Seaweed is a vital source of income and independence for women in Fiji. Climate change is washing it away.

A group of women in Fiji spend long hours trekking out to sea to gather an edible seaweed that, for years, has served as a vital part of the island nation's diet, culture and income. But now, the seaweed is becoming significantly more difficult to find, putting the livelihoods of many at risk.

Nama, also called sea grapes, is a form of seaweed known for its pearl-like structures. According to Nama Fiji, a cosmetic company that uses the sea plants, nama has high concentrations of vitamins and minerals. It's a part of Fijians' daily diet and is usually served soaked in coconut milk, Reuters reports.

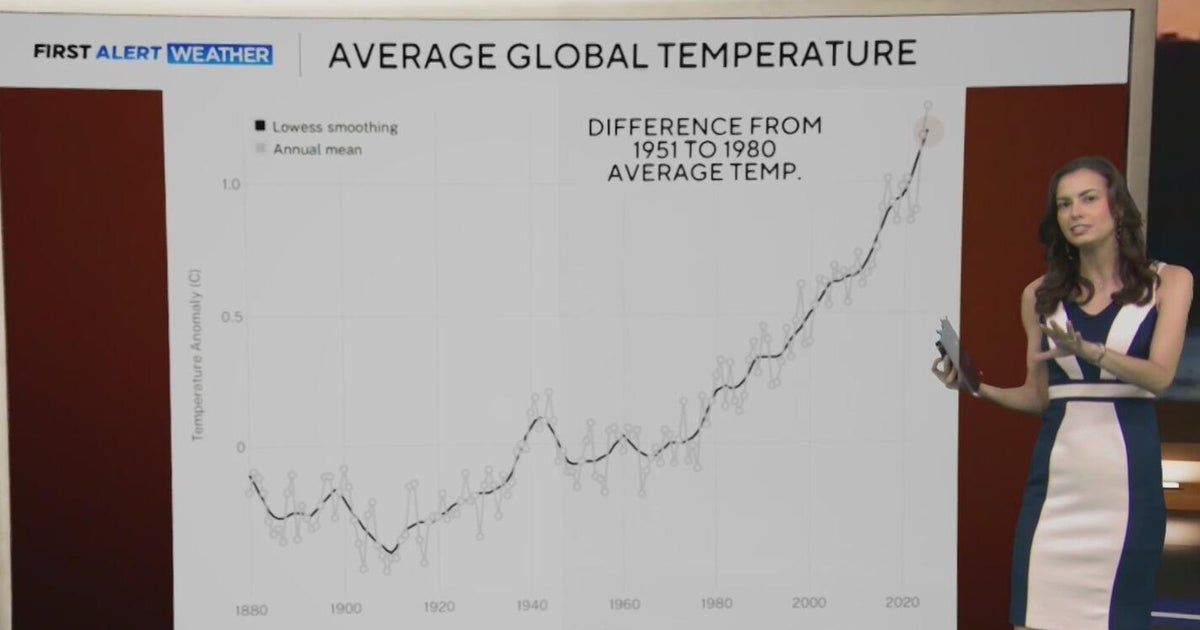

But rising global temperatures and increased storm frequency have started to impact the island's supply of nama. Fijian fisherwomen told Reuters that they now spend more time looking for the seaweed and are reaping far less of a reward.

"We are struggling," Sera Baleisasa said. "...It takes two to three hours to fill up a bag. Before it took one to one-and-a-half hour."

Karen Vusisa, 52, told Reuters she's now only able to collect about half as much nama as she once was, and spends far more time searching for it. Before, she used to be able to fill up a 44-pound potato bag with the seaweed. Now, she can only fill a 22-pound bag, a significant cut to her income.

One local woman, Miliakere Digole, told Reuters she buys nama directly from the fisherwomen before she travels several hours to sell it at a market in Fiji's capital. A 22-pound bag from the fisherwomen tends to go for about $9.13. When the women were able to gather larger bags that were about 55 pounds, they would sell for about $18.25. On average, Digole now makes a little over $40 over the course of three to four days reselling a full 55-pound bag of nama. For a 22-pound bag, she makes a little over $27.

Marine biologist Alani Tuivucilevu, who is also a coordinator for the group Women in Fisheries, called the situation sad.

"This has been their way of life. So, depletion of nama supply means, really, eroding of a way of life," she told Reuters. "...It's not only an erosion of certain species. It's also the erosion of a certain culture. Not only the Fijian culture, but the Pacific culture in general."

Tuivucilevu said the more frequent tropical cyclones mean that there's "less and less time for these nama supplies to restock."

And the storms impact more than just food and income. Tuivucilevu noted that when there's a cyclone, women are forced to stay at home, where many face domestic violence. In 2021, the Fiji Women's Crisis Centre reported more than 6,800 cases of domestic violence. Earlier this year, the center's coordinator, Shamima Ali, told The Fiji Sun that about 64% of the nation's women have experienced intimate relationship violence.

"It's a long chain of effects," Tuivucilevu told Reuters.

Baleisasa urged major countries to consider the world's island nations when they come up with their plans to tackle the climate crisis. Last year, the United Nations' sobering climate change report warned that the world's island nations are "on the edge of extinction."

To prevent significant sea level rise and even more intense cyclones, on top of other climate change impacts, the report warned that the world must reach net zero carbon dioxide emissions and reduce other greenhouse gases as soon as possible.

Tuivucilevu said that while adaptation has always been a "driving theme" for nations in the Pacific, it cannot continue.

"We cannot keep adapting," she said. "The main emitters need to recognize that the effects is not on them, that we are facing the brunt. ... Their actions, we face the consequences."