Using high-tech tools to recreate and preserve ancient treasures

High-tech meets timeless craft in the Madrid workshop of Factum Arte, where they're re-imagining the art of preservation. There, they are finalizing a 21st century version of a 16th century B.C. sculpture. It's utterly realistic, yet not real.

There's no artistic license; a sarcophagus of Seti I is a reproduction, accurate to one-tenth of a millimeter.

"Factum Arte is really like one of those ideas of a Renaissance-type workshop, but in the 21st century," said Adam Lowe, the man behind Factum Arte. He's clad in the khaki colors of Indiana Jones, and has the curiosity to match.

Their mission, he acknowledges, can be difficult to explain: "Normally I say something slightly evasive like, 'We're trying to use technology to preserve cultural heritage,'" he told correspondent Seth Doane. "But what we're really doing is, we're trying to redefine the relationship between originality and authenticity."

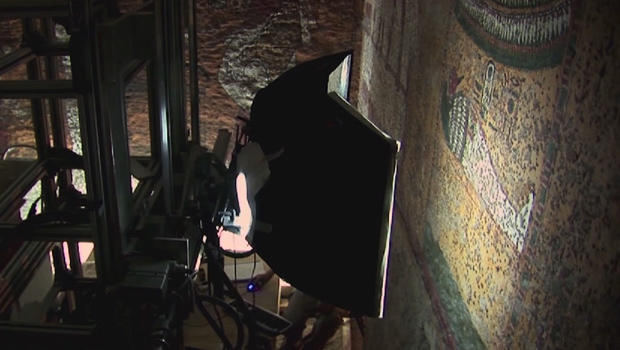

Their efforts to preserve cultural heritage involve going deep inside ancient tombs, to chapels, and famed museums, all to record masterpieces exactly as they are, using high-tech scanners.

Lowe said, "We can actually study this data up to five or six times magnification – without any data loss. So, in fact you can see the surface of the tomb better in the digital files than you can see with the naked eye on site. You can keep zooming in, so it's like a doctor using a microscope."

After the object is recorded, Factum Arte reproduces it in-house using 3-D printers and milling machines to create a base layer with all of the grooves and marks of the original. In this work, so-called "skins" are printed and laid on top.

"We're insuring they're perfectly aligned with the surface underneath," Lowe said, "and once they're in the right place we put them into a vacuum bag and suck them so that the contact adhesive forms a permanent bond."

The result? Not just the look of the original, but also the feel. "You look at this deep crack, and you can run your finger right down in the middle of that. And at that point you believe it," Lowe said, arguing that the substitute can be just as satisfying as seeing the real thing.

Doane said, "But we still want to go to the Louvre to see the original 'Mona Lisa.' It's not enough to see a print."

"I totally agree. But hanging in front of the original 'Mona Lisa' is the original 'Wedding at Cana' by Veronese, which was one of the first big projects we worked on," Lowe said.

Technicians from the Factum Foundation scanned the original "Wedding at Cana" at the Louvre in Paris, and, in 2007, the facsimile was hung in the work's original space, in Venice, filling a gaping 700-square-foot-plus hole.

Lowe said, "We know the one in the Louvre is more original. But the experience of the facsimile in Venice is perhaps more authentic."

Considering a copy more authentic is a provocative point of view: "I'd go to a dinner party in London and I'd say, 'I'm making a facsimile of the Tomb of Seti I,' everyone would go, 'How horrible.' It was one of those things that it had touched the prejudice that so many people hold."

"We recoil at this idea of forgeries, of fakes," Doane said.

"Well, a fake is something that is intentionally deceitful. There is no deceit [here]. We are very public about what we do. Everything's declared that it's a facsimile. And it's not trying to replace the original; it's trying to support the original."

Factum makes only one facsimile, while all of the scanned data belongs to the institution caring for the object. They also train local people to do the scanning, and see their work as crucial to the preservation of tombs, like that of Egyptian Pharoh Seti I.

Seti's tomb, Lowe noted, was built "to last for an eternity, but never to be visited. Cathedrals were built to be visited. Museums were built to be visited. Tombs were not."

Replicating a tomb is a technological twist on preservation, far from the methods practiced 200 years ago. After the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni discovered Seti's tomb in the early 1800s, he gouged out what he wanted to take home.

"The strange things is what was done in the name of preservation," Lowe said. "At that time, the colonial arrogance, that the only way to preserve this, was to remove it from the wall. And why remove this cartouche when you're in the most beautiful room in the tomb?"

In one of their latest large-scale works, Lowe's team recreated the so-called Hall of Beauties of Seti I's tomb, and exhibited the breathtaking room last year in Basel, Switzerland.

It will eventually find a permanent home in Egypt's Valley of the Kings, near another of Factum's monumental recreations, an exact copy of the burial chamber of Tutankhamen.

"And you can still see the original Tomb of Tutankhamen, and we're getting lots of people doing both," Lowe said. "And the response we're getting is extraordinary, that you can't tell the difference. And you know, through [attending one site], you're helping the local community by being there, you're helping preserve the tombs by being there, and by the other, you're contributing to their destruction. Which do you end up choosing?"

For a company that spends so much time studying the past, it is contemporary artists who are generally clients, and use Factum's technology to create new objects and surfaces.

It's that work that pays the bills, and allows Lowe's Factum Foundation to continue developing their modern take on preservation following the ideas set in Ancient Egypt.

"Their goal was to build a tomb, build an environment filled with human knowledge that would last for eternity," he said. "That was the goal. And it did!"

The hope here is this, too, will last, albeit in digital form, or as a facsimile – a snapshot of the original as it is today.

For more info:

Story produced by Reid Orvedahl.