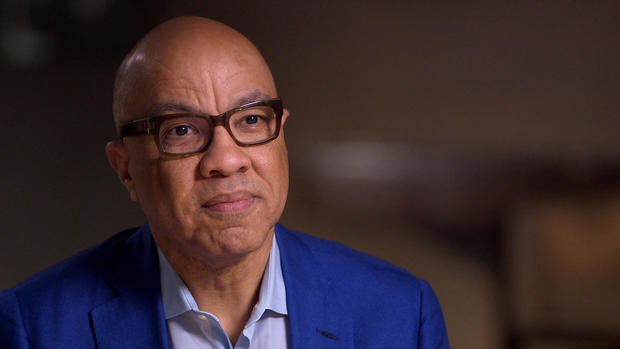

Darren Walker: How the head of the Ford Foundation wants to change philanthropy

Imagine if your job were to give away upwards of $500 million a year trying to make the world a better place. That is the enviable -- or perhaps unenviable -- task of Darren Walker, president of one of this country's largest and most prominent philanthropies, the Ford Foundation.

A gay Black man who grew up poor in a single-parent home in rural Texas, Darren Walker is probably not who Henry Ford would have chosen to give away the proceeds of the family fortune. Walker believes that in this time of stark and growing inequality -- of staggering wealth for a few, but stagnation for far too many -- philanthropy needs a major rethink. And he's using his checkbook and his charm to make the case that generosity is no longer enough.

As Ford Foundation president, Darren Walker oversees a $14 billion endowment and a landmark headquarters building in Manhattan where more than 1,500 grants are made each year to non-profit organizations in the U.S. and around the world. Its grants helped create giants like public broadcasting and Sesame Street, Human Rights Watch, and Head Start, a program Walker says made a huge difference in his own life as a poor kid in East Texas. He was in its very first class.

Lesley Stahl: Were you even aware, did you even know what the Ford Foundation was?

Darren Walker: I had no idea what the Ford Foundation was. I didn't know what policy was. But I knew that I was a lucky child. And I always felt my country was cheering me on.

Walker fears that kids living in poverty now don't feel cheered on by their country, so after he was chosen to lead the foundation in 2013 -- he'd been a vice president before that -- he did something radical.

He announced that every Ford Foundation grant moving forward would have as its mission fighting inequality in all its forms.

Darren Walker: Inequality is the greatest harm to our democracy because inequality asphyxiates hope.

His argument is that generosity is insufficient. The real goal of giving should be justice.

Lesley Stahl: What's the difference between generosity and justice?

Darren Walker: Generosity actually is more about the donor, right? So when you give money to help a homeless person, you feel good. Justice is a deeper engagement where you are actually asking, "What are the systemic reasons that put people out onto the streets?" Generosity makes the donor feel good. Justice implicates the donor.

Lesley Stahl: 'Cause you're telling the donor they're gonna have to change themselves.

Darren Walker: And that they contribute. You're the person who won't let a homeless shelter come into your neighborhood.

Lesley Stahl: Makes you uncomfortable.

Darren Walker: That's the point.

Ford Foundation video: At the Ford Foundation, we know that inequality limits the potential of all people…

As part of the foundation's new direction, Walker changed how it invests its endowment, moving a billion dollars into what are called mission-related investments -- like companies building affordable housing. He reduced funding to marquee names like Lincoln Center, while increasing grants to the Apollo Theater and Studio Museum in Harlem.

Another innovation, a new program called Build, which gives a billion dollars in grants to nonprofits and allows them to decide how to spend the money, even if it's on adding staff, or new computers.

Lesley Stahl: This is counterintuitive. Because I think most people really wanna know that the vast majority of the money they give is going to the program itself.

Darren Walker: All of the unexciting parts of a nonprofit has to be paid for-- technology and infrastructure, paying the rent. It is both arrogant and ignorant to believe that you can give money to an organization for your project, and not be concerned about the infrastructure that makes your project possible.

Walker also made changes internally. He sold the foundation's old art collection -- 400 works by White artists, all but one of them men, and bought new works by more diverse, contemporary artists like this Kehinde Wiley portrait of a woman from Brooklyn depicted as royalty, which he put right at the foundation's entrance. Walker comes from a large southern family, whose matriarch was the daughter of slaves.

He grew up in rural Ames, Texas, the segregated part of a county ironically named Liberty. COVID prevented us from traveling to Ames with Walker, but a local camera crew was able to find his first house -- now abandoned -- so he could give us a virtual tour.

Darren Walker: This house was a little shotgun shack on a dirt road. The thing about a shotgun house it usually has a door and two rooms--

Walker's mother, a nurse's aide, raised him and his younger sister on her own.

Lesley Stahl: Did you ever meet your father?

Darren Walker: I met my father once. I was about four years old. And-- my cousin brought me by and said, "Joe, this is your son, Darren. And don't you wanna say hello to him?" And he wouldn't come out of the house. I actually never saw his face because the screen door covered most of his face.

Lesley Stahl: That is so painful.

Darren Walker: I think it's painful, but I think it's also-- there's a resilience that comes from that.

Beulah Spencer: I knew the Lord had something good in store for Darren.

The resilience really came, Walker says, from his mother, Beulah Spencer --

Beulah Spencer: Education, education, education.

-- who saved up to buy the Encyclopedia Britannica for her kids, one volume at a time.

Lesley Stahl: What was Darren like as a little boy?

Beulah Spencer: Oh my god, I had to pay him to stop talkin' so much.

Lesley Stahl: (LAUGHTER)

Beulah Spencer: I'd say, "Darren--" if you'd just be quiet for 25 minutes, I'm going to give you a quarter."

He was a strong student, was elected to his mostly-White high school's student council, and attended UT-Austin on scholarship for college and law school. He moved to New York to work at a top law firm, then in banking selling bonds, and met his decades-long partner David who passed away suddenly 2 years ago. Walker put his younger sisters through college, then left banking to do community development work in Harlem, and has been in philanthropy ever since.

Beulah Spencer: I'm just proud of him. Very, very proud of him.

Especially so when that chatty little boy brought her to a state dinner at the White House, where it was she who didn't stop talking.

Beulah Spencer: I was talkin' to President Obama and Darren's standin' at the background sayin', "Mother, (LAUGH) move, move."

Darren Walker: But she broke protocol, Lesley.

Lesley Stahl: What'd she do?

Darren Walker: Because (LAUGH) she was supposed to briefly greet the president and move on. She grabbed his hand--

Lesley Stahl: (LAUGH) And held on?

Darren Walker: --with her hands (LAUGHTER) and wouldn't let go.

Lesley Stahl: But she had something to tell the president, right?

Beulah Spencer: Yes. I told him we were praying for him.

If Walker has a super-power, it's being able to get along easily with just about everyone. Pre-COVID he mingled comfortably with New York high society -- many his close friends. With a salary of almost a million dollars, he says he knows what it is to be in the bottom 1% and now the top.

Darren Walker: Let me be clear, Lesley. I am a capitalist. I believe there is no better way to organize an economy than capitalism.

But he says the system has gotten skewed, with the richest 90 people owning as much wealth as the bottom half of the country combined.

Walker on CNBC Squawkbox

Darren Walker: I want to challenge capitalism to do what it's supposed to do, and that is to provide opportunity...

So he goes on business channels calling on corporations...

Walker on CNBC Squawkbox

Darren Walker: What happened to those profit-sharing plans for workers?

...To stop putting shareholders ahead of their workers.

Darren Walker: It's unthinkable to me that it has been normalized in American culture that you can work full-time and still be poor. That is antithetical to our idea of this country. And Lesley, this isn't just an issue for African Americans and LatinX people. We have for the first time in America a generation of downwardly mobile white people.

Lesley Stahl: They're making less than their fathers did?

Darren Walker: That has huge implications for our politics.

Lesley Stahl: What's interesting is that usually when change comes, the leader is outside the tent, shouting in. You're inside. You're going to all these galas.

Darren Walker: As a person who is sometimes in the room, I think one of the things that I do in the room is to talk about uncomfortable truths.

And often people in the room are swayed. Walker pulled off a reconciliation between the Ford family and the foundation after a nearly 40-year estrangement. Henry Ford II severed relations in the 70s after clashes over bringing women onto the board, and policies he considered too liberal. Walker used that superpower of his and reached out to matriarch Martha Firestone Ford, then convinced Henry Ford III to join a far more diverse board.

This was the board's last in-person meeting before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, then George Floyd was killed, both thrusting issues of inequality to the center of the national conversation as never before, just as nonprofits including those in the arts, were fighting for their lives.

Darren Walker: Theaters went dark. Museums closed down. All of the kinds of things that we support here at the foundation, were in need, so people were panicked.

Working from home, Walker thought up a secret plan -- something no foundation had ever done -- raise a billion dollars by issuing bonds, so the foundation could double its payments to needy grantees in the arts and racial justice. The bonds were rated Triple A, and sold out in less than an hour.

Lesley Stahl: It had to be that your background suddenly came in, because you were a bond salesman.

Darren Walker: To be totally candid, it was less my knowledge of the bond market, and more the urgency I felt to do something.

Walker is calling on everyone to do something. He's turned the Ford Foundation building into a vaccination site. And in a provocative New York Times op-ed, he wrote that people with wealth and power need to share some.

Lesley Stahl: You're asking people who are invested in the system as it is, that grants them all the privilege, to give that up. I don't know if it's within human nature.

Darren Walker: I agree with you, Lesley. It's not human nature to give up privilege, particularly if you feel it's hard-earned. But at the end of the day, we elites need to understand that, while we may be benefiting from this inequality, ultimately, we are undoing the very fabric of America. We are going to have to give up some of our privilege if we want America to survive.

Produced by Shari Finkelstein. Associate producer, Braden Cleveland Bergan. Field associate producer, Justin Hayter. Broadcast associate, Wren Woodson. Edited by Joe Schanzer.