How the Fed's interest rate hike hits consumers

For only the second time in more than a decade, the Federal Reserve has raised short-term interest rates.

The interest rate that the Fed controls affects what banks pay to borrow money from each other. That rate, in turn, affects how much interest consumers pay on everything from their mortgages and credit cards to car and small business loans.

It’s only the second time in eight years the Fed is raising the key rate, which hovered between 0.25 percent and 0.50 percent since December 2015. Prior to that, the rate had sat near zero for seven years, a historically long period of “easy money.” The central bank slashed rates in 2008 as the economy was buckling following the financial crisis, hoping to shore up growth by encouraging consumers and businesses to borrow.

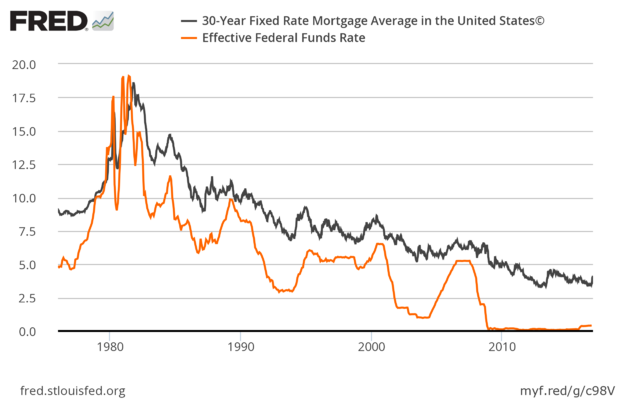

Because the interest rate set by the Fed, called the federal funds rate, affects short-term loans between banks, it tends not to have a direct effect on mortages, most of which are long-term loans. But home loan costs have closely tracked the federal funds rate for the past 40 years.

Rates have been steadily rising for two weeks, according to Freddie Mac data, as more and more lenders were expecting the Fed to hike rates. Around the U.S., interest rates for a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage average 4.16 percent, up from around 3.5 percent in November.

People with variable-rate debt, especially adjustable rate mortgages or home-equity loans, will see the biggest impact, said Greg McBride, Bankrate.com’s chief financial analyst.

“It’s a great time to insulate yourself from future rate increases by refinancing out of an adjustable-rate mortgage into a fixed rate or another adjustable mortgage that offers a fixed rate for a period of years, pay down high-interest credit card debt, or grab one of these zero-percent balance transfer offers that can give you two years to pay off that balance,” McBride told CBS MoneyWatch.

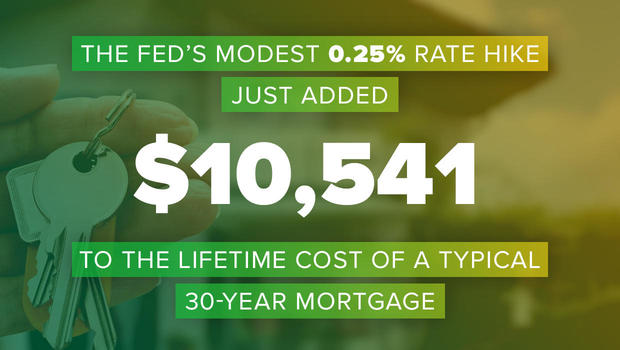

But a rise in the federal funds rate impacts fixed-rate mortgages, too. At current rates, a consumer buying a $250,000 home (priced slightly above the median) and putting down 20 percent would have a monthly mortgage payment of $970. If that interest rate goes up by a quarter of a percentage point, to 4.38 percent, that homeowner would be paying $29 more a month. Over the life of the mortgage, that small interest hike adds up to an additional $10,541.

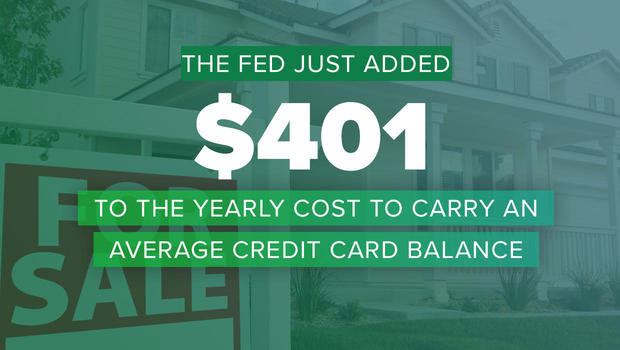

When it comes to credit-card debt, a quarter-point hike means that every $1,000 costs an additional $25 a year to carry. For the average American household, with an average indebtedness of $16,061, according to NerdWallet, that’s an extra $401 a year to carry the balance.

In the short-term, most student loan borrowers are unlikely to be affected by the Fed’s move. The rates for federally backed loans are set by Congress -- they do not depend on the Fed rate. But because government loans are linked to 10-year Treasury rates, which are affected by the federal funds rate, the cost of federal student loans will also increase over time as the Fed tightens monetary policy.

Students who hold private loans whose rates are variable will likely see their interest rates go up. Private loans make up about 9 percent of all college loans, according to figures from the College Board.

In the realm of car loans, even though the trend has been toward longer loans and more expensive cars, the Fed’s rate hike affects monthly payments only modestly. On a typical $32,000, 68-month loan, a quarter-point hike adds $4 to the monthly payment.

Savers worried about taking a hit should keep an eye on offers from online banks, community banks and credit unions, McBride suggested. But they should not expect interest rates on savings accounts and CDs to rise rapidly.

“Unfortunately for savers, the landscape is not going to change in the near term,” he said. “It’ll probably take a couple more rate hikes from the Fed before you start to see broad improvement in savings returns.”

The Fed’s move to raise borrowing costs represents an effort to head off a possible jump in inflation as the labor market continues to firm, as policy makers expect. But it also amounts a calculated bet that the economy is strong enough to withstand tightening.

It’s a big bet. For the year, the Fed forecasts the economy to grow at a rate of only 1.9 percent, down from 2.4 percent in 2015. The central bank expects gross domestic product -- the total value of goods and services -- to hover around 2 percent over the next three years -- that’s weak compared the economy’s rate of expansion in the years before the housing bust.

Despite that sluggish performance, the Federal Open Markets Committee is forecasting three rate hikes next year, up from the two it had predicted in September, and is considering raising rates more quickly than previously anticipated.

Capital Economics expects one rate hike in the first half of 2017, and three more in the second half, bringing the target range to between 1.5 percent and 1.75 percent.