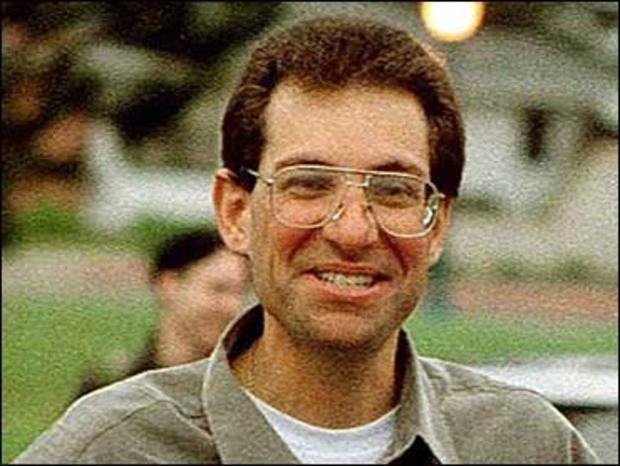

For Hacker Kevin Mitnick, Staying Legal is Job One

Kevin Mitnick was eager to participate in a

He figured it would be fun to show off his schmoozing skills, which he so easily used to trick employees at tech companies in the 1990s into handing over passwords and other sensitive information, ultimately landing him in jail.

But when he called his attorney to run it past him, the response was "Are you crazy?!"

Mitnick's lawyer, who declined to be interviewed, advised his most famous client that wire fraud statutes can be broadly interpreted such that any interstate commerce (phone calls) conducted to defraud someone, even if it is part of a contest, could be construed as a violation, according to Mitnick.

Mitnick was able to get source code and other sensitive data from companies using social engineering, a hacking technique that involves simply tricking people into offering up sensitive information, rather than technical means. He was arrested in 1995 and pleaded guilty to wire and computer fraud charges. He was released from prison in 2000 and got off supervisory release in January 2003.

Given Mitnick's

"When my lawyer says I might be committing wire fraud I get worried," Mitnick told CNET in the corridors of Defcon on Saturday. He said he was "bummed and disappointed" about not getting to compete in the event but was asked to give a talk as part of the event instead.

Attorneys for the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) advised the social-engineering contest organizers on legalities and since no confidential information was being sought the event passed muster. "We would never advise anyone to break the law," Jennifer Granick, EFF civil liberties director, said in an e-mail exchange this week.

CNET asked David Schindler, a former federal attorney who prosecuted Mitnick, for an opinion on the legalities of the social-engineering contest. A prosecutor would look at what information was being obtained from the companies, whether the purpose of the contest was to defraud or harm the company, and what was done with the information obtained, he said.

There doesn't seem to be anything "inherently illegal, but it depends on the context," said Schindler, chairman of the white collar and government investigations practice group at the law firm of Latham & Watkins. "What was the intent and what was the potential for harm?"

And what would Schindler's advice to Mitnick have been?

"It would have been a prudent piece of advice not to have your client extracting information through deception, even if you're doing it for purely educational purposes," Schindler said, adding that there's also no guarantee that someone in the audience won't misuse the information.

The situation illustrates the fine line Mitnick has to walk to avoid potential legal problems and to steer clear of anything that might make him look like he's doing something improper.

In a phone interview with CNET on Wednesday, Mitnick said he is wary of doing anything that might interfere with the consulting and public speaking business he has built up during the past decade. He's also written several books, including one on social engineering called "The Art of Deception" and has another book due out next year. Tentatively titled "Ghost in the Wires: The Adventures of the World's Most Wanted Hacker," it will be a memoir.

"Not only could I get arrested, but it would ruin my career. Everything I worked so hard to do could be gone over night. And I don't want to commit any crime," he said. While most Defcon attendees wouldn't register on Microsoft's radar, the company could conceivably try to send a message if Mitnick were to publicly shame it over percieved lax security practices.

"I have done a lot to rehabilitate my reputation," Mitnick said. "I wanted to participate to show how social engineering works, but the benefits weren't worth the risks of the legal issues and issues with companies that might decide 'hey, he's up to his old tricks.'"

Asked for his thought on Mitnick now, Schindler said, "In the end, I am always hopeful that someone I prosecuted will manage to turn his life around and do something productive with his talents."

Even though he's been on the straight and narrow path for 10 years, Mitnick has had a couple of close calls or misunderstandings related to his background.

In 2008, CNET

Mitnick declined to identify the company, except to say that it was an identity theft protection firm. However, the Web site for LifeLock shows that Mitnick is on that company's fraud advisory board.

Ironically, LifeLock doesn't need any help in damaging its reputation. Earlier this year, the company agreed

Just having the name "Kevin Mitnick" is enough to scare off some potential clients. One large antivirus firm keeps toying with the idea of hiring Mitnick as a speaker, but the executives keep backing down, he said. And a law firm wanted to hire him to be an expert witness in a computer and cell phone forensics case but withdrew the offer after learning of his past.

"That was very disappointing, but I thought it best to be up front," he said. "Usually companies hire me and they know full well who I am and that's one of the reasons they want to hire me."

Government officials don't seem to be shunning him, though. He was recently hired to give a speech at an event hosted by an intelligence agency on the East Coast, he said. After a speech at General Dynamics earlier this year, he was bombarded with requests from the audience, including FBI agents, to have their photos taken with him.

"That was surreal," he said. "I was running from these people (before) and now they are wanting autographs."

Mitnick goes to extreme measures to avoid any problems when he does penetration tests at companies that hire him to test their security defenses. For example, his contracts allow very broad discretion in conducting security assessments so that nothing he does "can be construed as illegal," he said. "I can physically go in their facility and hack any system, con any employee and they are giving me explicit written authorization."

He is careful to learn the laws of each state and country he speaks in so that when he does things like demonstrations of caller ID spoofing, a technique that obscures the real identity of a caller, he isn't breaking the law, he said.

However, Mitnick carries a business card that could be risky. It is metal and contains a set of small lock picking tools that can be dislodged. In certain states, lock-picking tools are illegal, he said.

"It's more of a novelty. I'm willing to take that chance," he said. "I'm not using them or giving them out to people who I know are doing bad."

Asked if he can ever truly repair the damage done to his reputation from his illegal hacking past, Mitnick said: "To some people I'll always be the bad guy."

This article originally appeared on CNET