In a first, FBI to begin collecting national data on police use of force

The FBI is set to begin collecting data that will track use-of-force incidents reported by law enforcement, but experts say the collection could prove problematic and the data could provide an incomplete picture of the scale of the incidents across the country.

The National Use-of-Force Data Collection will track use-of-force incidents by police that result in death or serious bodily injury, and also incidents in which an officer fired a gun at a person, the FBI announced Wednesday. Local, state, tribal, and federal jurisdictions can begin submitting data to the FBI via a web application on Jan. 1, 2019. Once the information is collected, it will be released at least twice a year.

Law enforcement agencies across the country have come under fire for high-profile incidents of deaths and injuries by police officers. No statistics have been available to track the incidents on a national scale, though some agencies collect their own data at the state and local level.

The FBI says the data collection, a first-of-its kind effort, will allow the law enforcement community to identify areas of improvement when it comes to training and tactics. Members of a use-of-force data collection task force convened by the FBI also say they hope the data will increase transparency and in turn strengthen trust between the community and law enforcement.

"This transparency is not all the time easy -- it may involve us owning up to, 'We could have made a better decision, we could have better policies, we could have better tactics, we can train better,'" Fayetteville, N.C. Chief of Police Gina Hawkins, a member of the FBI's use-of-force data collection task force, said in a video released on the FBI's website. "Being transparent leaves us vulnerable, but being vulnerable means we want you to trust us, because we need your support, because we work for the community."

The FBI says the data won't assess whether the officers acted lawfully or within the bounds of department policy or include the final adjudication of the incident, but will aim to "offer a comprehensive view of the circumstances, subjects, and officers involved in such incidents nationwide." Data collection criteria include age, sex, race, ethnicity, height, and weight for the officer or officers and the person killed or injured. Jurisdictions will also be asked to detail information such as why officers initially approached the person, whether the person was armed or threatening an officer or someone else, and the type of force used against the person.

While the data collection effort will help departments identify mistakes, it will likely prove problematic because participation is voluntary, according to Charles Gruber, a police practices expert and federal police reforms monitor with the U.S. Department of Justice. Departments across the country are also "all over the map" when it comes to defining use-of-force, said Gruber, a former police chief.

"We're going to get something from [the data collection,] but we're not going to be able to maximize it, to use it to the extent that we could if we collected the data better and made everybody do it," Gruber said.

Some jurisdictions may not track use-of-force incidents within their own departments at all, rendering them unable to participate, while others may be reluctant to report data that will be widely publicly available, Gruber said.

The data collection program will be administered under the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting program, the same arm that collects and releases national hate crime data. That data, which is also based on voluntary reporting by law enforcement agencies, has repeatedly faced criticism of being incomplete or inaccurate. While participation is improving --about 1,000 additional law enforcement agencies contributed data in 2017 as compared to 2016 -- the Anti-Defamation League says a "serious gap" in reporting remains. At least 92 cities with populations exceeding 100,000 either did not report data to the FBI or reported zero hate crimes, according to the group.

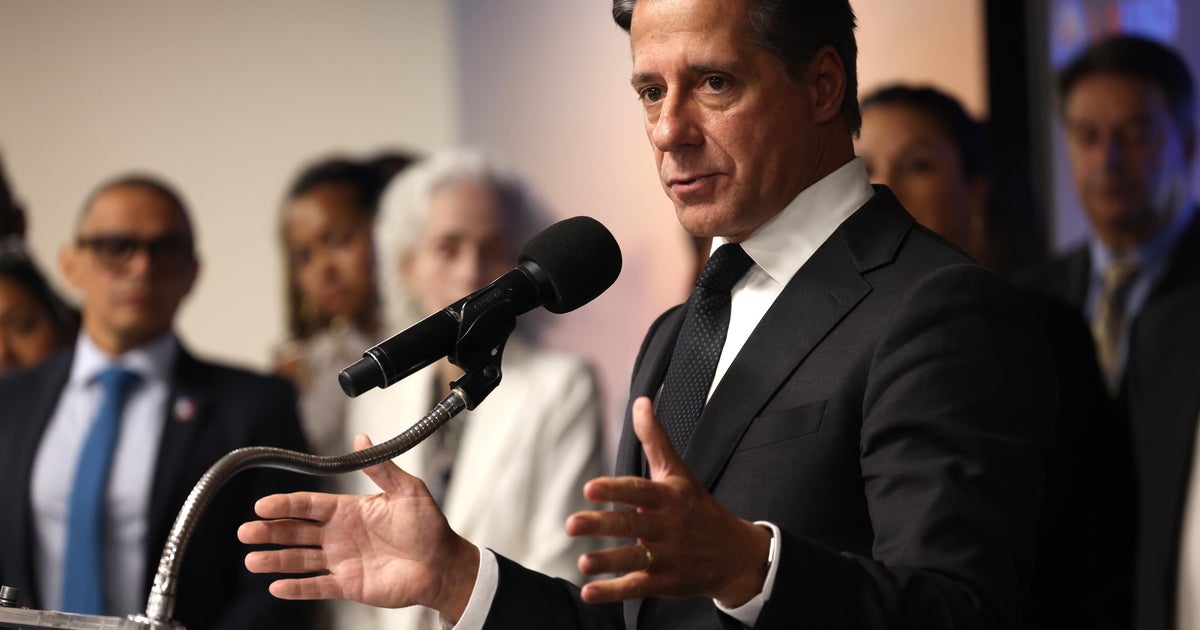

Last month, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein said the Justice Department's new hate crime initiative was "taking on the challenging task of addressing the gap in hate crime statistics" and officials were reviewing the "accuracy of those reports," the Associated Press reported.

The FBI has said is doesn't have legal authority to mandate reporting of any data to the Uniform Crime Reporting program. For the use-of-force data collection effort, it says it's working with major law enforcement agency organizations to "obtain broad support and forge commitments from these members to report this critical information."

The FBI also says they will offer data collection training for departments who participate.