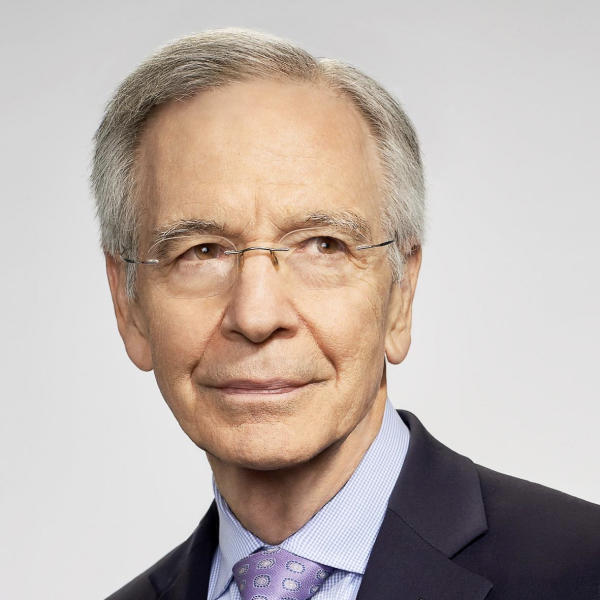

FedEx: A 50-year revolution of business

Fifty years ago Fred Smith founded the company that revolutionized business. At the sorting center at FedEx headquarters in Memphis, packages are routed around the world using computerized conveyer belts and elbow grease. Once you see it, you will never again take overnight delivery for granted.

Today FedEx employs more than 530,000 people, serving 220 countries around the world. It moves 15 million packages a day aboard a fleet of 700 airplanes, including the wide-bodied Boeing 777.

The engine of a 777 would not even fit inside the cargo hold of Smith's first plane, now on display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. That Dassault Falcon 20 aircraft was the flagship of the air express industry Smith created to meet the needs of the coming Information Age.

"Your computer goes down, you have to have the part to fix it or you're out of business," said Smith. "That's the whole principle of FedEx."

Smith saw the future when he was still an undergraduate at Yale, moonlighting as a charter pilot flying computer parts. "What I was looking at was the first stages of automation of our society, moving to a computer-based society," he said. "It was just the recognition society was automating."

Martin asked, "Did it feel like an a-ha moment to you at the time?"

"I suppose that would be a good way to describe it."

But first, there was Vietnam – two combat tours, a silver star, bronze star, and two purple hearts. Smith rose to the rank of captain in the Marines. A photograph in his office shows him with his platoon leaders. Two of them didn't come back.

Smith came home a changed man: "The Vietnam experience was the defining part of my life. Everything I ever accomplished in business is mostly what I learned in the Marine Corps, particularly about leading people."

"Are you still Captain Smith?" asked Martin.

"He comes out every once in a while, if necessary," he replied. "I found out only in the last three years that all my children called me behind my back 'Stalin.' I didn't know that! So, I'm sure there were a couple of disciplinary episodes there."

"We saw some of your frontline troops at the sorting center; your vast network couldn't function without them," Martin said. "How do you reward them?"

"The most important way we reward them is good pay and benefits," said Smith. "If you work for us, we'll put you through college."

"I thought those were part-time workers?"

"Well, they are, but they still get medical benefits and tuition refund."

Audrey Phifer went to work for Smith in Year One. "Fred came to this computer training school that I had begun taking," she told Martin. "He came himself and talked about his dream, and it was so vivid and so real that I said, Mmmm, went the next day, and got hired on the spot."

FedEx started delivering fifty years ago: April 17, 1973. "I think we had 189 pieces that day," Smith said.

Martin asked, "Did you deliver all of those packages overnight?"

"Oh, 100%. Yeah. It was pretty, pretty easy when there are only 189!"

In the first three years, the company lost $29 million. In the early days, Smith had to ask employees not to cash their paychecks. "Yes, I was one of them," Phifer laughed. "You know, it happened a couple of times that we had to hold our checks."

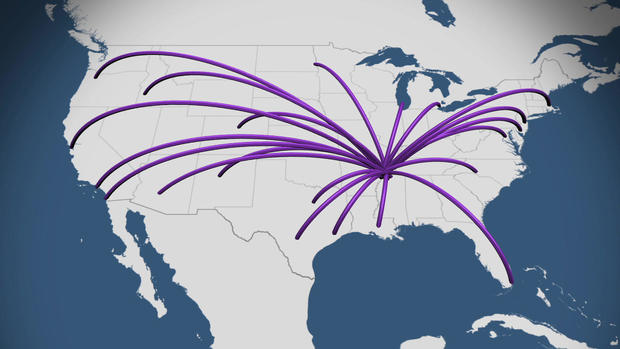

But Smith's hub-and-spoke system (planes flying into a central location, and back out to their final destination) proved that overnight delivery was possible. "It was just stunning to people that you could do that," he said. Within months there was a tenfold increase in the number of packages FedEx delivered.

Keeping track of them became the next hurdle. "The problem was that there was no technology that did that," said Smith.

The solution: a small, handheld barcode scanning device called the SuperTracker. When a package was scanned upon pickup or delivery, it transmitted the information back into FedEx's computer system. The barcodes on the outside of the package became as important as what was inside, telling conveyor belts where to direct packages toward their final destination.

"It changed logistics forever," said Smith.

On the night "Sunday Morning" visited the Memphis hub, planes were landing at one-minute intervals, each one met by a team of cargo handlers, who could unload a plane in 35-40 minutes, according to team leader Joshua Rhodes. "There are days when it can be a little stressful, but I mean, that's every job."

"You feel like you're always working against the clock?" asked Martin.

Yes, replied Rhodes, "but I mean, that is the life of FedEx."

In 2000 the FedEx life came to the big screen in the person of Tom Hanks, who played a time-obsessed manager in the movie "Cast Away." The FedEx brand name was everywhere, but the plot had public relations disaster written all over it. Smith said, "When I told our senior VP of marketing that I'd agreed to let a FedEx plane be crashed with Tom Hanks in it, he almost passed out."

It became what Smith calls a $100 million infomercial for a company that is always racing the clock.

"Those packages just don't stop moving," said Martin.

Smith replied, "You don't want them to sit there, because that's just idle cost."

Within hours of landing, the planes are loaded and ready to take off again.

In the control tower at Memphis, Al Coleman needs to get each plane airborne within 15 minutes of pushing back from the gate. "We like burning fuel in-flight, and not taxiing," he said.

Martin asked, "Is there a difference between controlling cargo planes and passenger planes?"

"No, sir," said Coleman. "The only difference is packages don't complain."

That much was true before Fred Smith. He came along and changed everything else.

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Walsh. Editor: Remington Korper.