For the U.S. economy, this could be as good as it gets

Unemployment in the U.S. is at its lowest rate in more than 17 years. Paychecks are growing. In the second quarter, the nation's GDP -- the broadest gauge of economic growth -- is approaching an unheard-of 5 percent by some measures. Let the good times roll?

President Donald Trump certainly thinks so, regularly pointing to the recent surge as proof his policies are working and promising more to come. And yet many economists, stock-watchers and other financial prognosticators have a different view. They think the economic tide is cresting and is set to slow -- and soon. Here are six reasons U.S. economic performance may have already peaked.

This economy is an outlier

The current expansion is something of an anomaly. Since the Second World War, the economy has typically expanded for five to six years before going into a recession. But since the Great Recession officially ended in June 2009, the U.S. has been expanding for nine years, and this expansion is now second only to the one between 1991 and 2001.

While it may be too early to predict a recession, a growing pile of evidence indicates that growth isn't likely to speed up -- even if GDP crosses the 3 percent mark for the current quarter, or, as a few economists predict, briefly hits President Trump's promise of 4 percent.

"It's very different being an economy that's accelerating toward 4 percent and an economy that has a brief surge of 4 percent for one quarter," said Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics.

Consumers are lukewarm

Consumers fuel the majority of GDP, which makes consumer sentiment and spending an important indicator of economic health. But consumers haven't been spending all that much. It's one reason the economy grew at just a 2 percent pace in 2018's first quarter. Personal consumption expenditures were flat in the most recent quarter, with real consumer spending growing 2.3 percent year-over-year.

"That's really the weakest we've seen in over a year," said Daco. "That's a problem, especially if wage growth is not accelerating."

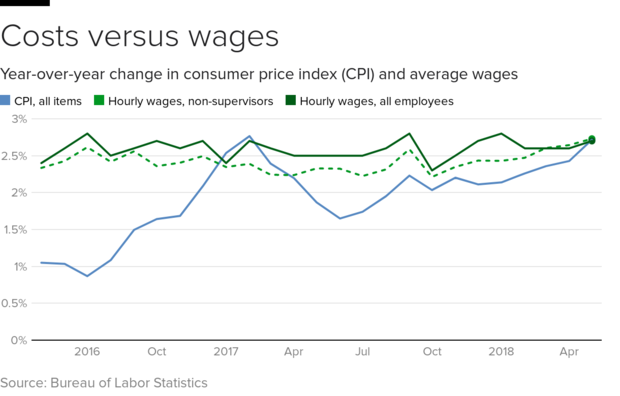

Indeed, despite a historically tight labor market, wages have been increasing only modestly, rising an average of 2.7 percent year-over-year. Meanwhile, inflation is rising at roughly the same rate. That means any pay bump the typical worker gets will likely be eaten up by increasingly expensive fuel or record-high rent.

Savings accounts are emptying out

One casualty of wages not keeping up with inflation is that Americans' savings rate has steadily declined.

While the rate has been on a gradual slide since the mid-1970s, it rebounded briefly after the financial shock of the Great Recession when Americans' rate of savings jumped. At the end of 2012, consumers were saving 11 percent of their disposable income. But since then that number has dropped to just 3 percent.

"Consumer savings have essentially been the buffer between income and spending," said Daco. "If you look at spending over the past three years, it's been hovering just under 3 percent growth. Income has been growing at just under 2 percent." And that's a risk, he said, because it means in the case of an outside shock -- like an unexpected jump in oil prices -- consumers won't have anything to fall back on.

Tariff-fueled price hikes

The biggest unknown -- and potentially the biggest shock -- comes from the tariffs being imposed by the U.S., China and the European Union.

"The way they will roll out is, first you will have objections from employers, which we've heard. Next you'll see the impact to revenue and sales. And only then, you'll see the effect in the [reduced] jobs numbers and finally layoffs," said Andrew Chamberlain, chief economist at the job site Glassdoor. "In the long run, unquestionably, the tariffs will hurt us."

They've already had an effect on some major consumer items. Americans' spending for new washing machines recorded the highest ever one-month jump in April, shortly after the Trump administration imposed tariffs and quotas on their imports, causing prices to spike. In May, manufacturers pulled back on durable goods orders, pointing to a cooling business investment climate.

At its meeting last month, the Federal Reserve's rate-setting body noted widespread concerns about the effects of tariffs. Some businesses "indicated that plans for capital spending had been scaled back or postponed as a result of uncertainty over trade policy," the Fed Open Market Committee noted in its minutes. "Contacts in the steel and aluminum industries expected higher prices as a result of the tariffs on these products but had not planned any new investments to increase capacity," it said.

The Fed's own predictions have U.S. GDP growing at a rate of 2.8 percent this year, before slowing to 2 percent. Some economists predict a sharper downturn.

"[By] the middle of next year, however, with the stimulus fading and cumulative monetary tightening beginning to bite, we expect that economic growth will slow sharply and force the Fed to cut rates in 2020," Capital Economics wrote in a note.

How's your 401(k)?

Financial markets often smell economic uncertainty before workers and consumers do, and this year has been no exception.

"In conversations with investors there seems to be some concerns that markets and the economy are due for a negative turn, mainly because the expansion has been positive for so long, now north of 9 years, that the party must be coming to an end," financial advisers for Cornerstone Wealth recently wrote. While they disagreed with that prediction, they noted that "the biggest risk to our view is the Fed, and the rate at which they continue to normalize interest rates."

In keeping with the uncertainty, stock markets have been jittery for the first half of the year, with the Dow Jones industrials average currently 8 percent below its late-January peak. While relatively few Americans are invested in the stock market, the ones who participate do so through their retirement account -- and a trade war could cut into profits of many companies in common index funds like those that track the S&P 500, Bloomberg wrote.

The dreaded yield curve

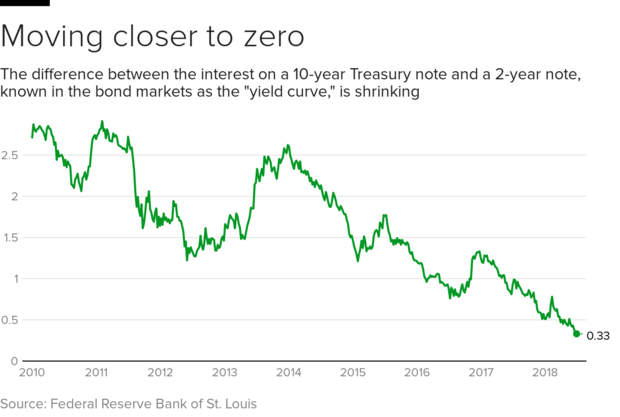

The world of bonds is also showing signs of possible worry. The yield curve -- a metric many investors watch closely -- is getting into territory that many economists say indicates a recession.

The yield curve comes from comparing different types of U.S. government debt. U.S. Treasury notes pay a higher rate of interest the longer their term. A 30-year bond will have a higher interest rate than a 10-year note, which has a higher rate than a two-year note. The interest rate on Treasuries is often viewed as a sign of the economy's future potential.

Lately, though, the Federal Reserve has been raising short-term interest rates, but long-term rates have been lagging. This shrinking gap is known as a flattening yield curve, and it has tended to precede recessions with regularity. Currently the gap is at 0.33 percentage points -- just below where it was in 2007 before the Great Recession.

An inverted yield curve, where the difference drops below zero, is a near-certain indicator of a recession. It has preceded every recession in the last 60 years, the San Francisco Fed found, with only one false flag.

One caveat: The yield curve isn't great at predicting just when a recession will hit, the San Francisco Fed noted. From the time it inverts, a recession could come in six months or two years. But it's about as close as one can get to a sure thing in the world of economic forecasting.

"What this all points to," said Daco "is, yes, we're in a strong economy, but we're past the peak."