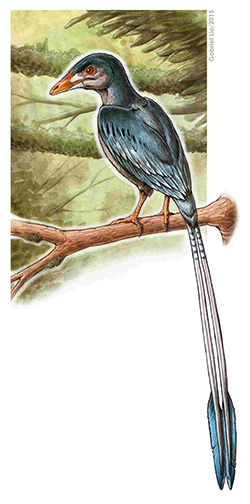

Flashy-tailed bird fossil first of its kind on ancient supercontinent

About 115 million years ago, a teenage bird with spotted, ribbonlike tail feathers flew around the trees of the supercontinent Gondwana, until it perished and fossilized in what is now northeastern Brazil, a new study finds.

At 5.5 inches (14 centimeters) from head to tail, the hummingbird-size fossil is the first of its kind to be uncovered in South America, and one of the oldest known bird fossils from Gondwana, a supercontinent that once encompassed Africa, Antarctica, Australia, India and South America, the researchers said.

What's more, it's one of the most complete and well-preserved fossils of a bird with ribbonlike tail feathers from the Early Cretaceous period, and gives researchers an unprecedented view of the intriguing plume that adorned its derriere. [See images of the remarkable bird with ribbonlike tail feathers]

The study's lead researcher, Ismar de Souza Carvalho, a professor of paleontology and geology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, said the finding was so unexpected that, at first glance, he thought, "What is this?" After a few minutes, however, he realized what it was, and that the fossil could reveal more about the history of the terrestrial ecosystems that existed at least 115 million years ago in Gondwana, he said.

Researchers found the fossil in 2011 in Brazil's Araripe Basin, a sedimentary hotspot of fossils ranging from 100 million to 120 million years old. The basin has already yielded thousands of fossilized insects, flying reptiles, turtles, fish and many different kinds of plants, all from the Cretaceous period, de Souza Carvalho told Live Science.

However, this isn't the first bird on record with ribbonlike tail feathers, he said. People have found similar specimens in northeastern China, although those weren't as well preserved, the researchers said.

Fascinating feathers

An anatomical analysis of the Brazilian fossil revealed that its flat, ribbonlike tail feathers likely didn't help the bird with balance or flight, the researchers said. Instead, these feathers may have served as ornamentation, and possibly helped the species recognize others of its kind, de Souza Carvalho said. Or, perhaps the feathers were a form of sexual display, or associated with visual communication, he said.

Either way, the tail would have stuck out. It measured about 3.1 inches (8 cm) -- longer than the bird's 2.4-inch-long (6 cm) body. Living birds no longer have the same ribbonlike feathers, researchers said, although the tropicbird comes close, with its elongated, ornamental tail feathers that blow behind it in the breeze.

"These are weird feathers that occur in extinct birds," said Richard Prum, a professor of ornithology at Yale University who was not involved with the study. "But they're on a separate line. They have nothing to do with modern feathers. It's fascinating."

The researchers also noticed that, even though the bird had developed a seemingly mature plumage, its bones weren't fully developed, and it had exceptionally large eyes for its small body. These characteristics suggest it was still a juvenile, de Souza Carvalho said. [Avian Ancestors: Images of Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

The researchers hope to find more avian specimens at Araripe Basin, to learn more about the newfound species. It belongs to the Enantiornithes, a diverse group of birds that lived during the time of the dinosaurs, but researchers have yet to give it a new genus and species.

"We are still comparing it with some birds that came from other parts of Gondwana to decide, exactly, the name that it will have," de Souza Carvalho said.

Regardless of its name, the finding verifies that Enantiornithes lived in Gondwana, not just in the northern supercontinent of Laurasia at a pivotal time of bird evolution. The Enantiornithes group is younger than Archaeopteryx, a transitional animal between nonavian dinosaurs and modern birds, and Confuciusornis, the earliest bird with a toothless beak, Prum said.

"The Enantiornithes -- this group just above Archaeopteryx and Confuciusornis in the tree -- was really global," Prum said. "We would have figured it [out] from the few fossils here and there, but this is really a great find. [It's] a whole new continent where Enantiornithes were probably flying about."

The study was published online Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.