For retailers, "shrinkage" is growing problem

As if the shift to online shopping wasn't enough of a headache for cash-strapped retailers, they're also increasingly worried about "shrinkage." That's industry jargon for merchandise that goes missing, and retailers are finding it ever-harder to combat.

A recent survey by the National Retail Federation found the shrinkage rate, which includes theft and loss of merchandise through administrative error, rose to 1.44 percent of total retail sales -- or $48.9 billion -- in 2016, compared with 1.38 percent -- or $45.2 billion -- in 2015.

Finding a solution to this problem won't be easy. Two-thirds of respondents said their loss-prevention budgets are flat or declining, and more than half expect staff sizes to be little changed.

Richard C. Hollinger, a professor emeritus at the University of Florida who has conducted the survey since 1991, argued that there may be a relationship between America's opioid crisis and retail thefts, although he hasn't seen data to prove that point. He found about 36 percent of the shrinkage results from shoplifting, and 30 percent comes from internal theft.

"My guess is that it will get worse before it gets better because retailers, particularly the brick-and-mortar retailers, are having a greater difficulty in getting shoppers into the stores," Hollinger said. "There is no way to minimize the impact of shrinkage. It's lost money, lost profitability [at a time when] retailers can't afford to lose anything."

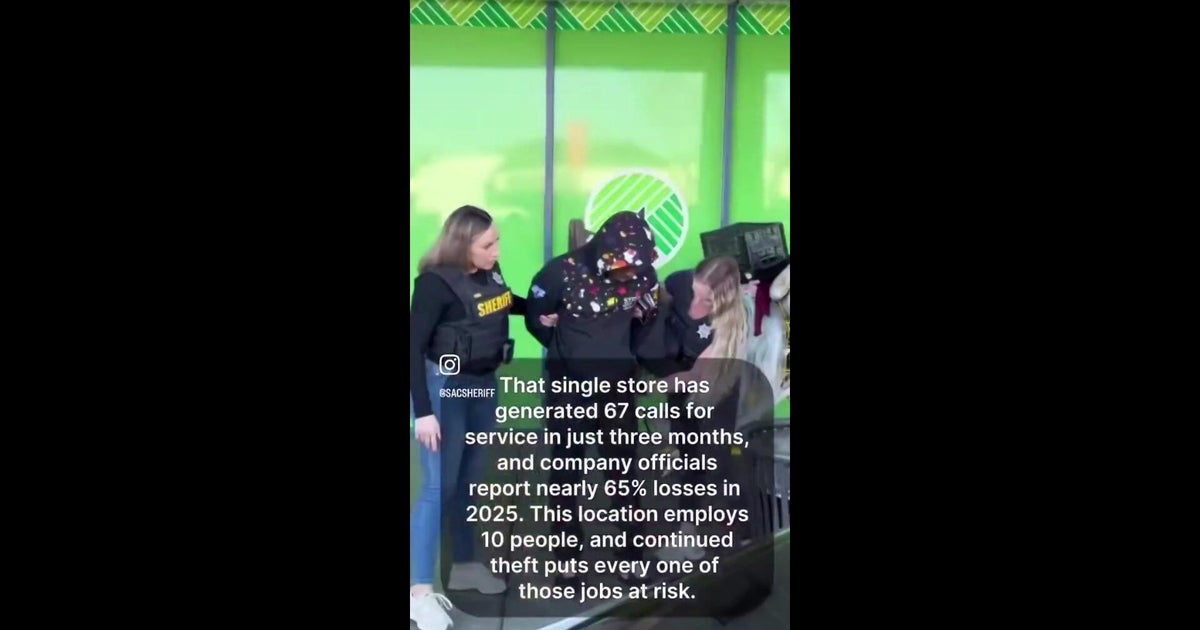

A separate survey of 23 leading chains by retail consultant Jack L. Hayes International released earlier this months found more than 56 percent of respondents reported an increase in shrinkage. The survey also found that the respondents apprehended more than 438,000 shoplifters and dishonest employees and recovered more than $120 million from them in 2016. That's an increase from the 434,000 thieves that were caught in 2015 with $118 million in stolen goods.

Hayes' data showed a 10 percent increase in thefts by dishonest employees taking advantage of the sector's declining workforce.

"There are fewer supervisors, and there are fewer employees," said Mark R. Doyle, the president of Jack L. Hayes. "Things that supervisors used to to do, like opening a locked showcase, regular associates now are doing, so it's given them more opportunities for theft. Some [retailers] are cutting back on their preemployment screening requirements, so they're not bringing in the same quality of employees as they used to."

Moreover, stores are also being targeted by gangs of shoplifters who take advantage of looser legal standards for felony theft that more than two dozen states have implemented to curb their prison populations, Doyle said. A 2016 NRF survey estimated that so-called organized retail crime costs the industry $30 billion annually.

Earlier this year, Walmart (WMT), the largest retailer, began offering programs that would allow low-risk first-time offenders the choice of participating in crime-deterrence programs rather than face criminal prosecution. As a result, the company has seen a 35 percent average reduction in law enforcement calls nationwide. Walmart declined to disclose its shrink rate.

In a statement it added: "We'll also continue working closely with local law enforcement across the country to meet our customers' and associates' expectations of a safe shopping experience."