Federal Reserve cuts interest rates for second time in seven weeks

- The Federal Reserve on Wednesday cut its key interest rate for the second time in less than two months, indicating the economy was hampered by trade wars.

- Chairman Jerome Powell said he would consider a series of rate cuts if the economy slowed sharply.

- Most members of the Fed's rate-setting body don't see rates dropping further this year.

The Federal Reserve further cut interest rates Wednesday as it tries to extend the U.S. economic expansion in the face of President Donald Trump's trade war with China and geopolitical risks such as the attacks on Saudi Arabia's oil facilities.

The Fed trimmed rates modestly to a range between 1.75% and 2%. It was its second rate cut this year, after the central bank cut rates July 30 for the first time in a decade.

In announcing the cut, the Fed cited lower business investments and exports, as well as persistently low inflation that suggests more economic sluggishness than the central bank wants. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell also said Wednesday that the Fed could cut rates even further if the trade war were to escalate and drag down growth.

"If the economy does turn down, a sequence of rate cuts could be appropriate," Powell told reporters Wednesday afternoon, while adding that the Fed's rate-setting body doesn't predict a downturn.

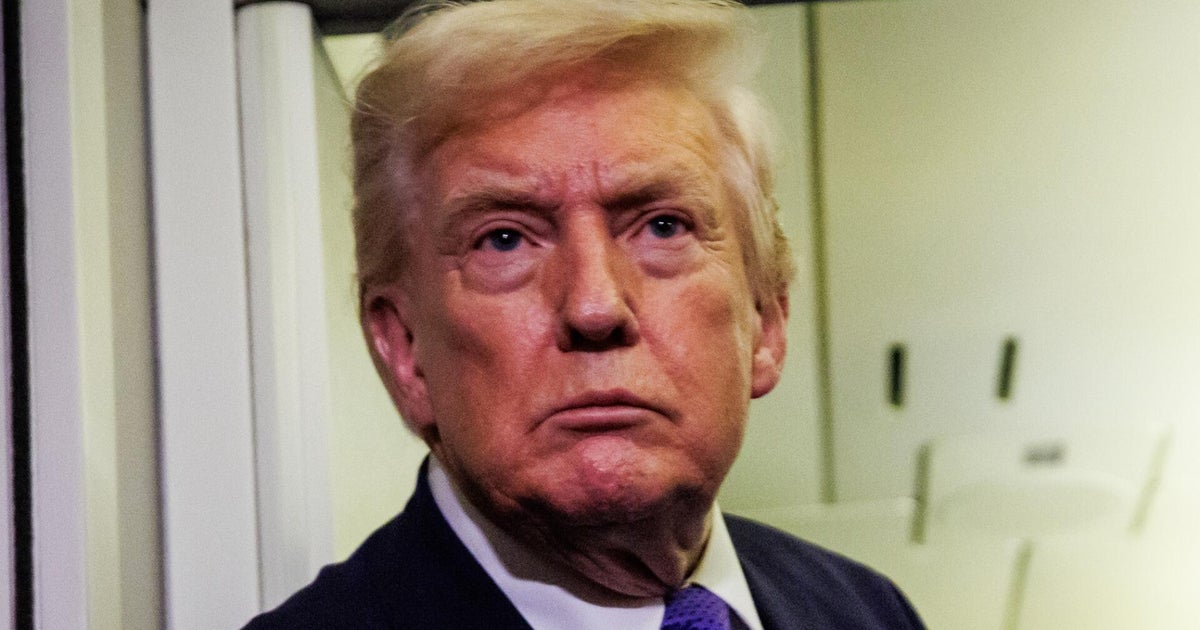

Mr. Trump, meanwhile, has kept up a stream of public attacks on the central bank's policymaking. Shortly after the Fed's announcement, the president tweeted, "Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve Fail Again. No "guts," no sense, no vision! A terrible communicator!"

He had recently called the central bank leadership team "boneheads."

Despite a still-solid job market and brisk spending by consumers, the president has insisted that the Fed slash its benchmark rate aggressively — even to below zero, as the European Central Bank has done — in part to weaken the U.S. dollar and make American exports more competitive.

Powell poured cold water on that idea Wednesday, saying that even in a recession, "I do not think we'll be using negative interest rates." But he defended the Fed's use of rate cuts as a counter to the negative effects of Mr. Trump's trade policy.

"Anything that affects the achievement of our goals is something that monetary policy could address," he said.

"The thing we can't address really is what businesses would like, which is a settled roadmap for international trade," he continued. "But we do have a very powerful tool that can support demand through sound monetary policy."

Diverging opinions

How low the Fed's rates will go remains an open question. Just seven of the 17 members on the Fed's rate-setting body predicted an additional rate cut this year, according to economic projections released Wednesday. And Wednesday's decision to cut rates was split. Two members, Esther George and Eric Rosengren, did not want to cut rates, while James Bullard wanted to cut rates even more, by half a percentage point.

"The divergence of opinions on the committee reflect the mixed data coming from the economy," observed Ben Ayers, senior economist at Nationwide. "The business sector is struggling with the trade disruptions and has slowed sharply, while the state of the consumer remains strong and is driving more spending."

The most serious threat to the expansion is widely seen as Mr. Trump's trade war. The increased import taxes he has imposed on goods from China and Europe — and the counter-tariffs other nations have applied to U.S. exports — have hurt many American companies and scuttled plans for investment and expansion.

Last week, the Trump administration and Beijing acted to de-escalate tensions before a new round of trade talks planned for October in Washington, D.C. But most analysts foresee no significant agreement emerging this fall in a conflict that is fundamentally over Beijing's aggressive drive to supplant America's technological dominance.

Overnight interest rates spike

Along with managing investor expectations, the Fed also this week has had to contend with an unusual spike in the rates charged in overnight money markets that banks and corporations depend upon for their daily cash needs.

On Monday and Tuesday nights, overnight borrowing costs, which usually stay close to the Fed's benchmark rate, surged close to 10%. To calm markets, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York stepped in, injecting more than $53 billion into that corner of the market and following up Wednesday morning with another $75 billion.

It was the first time such an action was taken since the 2008 financial crisis.

Economists believe this week's logjam was caused in part by corporations that need cash on hand to make their quarterly tax payments and rely on overnight lending markets for the funding. Powell on Wednesday called the crunch a result of technical issues, adding that "they have no implications for the economy or our stance on monetary policies."

—With reporting by the Associated Press.