FDA panel backs widespread use of innovative heart valve that's implanted without major surgery

(AP) WASHINGTON - A panel of heart experts said Wednesday that the government should expand approval of the first artificial heart valve designed to be implanted without major surgery, despite limited information about some long-term side effects.

FDA says innovative heart valve effective, but wants expert safety review

The Food and Drug Administration's panel of outside cardiologists voted 11-0 with one abstention that the benefits of broader approval for Edwards Lifesciences' Sapien valve outweigh the risks.

The valve is currently approved for patients who aren't healthy enough to undergo the more invasive open-heart surgery, which has been used to replace the aortic valve for decades.

If FDA follows the group's advice, the implant will be approved for patients who are healthier, but still face serious risks from chest-opening surgery. Many such patients are in their 80s and have complicating medical factors like diabetes.

The FDA is not required to follow the panel's advice, though it often does. A decision is expected later this year.

Edwards Lifesciences Corp. presented data from a pivotal trial showing that patients implanted with its heart valve survived about as long as those who underwent surgery. One year after the operation, 76 percent of patients implanted with the heart valve were still alive, compared with 73 percent of those who had undergone open-heart surgery.

The numbers were close enough to meet the study's goal of showing that Sapien's survival rate was at least as good as surgery. But panelists raised a number of concerns about the valve's side effects and the accuracy of the company's trial results.

Patients who got the Sapien valve had a higher rate of stroke immediately following the procedure when compared to surgery, though rates evened out over time. Additionally, more than half of patients had leaking from the aortic heart valve, a potentially dangerous condition in which blood flows backward into the heart's ventricle chamber.

Elsewhere, panelists noted that the death rate among men was more than 3 percent higher than that for women with the Sapien valve.

In each case, panelists said more follow-up data would be needed to define the scope and severity of these issues.

Irvine, Calif.-based Edwards plans to conduct two follow-up studies to evaluate long-term safety as well as differences in gender outcomes.

About 300,000 U.S. patients suffer from deterioration of the aortic heart valve, which forces the heart to work harder to pump blood, often leading to heart failure, blood clots and sudden death. More than half of patients diagnosed with the condition, called aortic stenosis, die within two years, according to the FDA.

Every year about 50,000 people in the U.S. undergo open-heart surgery to replace the valve, which involves sawing the breastbone in half, stopping the heart, cutting out the old valve and sewing a new one into place. Thousands of other patients are turned away, deemed too old or ill to survive the operation.

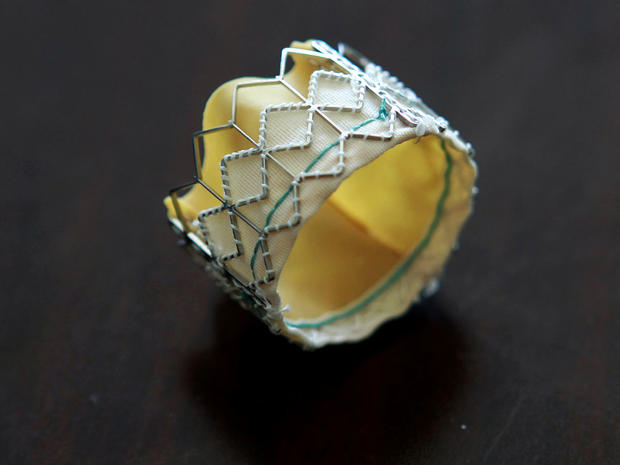

The Sapien valve is usually threaded through the femoral artery via a small incision in the leg, and then guided up to the heart via catheter. An alternate procedure inserts the valve through a small incision between the ribs. The valve is then wedged into the aortic opening by an inflatable balloon, replacing the natural heart valve. The device is made from cow tissue and polyester supported by a steel frame.

Analysts estimate as many as 70,000 to 100,000 patients per year could eventually receive the valve.