For hedge fund baron Cohen, one Picasso too many?

(MoneyWatch) For most people, even those with bags of money, having to hand over $616 million to the government would ruin their day. For Steven Cohen, who runs hedge fund SAC Capital Advisers, it was such a relief that he went shopping -- for a Picasso. And a house. A $60 million house.

SAC, which he owns, recently agreed to two fines, one for $602 million and the other for $14 million, to settle two insider trading cases with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The settlements must be approved in court.

Not so fast, federal district judge Victor Marerro said Thursday. In refusing to immediately rubber-stamp the deal, the judge took issue with the fact that SAC was willing to pay a large fine to end the dispute, but not to admit any wrongdoing.

- SAC Capital portfolio manager arrested in NYC

- Picasso painting fetches record price

- Hedge funds disappoint -- again

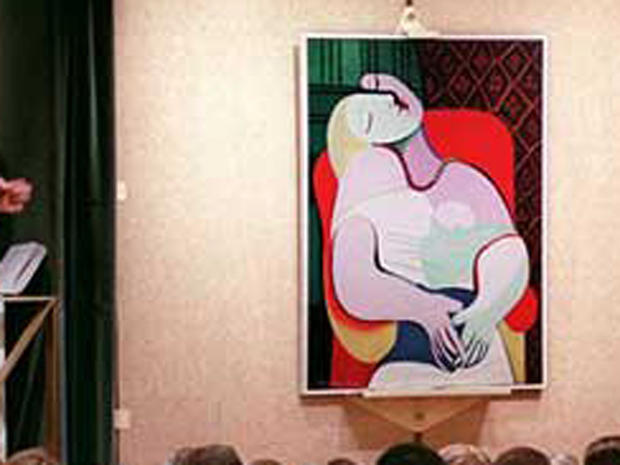

Permeating the story is Cohen's taste for the high life and his willingness to satisfy it publicly. Not long after the settlement was announced, news rolled in that Cohen had completed a deal to buy "Le Reve" by Pablo Picasso, a depiction of the artist's mistress, Marie-Therese Walter, for $155 million. He bought the painting from casino mogul Steve Wynn despite the fact that Wynn had accidentally put his elbow through it, prompting the need for restoration.

At about the same time came stories of Cohen's purchase of a new home in the Hamptons, an enclave for the rich and famous on Long Island in New York, where he already has a house. For the most part, stories have treated it as a colorful episode in the colorful life of a super-rich guy.

But the latest binge of conspicuous consumption may have ruffled the judge's feathers. Gary Aguirre, a lawyer in private practice who worked as a staff attorney at the SEC and helped bring down another hedge fund, Pequot Capital Management, thinks Cohen's actions suggest he is cocksure he won't be prosecuted. And Aguirre wonders whether Cohen just may be right.

"The flagrant, extravagant public demonstration of wealth is an in-your-face reaction to the SEC and the justice system," Aguirre said. "The guy's saying, 'I'll give you $600 million, and then I'll turn around and buy a $60 million house --because I can afford it."

The SEC didn't charge Cohen himself in the civil case, but it has accused several of his employees at his Stamford, Conn., hedge fund. In fact, the FBI today arrested the most senior SAC executive so far, portfolio manager Michael Steinberg, who was arraigned on charges that he traded the shares of two technology companies using inside information. He pleaded not guilty in a federal district court in Manhattan.

Federal settlements with large financial firms, as opposed to charging people criminally or at least taking them to trial on civil charges, have become a hot-button issue as resentment lingers over the longstanding coziness between government regulators and Wall Street, along with the lack of prosecutions stemming from the financial crisis. While agencies such as the SEC, underfunded and outgunned when going up against well-defended Wall Street financial institutions, have frequently chosen to settle, judges asked to approve the deals are getting sick of it.

Most notably, federal district judge Jed Rakoff refused in 2009 to accept a settlement between Bank of America (BAC) and the SEC in a case stemming from a suit over bonuses paid to executives after B of A's takeover of Merrill Lynch. Rakoff in 2011 also rejected a deal reached between Citigroup (C) and the agency, a decision now on appeal before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

Other judges have since refused to go along with the deals as well, but it's worth noting that those cases have all involved big banks. The ones that the government has been successfully prosecuting have charged insider trading against hedge funds such as Cohen's.

The sums paid in the settlement deals can be huge. But they have drawn criticism as little more than a cost of doing business, because the profits gained from the illicit transactions, whether insider trading in the case of Cohen's firm or the far more serious money-laundering case recently involving U.K. banking giant HSBC, are even bigger.

"What Cohen has done is to cut a deal, which allows him to pay an excise profit tax to the SEC and walk away," Aguirre said. "The judge said, 'At least we should get an admission that he's done something wrong. It just doesn't make sense to settle for that much if you haven't done anything wrong.'"

Aguirre, while acknowledging that insider trading isn't the most serious of financial crimes, argues that it undermines market stability and needs to be prosecuted.

"The only thing that stops this is for somebody to wake up in the morning in an orange jump suit," Aguirre said. "People then say, 'Hey, Charlie's in an orange jump suit! Should I really be playing this game on the other side of the line?'"