Fla. case highlights perils of "walking while black"

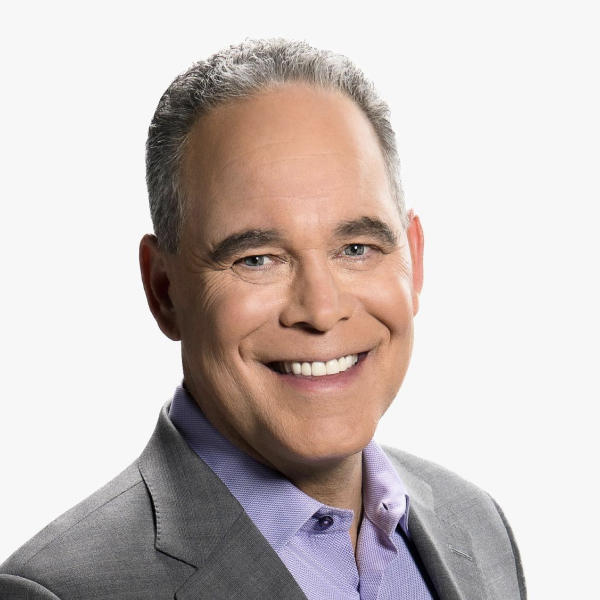

(CBS News) NEW YORK - The debate about race and crime is a reminder of a controversy in a lot of cities across the country. Back in the 1960s, the Supreme Court rule that police may stop and search anyone they find suspicious. Minorities say they are singled out. CBS News correspondent Jim Axelrod looks into this with the nation's largest police department in New York City.

Ten months ago, Nicholas Peart was walking up his block in Harlem on his way to the corner deli, when he said he was stopped and frisked by police.

"And literally they had you up against the wall?" asked Axelrod.

"Yeah. Had me up against the wall," said Peart. "I was that close to my destination "

"And you started less than 100 yards down the block here?"

"Yes. They see me come out of my building."

After an ID check, Peart, a 23-year-old college student who's never had trouble with the law, was released. Just like the other half-dozen times he said the same thing happened to him over the last seven years.

"Walking while black in my community," he said.

"That is your only offense?" Axelrod asked.

"Only offense," said Peart.

"Walking while black?"

Yes."

"What do you feel like when you walk away from having that happened?"

"I feel hopeless and violated."

New York's police commissioner Ray Kelly defends what's called the "stop-and-frisk" policy, which allows officers to detain anyone they find suspicious. The policy was put in place decades ago to combat a spike in violent crime.

NYPD statistics show 66 percent of violent crime suspects are African American. The city claims 53 percent of those stopped under "stop-and-frisk" were black. Just six percent were arrested.

"What we are trying to do is save lives and this stop-and-question tactic is certainly not the be-all and end-all," Kelly explained. "But it is one of the strategies to reduce violence."

"So what I hear you saying is, if innocent people get stopped repeatedly, that's just the price of doing business?" asked Axelord.

"Well, we certainly hope it doesn't happen. We hope that they understand that we think this is an effective strategy of reducing violence," said Kelly.

Axelrod then asked Peart: "Police officials might say, 'Look, this is how we keep the neighborhood safe.'"

"They're creating distrust in the community," said Peart. "No one wants to have anything to do with them."

"Stop-and-frisk" certainly has its fair share of critics in the New York State legislature. In fact, right now, a number of African-American and Latino lawmakers are trying to gather enough support to outlaw the practice.