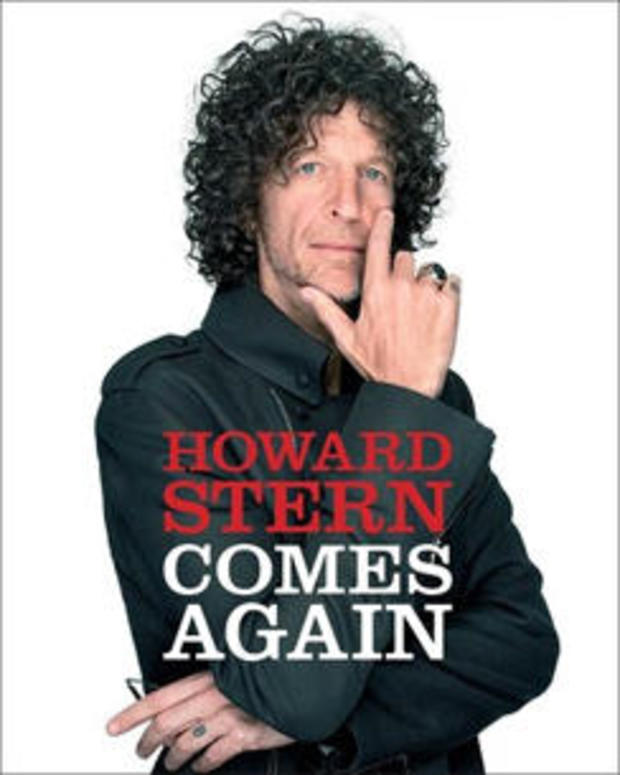

Extended transcript: Howard Stern

In this extended transcript of his interview with correspondent Tracy Smith for "Sunday Morning," broadcasting giant Howard Stern opens up about his parents and wife, psychoanalysis, apologizing for his past interviews, the freedom of being on SiriusXM satellite radio, and the art of the interview which, he says, is disappearing.

Howard Stern: My mother said to me, I said, "Oh mom, tomorrow I'm talking to 'CBS Sunday Morning.'" She goes, "Why don't you tell me you're on TV?" I go, "No, no, no." I'm trying to explain to her that it's taped in advance. (LAUGHS)

Tracy Smith: So, your first two books were best sellers, they set records.

Stern: They did.

Smith: And now you're saying, "Throw 'em away"?

Stern: Yes, yes, that's the message in the new book. First of all, I didn't expect to write a new book. You know, I was done with books, the world of books. They're torture. They take a lotta time and I actually put a lotta thought into these things. But I looked at my last two books as – it's the same way I can't really listen to my old radio shows, it's very difficult.

Smith: You don't listen to them?

Stern: No, never, I can't.

Smith: Why?

Stern: Because I feel that was me so long ago. My presentation is different. It's like, can you look at some of the old photographs of yourself? I mean, some of my hairdos, I look at those and I go, "What was I thinking?"

Smith: But it's deeper than that.

Stern: Yeah, well, it's just very difficult for me. I cringe. I was telling somebody the other day, because now that I'm promoting the book I'm going out and doing late night shows. And I don't like being interviewed, I don't like going on late night shows. For somebody who interviews, I don't like it. And because of the book, and I'm excited about it, I decided to do all of this press. So you know, in looking at my life, all of a sudden it's a big retrospective, it's very difficult and painful. And going back and looking at old shows is difficult.

I was looking at an appearance I did on Letterman, and I was cringing. It was just, my presentation was different. It's like a different guy to me. And if I've done anything in my career, I've evolved all along the way. I don't feel I ever stayed the same. So when I go back and look at that, or I look at my old books, it's not that they're horrible. It's just something different that I wouldn't do now.

Smith: What's different? What makes you cringe?

Stern: There were things in my old books that I think were hurtful to my personal life, and I don't know, sometimes the honesty … Wasn't there a song, "The honesty's too much"? ["Sometimes When We Touch" by Dan Hill.] It's just not how I would present myself now.

But that's what I loved about my career, that all along critics would say, "Well, he's gonna last a year because he does the same thing over and over again. And all he does is shock people." And whatever it is, if you go back and look at these newspaper articles and different things that I've done, they would always say, "Well, he's a flash in the pan." And now it's 40-some-odd years later, and I think what's been great is that I never stayed the same. The show has evolved. This is a completely different show than the show I did even ten years ago. And that became about because of SiriusXM and the move here, which was the smartest thing I ever did, you know, getting away from government interference. And even that's interesting, I mean, I got away from government interference, so people assumed I'd come here and it would be the raunchiest show on the planet.

Smith: Right, then you'd go totally X-rated.

Stern: Yeah. No, that's boring. I write about this in the book. There's nothing to go against there. What was great about being a wild man on terrestrial radio is that government and religious groups were against me. I loved it, I loved the action, I loved the outrageousness of it. I loved that all the hypocrites who we now see a lot of them, religious leaders who were caught in sex scandals, government people, the hypocrisy of government people who were then caught up in all kinds of outrageousness and graft and this and that, who are so concerned about what's on the radio. And then you find out behind the scenes, they're complete hypocrites. And that turned me on.

But when I got here, I had to rethink the whole thing, and I said, "What is it I wanna do?" And don't get me wrong, I still enjoy being Fart-Man and jokes on a second-grade level, there's plenty of that in the show. But this format allowed me an evolution to do what I thought were some thoughtful interviews and some fun things in a whole new way.

Smith: I wanna talk about the interviews you include in the book in a second. But first I wanna go back to this metamorphosis idea, and this idea that you don't like to look at the old work that much. You say in the book that one of your biggest regrets is Robin Williams.

Stern: Yeah, well there's a lot of regrets. A bunch of things happened in my life. I went into psychotherapy, which I'm a big proponent of. My life was in crisis. I got a divorce. I have three daughters, I was concerned about, what does life look like now? How am I a good parent on my own? I needed to take a good, hard look at myself. I didn't feel like my relationships were meaningful or deep. I thought I was too self-absorbed, I was concerned about my well-being. And so I wanted a fuller life.

Someone had suggested to me a guy named Dr. John Sarno who wrote a book on back pain. It's a fabulous book. And I became very friendly with Sarno, I'm a big disciple of his. He's no longer with us, but he said to me, "You need to go into psychotherapy. And you need a male psychotherapist." And I was like, "Well, why? I don't understand." "Trust me on this, you've got daddy issues, you know, and you need to be with a man and you need to learn what it's like to be a man and how to integrate yourself into society, if you're gonna get rid of your back pain, and also if you're gonna get healthy."

So, I began that process, so that started happening. And not only did that process become useful to me, not only did it teach me so much, and not only did I feel so much better (and I still am in psychotherapy) the main takeaway, as I described in the book, is that I started to actually for the first time in my life feel what it was like to be heard by another human being.

Smith: You didn't feel heard before then?

Stern: No, I did not. Even though I was talking to millions of people, I didn't feel heard. I'm talking about when I first sat down, the very first time I sat down with this psychiatrist, and I've been with the same guy all along, I was sitting here, and I go, "Let me tell you about my parents." 'Cause I thought that's what you do in psychotherapy, you talk about your parents. And I started to do routines, and I break into my mother, and I go, "Listen, you've got to behave yourself and you have to have rules in life." And then I'd start doing an impression of my father – and this is the stuff that kills on radio. I do this for a living. And I get a lotta laughs out of it. And he's sitting there, and I was like, What's with this guy? I'm killing right now. And he said, "There's nothing funny in any of this. And why do you feel you have to entertain me?" And that was the first experience I had with calming down and actually being heard on a human level.

And I'd never had that kind of relationship with a man before. So, this was all mind-blowing stuff to me, and I found it useful, helpful, really just phenomenal. And in writing the book, I wanted to draw the connection between being heard and then being able to sit down with someone else and hearing them. So, that's why the interviews I think became even more profound.

Smith: So in the past, you saw your interview subjects as …?

Stern: I couldn't see. I saw them as an annoyance and people who get in the way. And this is what led to what I write about Robin Williams, Gilda Radner, even Carly Simon, who probably would say she had a good time on my show, but I didn't feel satisfied. Because what would happen is when you're on terrestrial radio and you have such a hunger to be number one, as I did, and I was number one in a lot of markets, the thought of sitting down with someone famous was exciting to my audience. But what I was doing was just blurting things out, You know, "Tell me about your sex life," "What was it like when you f***** Warren Beatty," or you know, something like that. There are people who love that. But what would happen is, it doesn't lead to anything meaningful. All I was calculating as a radio guy is, "How many quarter-hours could I drag you through? How long could I keep you listening?"

The trick to having high ratings on the radio is not only having a lot of listeners, but keeping them, their interest. And this became my obsession. So if I had you on the show (and you're Robin Williams) and you stop to give me a story, I'm looking at the clock the whole time. I'm not looking at you or listening to you, I'm looking at the clock and going, "Oh God, people are tuning out. Robin's talking too long …" I was not in the right frame of mind to give someone a proper interview.

And when I look back on that, I can cringe because I love Robin Williams, I am a fan of Robin Williams. But that's the thing that opened me up in psychotherapy. I said, "Why am I not appreciating these people? These are people I adore and love, and they're walking away with the impression that I don't care about them."

So you know, there was a lot to work on there. But then moving to SiriusXM, I had a different situation. If you wanted to hear me with Robin Williams now, you could sit and listen. If you didn't, you could go over to another channel. This was liberating. I could have a meaningful conversation with Robin Williams, sit there and talk to him, and not worry. Because if you're bored or you can't handle hearing from Robin Williams, you can tune over to the coffee shop channel, or whatever it is. And so this became liberating, and great.

Smith: Going back to the Robin Williams thing, you wanted to apologize, but you didn't get the chance.

Stern: I did it with several people, I did apologize to several people. That's what I talk about cringing, that's why I can't go back and listen to those things. Writing this book was painful, because I did go all the way back to see what I was doing, and I had to go through thousands and thousands of hours of interviews, which is insane. It made me crazy, because I didn't wanna sit and listen to a lot of this stuff. It was a difficult task. So, in the case of Robin Williams and this is just awful, I wasn't calling Robin Williams to say, "Oh come back on the show." That wasn't my intent. I wanted to call him up, it all of a sudden hit me – and Robin Williams isn't the only example of this – but I wanted to call him and say, "Listen, I'm a huge fan of yours. And when you came in my studio, I was insane. I was not in the right mind to do an interview with you, and you came in so open and ready to perform, and that should have been celebrated. And I didn't celebrate you. Instead I was attacking you with questions about whether or not you were sleeping with your nanny." Which led to him clamming up and we didn't see any of his brilliance, which is so awful. "And that makes me feel bad. And I want to apologize to you for that." And I woke up one morning and I said, "I'm gonna get a hold of his number somehow, or at least an address where I can write him and tell him this in a sincere way." I'm not calling to say, "Come back on the air." I don't really sit there and solicit. I just wanted to tell him about how sorry I was. And oddly enough, I said to my wife that morning, "I'm gonna get on this." And then I believe it was either that day or the next day, whatever, but he killed himself. And I never got the chance to apologize. And I just wish I could have, you know? There are people who are still around that I have said to them, " I didn't conduct myself the proper way."

Smith: How many apologies?

Stern: Maybe I called about ten people, 15 people, and said that to. And some were very gracious. I was floored by one guy, a radio guy said to me, "I'm really glad to hear. 'Cause you know, I was, like, really sad for you, because you had so much hatred in your heart for me."

I said, "It wasn't hatred. I was in a condition where I had to have every radio listener. I had to have everything for myself." It's what I describe in the book with Rosie O'Donnell, who's become a very good friend. It wasn't that I hated Rosie, in fact I admired her, but anybody on the dial who – television or radio – who had fans, it was inconceivable to me.

I was childish, a narcissist, I wanted everyone listening to me. There was a program director when I was on terrestrial radio, they said, "You know, one in every four cars on the Long Island Expressway in New York, the largest market in the United States, is tuned into you." And all I could think about, there were three cars that weren't listening to me!

Smith: You just thought about the other three.

Stern: Yeah, I was consumed. I go, "How can that be? I'm doing revolutionary, groundbreaking radio, and there are three cars that don't care!" (LAUGHS) And that's what drove me nuts. And when you live that kinda life where you're consumed with ratings, and you know, one out of four cars? You should be celebrating, you should be dancing in the streets. One outta every four cars on the Long Island Expressway is tuned into me, you should be doing a dance. But I wasn't doing a dance; I was pretty miserable, because of those three cars that weren't listening. And so, if I would tune in and see that Rosie was having a success on daytime television, you know, no way. That can't be. How could she have success? Those people have to be tuned into me.

So this is how I conducted my life, and that's not a healthy way, I don't recommend it. And you don't need to be that way to be in radio. But that's what I needed, you know? I needed to be heard, so it's pretty wacky.

Smith: Are you happy now?

Stern: I'm a lot happier now. Yeah, I'm a lot happier now. But my wife, poor woman, I feel so loved by my wife, and I love my wife so much. But sometimes I go, "Oh, how could she put up with me?" Because I can be – I'm still pretty miserable, you know, there's still an angry guy in here somewhere. But I've learned to have a conversation with him and kinda live with him a bit, you know? You don't change in psychotherapy; you learn what's going on inside of you, and you learn how to sorta control it. It's like being the Incredible Hulk. Right now, you're talkin' to Doctor Bruce Banner, see?

Smith: But Hulk is still in there?

Stern: Hulk here, yes!

Smith: 09:11:02 So here's the thing, so therapy clearly was part of this metamorphosis, yes? But what else is it? Why do you think it is that celebrities open up to you?

Stern: I think what happens is they – and I've spent a lotta time reflecting on this – my whole career has been about honesty, painful honesty. You know, penis size, insecurities, I hate the way I look. Like right now, I'm so aware of this camera, and I have my glasses off, and I look horrible.

Smith: You don't.

Stern: Yeah, well, thank you, but I feel that way. And so I think that kind of honesty when people walk in, they feel that expectation that maybe they should open up. But I think if anything, the real trick to broadcasting and having a great interview, because the art of interviewing has kinda died. Which is a weird thing to say in the age of the podcast, 'cause everybody's interviewing everyone else. But the interview I'm talking about, going back all the way to Edward R. Murrow, is having a mass audience tune in and being excited, and staying tuned to that interview. That's a different art.

Having a podcast and just talking to your friends is maybe not the same as having millions of people hang on somebody's every word. It has to be crafted a certain way, there has to be planning involved. But I also think there's a rare quality to these interviews where people forget that they're on the radio, and that's kind of the key.

And I'm not looking necessarily for that "gotcha moment," or something like that. But I'm looking for something real. The way I'm heard in that psychiatrist's office is the way I want my guests to feel. And even like the other day, I had Seth Rogen and Charlize Theron on, and they were terrific, we were just having a very light conversation almost like a dinner conversation. But then all of a sudden something switches, everyone gets comfortable. And Charlize was able to talk about a really horrific "Me Too" moment for her. Early on in her career, she describes being about 18 years old and going for her first audition. And this producer, very prominent producer, she went over to his house, and it was at night, and he answered the door in his pajamas. Anyway, it was pretty horrible, and I really felt for her. And in the midst of that fun and frivolousness, things just became relaxed and it was okay to talk about that.

And that's why I celebrated the interviews in the book. I felt that very much with Gwyneth Paltrow, and I point to this all the time, and I'm really proud of this. Gwyneth came on, and we're sitting and having a conversation. Now, in the old days on terrestrial radio, I would have been looking at the clock on the wall like this, say, "Oh I've gotta get that quarter-hour sweep, and blah blah blah, she's going on too long." No, we're sitting and talking. Now, the audience would have expected me to say, "Gee, hey, do you **** your husband? Do you have oral sex with your husband?" Well, that would have sent Gwyneth Paltrow running out of the room. We wouldn't have known the answer, which might have been interesting! And really, what is that? Is that really how you approach a human being? Is that gonna lead to anything?

But as you see in the book, I'm sitting and talking to Gwyneth, and we're talking about marriage, and she says, "You know, sometimes I get in an argument with my husband, and it's just so much easier just to **** him." And I laughed like you did. I was like, "Oh, she volunteered that information, instead of me pushing and making it forced. And it was just a man and a woman sitting and talking about marriage in a very honest way. And that's why I included her in the book, not because she said that, but you just got this sense of her.

And then this magical thing happens afterward. People start calling me. It's like an immediate response. Oh my God, I love Gwyneth Paltrow. I never liked her when she said that about unconscious coupling, or whatever, conscious. Hated her, couldn't stand her, she's a human being to me now, I like her. I love her. Lady Gaga same thing. Guys who are like hard asses calling me up and goin', Wow, I'm gonna go to her concert. That magical thing that happens just turns me on, I love it, humanizing [celebrities].

That's what I wanted to do for Hillary Clinton. That's why I wrote that whole chapter. I was a Hillary Clinton supporter, I wanted to humanize her to those people who couldn't get past the fact a) that she was a woman, b) that there was some sort of I just hate her kind of attitude. I think she could have walked in my studio and changed enough minds – I'm not gonna be an idiot and say that it would have changed the election. But you know, I look at those numbers in a couple of key states, couple of thousand dudes in each one could have swung [the Electoral College] differently for her.

Smith: You think you could have made a difference?

Stern: I think I could have made a difference. I think there could have been a perception change. And what that change would have been is, I'm not gonna sit there and talk policy with Hillary Clinton. I know that I'm not equipped to do that, nor do I care to. I want to talk to her about being a public servant. I wanted to talk to her about her childhood, I wanted to talk to her about her decision, why she fell in love with Bill Clinton, why'd she fall in love with politics. I wanted to just sit there as two people and have a very human conversation with her. I craved it.

And I describe in the book, I loved writing this, it was like I was chasing the dream. I wanted to convince her in any way possible to sit down with me, because to take the risk, talk to a different audience, those risks weren't taken. And I think that's a warning to the next set of candidates who have to go up against Trump. And I know how Donald talks on the air, Donald knows how to communicate.

Smith: You say he's one of the best guests you had.

Stern: He is one of the best guests ever. Why? Because as a radio guest, he says whatever pops into his mind, and he understands how to play that game. Doesn't appeal to everyone, but it appeals to enough people, that style appeals to enough people, to turn them on.

Smith: So, he's a great radio guest. What do you think of him as a president?

Stern: Well, listen, he asked me to endorse him, and I couldn't.

Smith: You couldn't.

Stern: I couldn't. It's not my politics. Donald and I disagree on a lotta things. Now, I've known Donald for years. I never thought he was serious about running for president. The first time he announced he was gonna possibly run for president was part of a book promotion, which is great book promotion. "Art of the Deal" sold because he was on every talk show talking about he might be president, but he'd never run. Second book, same move. It was a brilliant move. The third time, "The Apprentice" was starting to slip in the ratings, and he had to negotiate a contract. "Let's run for president." It's a great way to get interest, and to say to NBC, "Let's negotiate." I don't think there was anything real behind [it]. He didn't think people were gonna pick up. By the way, this is my impression of knowing the guy. And Donald's always been very cordial and nice to me. He asked me to endorse him at the Republican convention and all that. And I had to say to Donald on the phone – it was uncomfortable – "I can't endorse you." And I haven't heard from him since.

Smith: You haven't heard from him since?

Stern: No, no, no, no.

Smith: You guys don't talk at all?

Stern: We don't talk at all, no.

Smith: Have you tried to get him on the show?

Stern: No, I haven't. I'm really not interested. I don't really have a lot of political guests. That's why opening up to Hillary Clinton wasn't about politics, it was about, "Hey, come off as a human being. Talk about your passion. Let me try to present you in a different way."

But Donald was at my wedding, and I know Melania, and I know Ivanka, and I know these people. And as a radio guest and as a guy, I remember I was giving the eulogy to Joan Rivers at her funeral and I remember looking in the audience. I was in the middle of telling a vagina joke. (LAUGHS) The rabbi's behind me, it's very somber, people have been going on, and on, and on, and I get up and I go, "Joan Rivers had a very dry vagina." (LAUGHS) The place goes wild. And I remember looking out and Donald Trump was sitting there and just laughing hysterically and having a good time.

I always had a good feeling about Donald. But the presidency's a different story, you know? I don't sense his passion for it. I think he'd much rather be at Mar-a-Lago. I've been to Mar-a-Lago and had dinner there, it's fantastic, it's like a dream. Why would you wanna leave? It's too great.

So I don't know what the whole thing is. But I certainly suggest that the next Democrat who does get the nomination, maybe think about dropping by the show, and not for a rousing political discussion, but a real discussion about life.

Smith: It's interesting that this is a couch. I mean, do you feel like you're a therapist in a way?

Stern: Some people have said to me, "Oh, I didn't know we were gonna do a therapy session," and this and that. But I've actually been too afraid in therapy to actually lay on a couch.

Smith: Oh, you don't lay on a couch.

Stern: I was asked if I wanted to by the therapist. 'Cause he's a psychoanalyst. It's very kind of Freudian. Like, I can't listen, I've never been able to get on a couch, lay down on a couch. I'm too insecure. I gotta know that you're looking at me. (LAUGHS) I can't do it. But there was one guest who actually, we were taking pictures afterwards, who lay down on the couch and said, "I just feel like I went through psychoanalysis," so he lay down on the couch – oh, it was Bono. And then Bono had his head in my lap. (LAUGHS) It was kinda funny.

Smith: I mean, you hear that a lot, that people feel like they went through therapy after sitting on this couch.

Stern: Yeah, yeah, and I love that. I love when someone says that. It's just the coolest thing in the world.

Smith: I see the celebrities in a lot of the videos, but I don't necessarily see where your eyes are.

Stern: Yeah, because I hate the way I look so much, I literally a lotta times on camera will hide my face behind the microphone. I'm hiding behind the microphone. This face, you know, radio was good for me. I don't think I would have had a career on television. It just wouldn't have worked. So even to this day, I'm somewhat self-conscious of my appearance. I hate doing this interview, 'cause I can't control your camera and all that (LAUGHS) kinda stuff. I just don't have a good feeling about it.

Smith: I get that. But when the interviewee is sitting here, are you maintaining eye contact the whole time?

Stern: Oh no, I'm keyed in. Oh yeah, the whole time. Some guests can't make eye contact. They look away. They look at Robin the whole time. It's really interesting. Some people can't. And then some people can totally engage.

Smith: And are there certain questions you don't ask these days?

Stern: No, I think anything's on the table. It's just, you know, I might be more sensitive about how I get there.

Smith: You don't necessarily want to hurt people's feelings? Is that fair to say?

Stern: No, I don't. I still think of my audience as sitting in the car. It's usually a man or a woman who's on their way to work. They're sitting in their car just miserable. They're miserable. There's nothing to do in their car, and if you can keep their interest where they get to work and they don't want to get out of their car, then you've succeeded. And so, if I could have a conversation with you on the air like this, and the audience is glued and really feeling great about it, I've given somebody this incredible experience.

And that's kinda how I picture it. So it's not like I'm looking to chase you outta the studio with, like, "Hey, tell me about sex with your husband last night." You know, I mean, I am curious. But seriously, if you and I got into a good discussion about marriage and maybe how hard it is or easy, or whatever it is, or your feelings about your husband, maybe we would get to a sexual discussion. We don't know. So I'm not looking to embarrass anyone. I'm not looking to suddenly throw the question that everyone's been dying to ask. I'm really after what it might be that would happen between us if you and I were sitting and having dinner together.

Smith: It's a dinner party conversation, only deeper than that.

Stern: Yeah, I think so, deeper, but yet, aware that it is a performance, too. You know, and so as deep as you can get in a conversation. I mean, deep is great. That's the shocking thing about my career now. Sitting and having conversations with people that are deep, that might be revealing. So, you know, you have to constantly change.

Smith: When I was looking at Charlize and thinking about Lena Dunham and Amy Schumer revealing to you, I mean, these deeply personal moments about sexual assault, I'm thinking, here's the guy who for years and years and years has been called a misogynist, and yet, these women have chosen to share these moments with him.

Stern: You know, even being called a misogynist was weird for me, because I didn't, again, what I was doing on the air, I thought would be entertaining, and again was kind of a performance. Like, talking to a porn star to me was interesting. That's what interested me. And it also interested me that the government and the religious groups would be in a tizzy over this thing, that they were freaking out. So as a young man, that felt like punk music to me. I was just kicking the establishment in the face, in the teeth. But, you know, it's weird to me that people would perceive me that way, but yet, I understand it. Of course they would, because that's what they were seeing.

So now when I'm talking to Amy Schumer, and she's talking about some pretty horrific stuff. Or Lena Dunham gave me one of the most open and raw interviews ever, and she opened my eyes about, I'm thinking to one conversation in the book, and I don't remember who said, it was maybe Amy Schumer. I hope I got it right. I mean, I've been workin' on this for so long, but talking about the perfect rape, about how people when they hear that someone was raped, the perfect rape is, oh, you walk down an alley, some guy jumped on you and pulled a knife and forced sex on you. But that's not how it always looks, and that's what people have to understand. She said, it was that, rape can look like I was in bed with my boyfriend, and for whatever reason, things got outta control, and I said no, and he kept goin'.

And then, when moments like that happen, and she started to talk about her own situation, I said, imagine who's listening to this. This could really change something. This could really change their world, open up somebody's mind. They're hearing this woman who is making so much sense on my show, that this could really be life-altering for some guy who maybe never got it. You know, who didn't understand, Oh, wait a second, you mean, I could be inside of you, and you could say no, and I would have to withdraw? They don't understand that. But that's an education. That's learning. So when that moment happens where, especially when I love when women come in here and talk about something like that. I think they're reaching a new audience, and it's profound.

Smith: So is part of this, that you're hoping your audience will evolve too?

Stern: Gee, I don't know if I get that heavy with it. I just hope the audience enjoys what I'm doing, and it's weird sometimes. Because Robin and I can be talking, and we're right down into the second grade humor. We're doing, like, something so weird where Sal is talking about the state of his penis and that he uses yogurt to get rid of his itchiness on his genitals. And then all of a sudden, I'm having a heavy conversation with Conan O'Brien. I love that transition. It's like a sledgehammer. Like, it's almost two different shows sometimes. And I think that's good. You just don't know what to expect, and that turns me on.

Smith: Because it's all of you. It's that silly humor--

Stern: Yes.

Smith: And then the depth.

Stern: Yes, that's why I always hated having this title "shock jock" or something. The thing that should be shocking is that there's not just one side of me being portrayed. The most boring radio to me is the political conservative radio where they spew the Republican line.

I've said this for years. Because I think it would be more interesting if once in a while they agreed with a Democrat or kind of came out with something that was completely opposite of what the party line is. That would be more interesting. I'd rather see a complete person.

I mean, don't even get me started. I have so many theories about radio and what it should be and, you know, too many to go into here. But good radio, it catches you off guard. "Oh, I didn't know he had this inside of him. I didn't know he was capable of understanding what Amy Schumer might be saying or Lena Dunham. Oh, you mean it's cool to like Lena Dunham? Oh, okay." Or, it's the unexpected. Doesn't always have to be like a pie in your face, you know?

Smith: You really think that great interviewing is a lost art?

Stern: Oh yeah, I think the art is gone. I mean, there used to be people who really knew how to attract a mass audience. So Barbara Walters I thought was fantastic at it. I mean, yes, a lot of her interviews are edited. But the idea of having great conversation that attracts a mass audience, that's the key. too. That used to mean something. And I think now what's happened is, because of technology and podcasts and everything else, and everybody has access, that there are a lotta people technically with access to this kind of equipment. And they are doing, I guess, they're having a conversation, but it isn't necessarily interesting. It's not well-crafted. There's not a whole lotta thought that goes into it. It's just sorta there.

And then what we do now, we expect everyone to just do their own editing and fast forwarding, and the actual art of the conversation is gone. And I think, if anything, the book would celebrate that these conversations are without a net. They're on the radio in real-time. If there's a screw-up, you're gonna hear it. Whatever it is, is gonna be out there, warts and all, which is exciting as hell. I would not want to do edited interviews.

Smith: No.

Stern: No, because let me do my thing. Whatever falls, falls. Whatever you might say in that interview is gonna be out there, and no one can call you, a publicist can't call you up afterwards and go, "Take that out," you know? (LAUGHS) Which, you know, would be fine. Again, I'm not looking to embarrass anyone, but there's something great about this thing going on in real-time.

And the fact that there is a collective listening to it, there's an energy that I feed off of there. If I had to do a podcast to 20 people, I think I'd still care just as much, but the idea that people weren't hearing it would really screw my head up.

And so, yes, there is a lot of interviewing going on, but I think the art and the craft of really crafting something interesting and getting something from somebody that's meaningful, and also moving the thing along and creating a rhythm and a pace, that's all kinda gone away. Right, you know, there's a handful of people who I think are really getting in there and doing it. But, you know, I think it's an important art form, because you really can learn something.

And, you know, a lot of these celebrates, famous people who have accomplished things, are harder to get things out of, because they are very savvy about what they say. So if you can crack that veneer. I mean, I didn't know anything about Charlize Theron, but oh my God, she's just so open. And I was, like, "Oh, I love her." You fall in love with that person, because they are just kinda loose, and now you kinda get a glimpse of them. So also I think part of it is, if we're gonna celebrate famous people like the book does, getting somebody in who's probably really smart and really savvy about being guarded and what they put out there, and then watching all of that melt away and then getting into something real, that's pretty cool. I love it.

Smith: What's going through your head when these interviews are going on?

Stern: Oh, it's not fun. You don't wanna be trapped in my head. (LAUGHS) It's a nightmare. I don't know how you do it, but my process is very – and that's the other thing. Maybe for other broadcasters I wanted to outline some of my process and what I do in the book. I didn't wanna get academic, but it's a very specific thing. When we book a guest, and we only book one or two guests a week, we have a big waiting list, but I also like time on the radio to groove and have days without guests. Because a lot of my show isn't about guests, it's about me! (LAUGHS) And what I'm going through. And the guest thing is something special, and you try to keep it special, and I try to bring in people that I think the audience might be interested in. But the preparation is once we announce Paul McCartney, for example, is coming in or David Letterman, or someone like that, I go into the zone.

I keep a pad everywhere, and I have this weird thing, I could always envision what something'll sound like ahead of time. I hear radio shows in my head all the time, since I was a little boy. You know, I used to be in my room when I was, I don't know, seven, eight years old, or whenever my father got me a Wollensak tape recorder and I'd make these shows, and I would imagine I was Soupy Sales. Or I was at Mad Magazine and the usual gang of idiots were all my friends. And they were just kind of coming in and out of this conversation. And I would dream of this. And I remember the first time in college I got to try it, I had this show called the King Schmaltz Bagel Hour. I got fired within, like, 20 minutes. In college radio, where you work for free, you know?

Smith: Well, there was something about making the bishop blush or something?

Stern: Yeah, right. I got fired. Oh it was crazy. It was a bit we did, too, Godzilla Goes to Harlem. And then we started takin' phone calls, and I was trying this whole idea of mine out. I had three guys who worked with me, and they were brilliant, they were much better than I was. And the program director called up, "Hi, I'm a caller to your show. Guess who I am, I'll give you three guesses, the first two don't count." And we go, "Oh, are you a Mary? Are you a sturgeon?" And he goes, "No, this is Hank, and you're all fired." I got fired on the air. I could just picture my father killing me, you know. You idiot! I could hear him in the background, You moron! So, I don't know what I was talkin' about …

Smith: Your research process.

Stern: (LAUGHS) So anyway, with guests it's very specific. I could always hear sort of, like, what Paul McCartney might sound like, and so I start to jot down all these ideas. We also have a fabulous staff, you know, I don't do this alone. And my guys do tons of research. And I have this weird thing that I describe in the book that a guy name Jon Hein that a lot of my fans would know, he's on our show, he accumulates all this research. I send him all my notes, and then about ten minutes before the guest comes in he literally just reads to me. Like, while I'm in commercial break. And if you were watching the show, you would see me just sitting there, and he starts reading to me. And he reads, and he reads, and he reads everything to me. And when I hear it, it sounds like a radio show to me, everything is memorized. I don't have to look at any notes, I don't have to. I can remember everything. It's all in my head.

Smith: And then you can just have a conversation.

Stern: Yeah, but if I had to read it, I could never retain one thing. It's weird.

Smith: But you don't enjoy these interviews?

Stern: No, I obsess over them.

Smith: Even as they're happening and you're hearing all these great things?

Stern: No. I'm picturing how it sounds over the radio. I'm kind of like, "Oh, am I getting this right?" There's a dialogue going in my head that is just, it's like a symphony going on in my head. And I really wanna get it right, I really want it to be special. And I probably want that a little too much. And so you know, I have to keep that in check. And sometimes, you know, I can blow it. I get so rigid.

I remember when Robert Plant came in. Robert Plant, I idolize him, Led Zeppelin, you know? And I remember being fixated. I wanted to learn everything I ever needed to learn about Led Zeppelin. Robert Plant wasn't interested in talking about Led Zeppelin, he didn't wanna talk about it, and he was trying to tell me nicely, and I wasn't listening, you know. I really wasn't hearing him. And as a result, I don't think I did a very good job. It's not in the book. (LAUGHS) There a little something, a blurb. But I didn't get it right. In my mind, and I go home and I'm just like, "You idiot!"

Smith: You chew on this, yes.

Stern: And I have lists of, if I ever get a second chance with a person, how I would do it. I keep meticulous lists.

Smith: Can you share any of that with me? Who do I want a second chance with?

Stern: I did a three-hour show with Billy Joel, which I include in the book, and it was a very unusual one. It was only one of the few interviews I did in front of an audience, and we had guest musicians come in and stuff. But right afterwards I said, "Oh, I should have asked him this, this, this…" and I have 50 questions if Billy walks in the door again. Same with Paul, and I've interviewed him several times. There's a whole list of people. The only one I ever thought I really got right, that was perfect, was Conan O'Brien.

Smith: Conan O'Brien, that's your best interview?

Stern: Best interview I ever did. First of all, he is brilliant. I didn't understand. I had interviewed Conan O'Brien back in the terrestrial radio days, and all I did was attack him. We had a puppet that was talking to him and attacking him. And this is what I mean about how I can't stand to go back, because Conan sat down in that chair, and I got to know him. I became a fan of Conan's in that interview. I didn't realize how brilliant he was, I didn't realize how good a talk show – if I see Conan O'Brien's gonna be a talk show guest now I have to watch. 'Cause he's that good at it, and he was open, he was honest. He talked about depression, he talked about his days at Harvard, talked about this wild kinda thing he did with Bill Cosby. These were things that he just tells in a way, he's a great storyteller. And I walked outta there and I went, "I got no issue. This is really weird. I did not screw this up in any way, it was the perfect interview."

Smith: Is it just that one?

Stern: Conan is the shine. No, there's some that I really love, and I shared those in the book. But above all others, it was Conan. Oh, I love the Jerry Seinfeld interview. And I became really good friends with Jerry after this. I go to his home regularly, got to know his wife, his kids, because Jerry invited me over after I interviewed him. 'Cause I swear to you, I felt like we were best friends after this. And he turned to me and he said, "I am never coming on your show again." I go, "Jerry, why are you doing that?" He goes, "Because that interview was so perfect. Everyone walks up to me on the street and says, 'That was the best thing we've ever heard you do.' I could never—'" I said, "Wait a second, don't punish me for doing a good interview with you." (LAUGHS) But that's Jerry's mind, because look how he walked away from "Seinfeld."

Smith: Right, right.

Stern: "I can't top 'Seinfeld.' I'm never doing another sitcom." It's fascinating.

Smith: So you chew on, , this is part of the obsessiveness, yes?

Stern: Yes, obsessive.

Smith: I wanna talk about this O.C.D.

Stern: It's horrible.

Smith: Has it gotten better?

Stern: Yes, some of the rituals have gone away.

Smith: You don't have rituals?

Stern: Well, I have it sometimes, I have to struggle with it. I know it leads to real agita in my life. Where I still think I have OCD is, I am incredibly rigid in my schedule and in my life. Like, if dinner's gonna be ten minutes later than I usually eat, I get nuts. I feel like it's the end of my world. That's why I said my poor wife, she knows. We were planning a trip this summer to go to Italy. But it's too … I can't deal with it.

Smith: Why?

Stern: Because I'm like, "Oh the time difference, and I'll be in a hotel, and I won't be comfortable, I'm not with my stuff."

Smith: So it's crippling.

Stern: I'm in a bit of a prison. Surprised this isn't a wheelchair, because it sometimes feels like that, that I can't get up and walk, you know, on my own two feet. And yet, I'm the same guy who went all around the country doing this revolutionary radio show.

Some of it doesn't add up. But radio was very, very safe for me. I always loved being in a studio by myself. That, to me, is heaven. I can sit there by myself, imagine the audience, but not have to really touch the audience, physically, or see them. And it's a discipline that I can handle. And it forces me to get up early in the morning, the scheduling of it. I have to go to bed early. If I stay out a half-hour too late, I'm not gonna be any good on the radio. It's OCD. So I'm working on that now. I still got a long way to go with this therapy, I'm still in it. One day you'll interview me. I'm gonna come back when I'm evolved.

Smith: Please. (LAUGHS) Make a promise. Yes, when you're fully evolved.

Stern: I'm gonna float in. I'm not even gonna be walking on the floor. I'm gonna be floating. (LAUGHS)

Smith: I wanna talk about the other health issue that you reveal in the book.

Stern: Yeah, that was horrible.

Smith: Yeah, so you had a big health scare and missed work.

Stern: That wasn't supposed to happen. I never miss work, that's the other thing. I am, you know, no matter what, like the post office, I gotta deliver. So it was just a very weird thing to me. And this is how childish I am, I'm under this magical conclusion that nothing bad will ever happen to me and that my health will always be good. My parents are 96 and 91, and my genetics should be good, and I shouldn't have any health problems.

So when a doctor told me, "95% chance you have kidney cancer," I was floored. This is not how I'm supposed to go out. This is not possible, I'm supposed to live a lot longer. I mean, things aren't supposed to happen to me like this.

And I didn't know how to handle it, I was in a panic. And they were like, "Don't worry, we caught it early, you were lucky," blah blah blah. I mean, I go into more detail in the book. But the weird thing about it was I couldn't admit it to the audience. I was afraid to.

Smith: Why?

Stern: Because if you do a radio show like mine, and now you see it with Twitter and social media, if you announce on the air that you're going in to remove kidney cancer, people start diagnosing, they start calling in, they start telling you about some brother of theirs who went in for the same thing and died during the operation, or some weird stuff that is all bogus science. They fill your head up, and if you have OCD, forget it. You start to believe everything they say, and I would have been a wreck.

The other thing is though, and I think it's deeper, is that I don't think I could admit to myself that this was going on. I was somehow like, maybe ashamed. Or I just couldn't deal with it, I didn't wanna admit that I was somehow getting older, and it brought out a lotta issues. I wasn't indestructible; I'm not Superman, I'm human. And it hit me like a ton of bricks.

So when the doctor called me and said – I had it all arranged that I wouldn't miss the show that morning, and then I'd have a week off to recuperate – but he said, "I think I can take you earlier." And I thought in my mind, "Oh he must be like me" (LAUGHS), this is how whacked out I am. "I wanna get to him first thing in the morning, because I'm at my best in the morning, maybe he's at his best in the morning. I'm goin' in."

So I went in, and I didn't think it would be that big a deal. Well, it became a big deal.

Smith: Well, not only was it a big deal surgically. I mean, it was serious surgery. But then on top of it, mentally like you said …

Stern: Oh my God, and then the audience was like, "Something's wrong." I'm like, how do they know that?

Smith: Did you look at death differently? Life differently?

Stern: Oh yeah, no, it rocked me. And it does cause you to evaluate what's going on in your life. And in a way, that's why the book became important to me. I was not gonna write another book, but I started to think about, "What am I leavin' behind, and what am I most proud of?" And what I'm most proud of is my relationship with my wife and my daughters. I just love these kids and what they're doing in the world. It moves me almost to tears to think about what my daughters are doing in this world. They're just beautiful people, and what it is, I might say to the audience, what is it that really moved me in my career. And it's these collection of interviews that I did, and what I might say about them.

And maybe, you know, future broadcasters might read this and say, "Oh that's how he did it, or that was his process." Or maybe there's some wisdom there, like it's weird when you read the interviews. Like, sometimes a person's voice gets in the way of the message. And I found, for example, Mike Tyson, I never understood drug addiction. It's something that's not in my world in terms of my own personal experience, I've never been addicted to drugs. And when he starts to compare it, he said, "Think of it like food. What if you hadn't eaten in two days, what might you do? That's drug addiction, that's how bad you need drugs." Now, no one had ever explained it to me the way Mike Tyson did. And then I went, "Oh I get it." Like, I'm learning from him.

I learn from every person in that book. And mostly about their climb, the drive for success. Stephen Colbert's interview rocked me, when he's talking about the death of his father, some of some of his siblings [who] died in a plane crash. Talked about religion, talked about – I mean, I became connected to him, you know? It's a beautiful thing. And interviewing became a very beautiful thing to me. And when Simon & Schuster said to me, "Oh we would love to put out a collection of your interviews," at first I was like, "Oh no, people have heard these interviews." But they proved it to me, they brought in a book and said, "Look." They put a couple of interviews and some transcripts, and I started to read through 'em, I go, "Oh you know, maybe this could be interesting to people," and that's how the whole book evolved.

Smith: Why don't you talk about your family as much on the show?

Stern: Yeah, you know, that's something I learned through therapy, like, nothing was sacred. I'm come in on the air, and it was a scorched-earth policy. But you can't have relationships if everything is available to the audience, and if everybody's a subject of your humor. And so now I know that, like, the kids, I don't wanna share all that much about my kids with the audience. You have to hold some relationships sacred. If you're gonna be in a good marriage, I can't sit there and give you every detail of what it is my wife and I might be doin' in the bedroom. I just can't share that with you. It upsets her. I didn't know this. My attitude was, when I was growing up my parents joked about everything. Not saying there was real conversation, everything was a joke. There was no real conversation. It was, as my mother would say, "Shtick." She goes, "You get your shtick from your grandfather, you get this, you get that." So to me, I wasn't out to hurt anyone, but conversation really was just funny, and you should laugh at everything.

And so I didn't draw a line. And that's not to say I don't share a lot with my audience, I do. I mean, I'm brutally honest and every neurosis and everything is discussed. In my opinion, that's where good humor comes from. That's where a funny show comes from. People wanna hear that type of honesty. I have a real intimacy with the audience. But I can still do a show and not necessarily share with you everything my wife and I are doing in the bedroom. Or maybe every little conversation we had. You know, I can now control that. But having said that, the example of my mother in the book, I saved her for the end, is one of the wildest conversations I ever had on the air.

Now, I knew my mother could handle it, because that's how we can talk. And as I say in the book, "You might be jealous of this conversation. Gee, I wish I could talk to my mother like this." But it's not a real conversation. It's me talking and it was my birthday, my mother calls in and I go, "How was I conceived? What position were you in?" (LAUGHS) What do you mean, you don't talk to your mother about this?

Smith: No, I'm just saying that this is "Sunday Morning," so that's as far as we can go there.

Stern: Oh grow up. (LAUGHS) Come on, let's talk about it.

Smith: But this is interesting because the chapter about your mom and your parents, you say one of the reasons that you did this book was so that your parents could see it while they were still here to see it.

Stern: Yeah, they still haven't seen it yet, so I better get on that! They're pretty old, My mother goes, "Where is this book already?" I go, "Mom, the book is coming out May 14th. I don't have it in my hands yet." "When am I gonna see this book? When am I gonna see the book?" I go, "I don't have one for you yet." "And when is your Aunt Mildred gonna get a book? I promised her you'd send one." And it's like, "I'm tryin' to describe to you that it's coming. Howard Stern is coming."

Smith: Yeah, by the way, the title, yes, you're so evolved.

Stern: Well, that says it all. (LAUGHS) As proud as I am of this book, and as much as I talk about an evolution, the book title still -- so if it does go to number one, and my fingers are crossed, "Howard Stern Comes Again" is number one would really please me. (LAUGHS)

Smith: 'Cause there's still that side of Howard.

Stern: Yeah, I still liked "Howard Stern's Private Parts," you know? The sense of humor is still rather childish. There's still part of me that lives for Mad Magazine, those guys were geniuses.

Smith: Going back to your family, do you think that this book will be a way to have deeper conversations with mom and dad?

Stern: I don't know. Look, my mother and I talk on the phone all the time. I go to see my mother all the time. And my father's quite old now, it's hard for him to hear, but we talk. You know, there's a relationship there that I think is kind of cemented. But actually, through therapy I've been able to go to my mother and ask her certain things, and I mean, you can get deep. My parents had really tough lives, they really did, and I think there's only so much they can handle in terms of intimacy and that kind of real conversation.

Smith: You've talked about the daddy issues.

Stern: Yeah, but so many guys have daddy issues and they don't get in touch with them. My father was always there, my father is a really honest, funny guy. But I grew up in a neighborhood that was very tough. It was a rough neighborhood. And if my father had been the kind of guy who would've come to me and said, "How are you coping with all of this? All your friends have moved away, all these white people moved away. We live in an all-black neighborhood. What's that like for you? Are you able to have friendships? What's it like when you knock on the door in the middle of the night, and your friends move out of town?" Some heavy stuff going on there. But my parents didn't know how to check in like that. They didn't know how to ask me how things were going. And I wanted to be a hero. I was very stoic. I never wanted to complain to them. I didn't want to add to their burden.

Smith: So, you didn't?

Stern: I never thought of myself. But I also shut down emotionally. I never, ever thought about myself. So, everything was kind of bottled up inside of me. And I think when I first started to really get successful on the radio, I roared like a lion.

Smith: Because all of that was coming out?

Stern: All of it came out. Yeah, yeah, had to, had to come out somewhere. Probably, if it hadn't, I probably would've gone completely psycho. (LAUGHS) It just was a good outlet for me.

Smith: Do you get a sense from mom and dad that they're proud now?

Stern: Oh, yeah.

Smith: Have they said, "We're proud of you, Howard."

Stern: Yes. I badgered my father until I said, "Dad, tell me you love me. Tell me you love me."

Smith: You did, really?

Stern: Yeah, yeah, I did that years ago on the radio, and he called up one day, "Harold, I love you." You know, like, pulling teeth, but yeah. You know, it feels like a lot of hoops you have to jump through to get that. But I think my parents were always proud of me, and they were quite tickled by my accomplishments, and always appreciated the radio show. They have a great sense of humor.

Smith: So, this book is more about you being proud of you?

Stern: This book I wrote for me. At the end of the day, you know, I get caught up in, gee, I hope everyone likes it. I had this fantasy that not only my fans will read this book, but the fantasy – and part of the reason why I sat down with you is that every publicist said to me, "Oh, 'CBS Sunday Morning' sells a lot of books." And who I was interested in reaching was maybe the person who didn't follow me to satellite radio, who used to kind of hear me every day. Or maybe someone who was turned off to me. One of the three people in their cars that weren't listening who said, "Oh, I would never read a book by Howard Stern." I wanted them to read this book and see what we're doing now, and see if it might interest them.

Smith: So, that brings up a good point. To those people out there who hear the name Howard Stern, and say, "Oh, he's vulgar, oh, he's that shock jock – "

Stern: Well, listen, I'm pretty shocking. What I did, especially when I came on the scene, radio was a wasteland. No one was really up to much of anything. You know, you'd even hear political commentators, they stayed impartial. I remember when I was on in Washington, D.C., and I shot to number one quickly. It was so easy because broadcasters who were, let's say on WTOP in Washington, which was an all-news station, and they had political discussion. The broadcaster never would say, "I'm a Democrat, or I'm a Republican." They stayed out of it. The audience, all of a sudden, things became heated up when I got in radio, and it wasn't enough. And I think I changed radio for the better, but I wasn't everyone's cup of tea. I can now certainly understand why.

Smith: So, what do you say to those folks who just dismiss you as this vulgar guy, "I'm not gonna read his book because he's that, you know, potty mouth guy"?

Stern: Well, I'd like to say to them that I think if they read this book, which is about this part of my career, psychoanalysis, family, and it celebrates some of the most accomplished people in the world, and some of the most infamous people. I've included Harvey Weinstein, Bill O'Reilly, and I struggled with that.

But I put in our president. There's wild conversation with Donald Trump and A.J. Benza on my radio show. But there's also a lot of people in this book who have built incredible careers, and you can learn something from 'em. What was it that drove them? What are some of their thoughts? What are they struggling with? There's a lot of human drama in these conversations. And so, I would make an appeal to them to read the book, and maybe it's self-serving. Of course it is! But I really wrote it, I really can honestly tell you, (LAUGHS) I didn't write it for the money. I wrote it because I'm proud of it, and I think they'll get something out of it. As book readers, I think book readers will enjoy this, I truly do.

Smith: You dedicate the book to the animals that you and Beth have rescued. Why?

Stern: Because this is really opened up my heart, too. I wrote a touching piece about my cat, Leon, who I've painted many times. I paint cats a lot. I do watercolor paintings. And the one in the back of the book, I put a watercolor painting of my cat, Sophia, I did gazing out my window. And Sophia died young. But my wife got me into animal rescue. I always had a love of animals, but she decided her life's passion was to open up our home. First we got involved with North Shore Animal League, and we raised the money to build a new wing, which is a cage-free environment for cats, and free up room for dogs. So, they have a better experience in shelters.

And then we started to open up our home, and Beth created an Instagram account, where we started to try to adopt out some of these animals. And people started following her, and now we've had over 1,000 cats come through our house, and we've gotten homes for all of them.

Smith: A thousand cats?

Stern: Yeah, Fart-Man now helps cats. (LAUGHS) So, it's pretty amazing, over 1,000 cats.

Smith: It's astounding.

Stern: Right now, I have three pregnant mama cats in my house, and we give them a safe environment. They don't have to be in a cage. We feed them, they have toys, and then these great people, we vet them, we do the whole thing. And then we find them the best home we can find. And I gotta tell you, it is heart-wrenching. Because each one of them, we want to keep. We fall in love with these animals, and we're so worried that when they go to someone's home they're gonna leave a door open. We don't believe in putting a cat outside. And what I obsess, I worry about them.

Smith: About the cats?

Stern: And so, oh my God, yeah, because I'm so emotionally attached to them.

Smith: What do you think that's done for you?

Stern: Oh, it is so rewarding to get involved with animal rescue. I can't tell you, there are times where I'm sitting there and it's all about me, and I'm worrying about an interview, or I'm worrying about the radio show, or you know, whatever it is. And I have to, like, literally say to myself, Go downstairs with Beth, and just sit with the cats.

You get out of your head. And I can sit in a room all day and paint, and play chess, and I can entertain myself. I'm not a person that's bored. But in order to integrate back into the world, I go and do the animal rescue. And we've done all kinds of animal rescue, dogs, birds, everything. We stopped eating meat, and we stopped eating birds after this. We'd be hypocritical. But yeah, I love it. And I love my wife for turning me onto that, and I love how she is with animals.

Smith: Yeah, how much of this evolution is because of Beth?

Stern: Oh, so much of it. I mean, I've never felt so loved, and I've never been so in love with someone. My kids were my first real love affair, but my relationship with Beth has been so healthy, and so good for me. And she's so opposite me in so many ways, that I hold her up as a role model. You know, I really do. I learn so much from her. Like, as you can tell, I'm constantly talking. It's like an umbilical cord that I need to form with people. And she is not like that. Like, we were at dinner last night, and she was very quiet. And I got so uncomfortable. To me, if someone is constantly talking – oh, they don't love me, they don't this, they don't that. And it shows me you don't have to constantly have that umbilical cord. And she's so at peace. She'll sit there with a cat on her lap and start cutting their nails. I can never do this. And you know, she's just so calm, and her presence is just so magical to me, that I just feel very fortunate that someone like that could love me. Which is phenomenal. So, all of this is important to becoming a better interviewer. So, you have to marry Beth, have to go into psychoanalysis four days a week. Well, you know, look, you know, I'm sitting here actually thinking, Oh, I would love to talk to you about how you got in the business.

Smith: No, you can't ask me questions.

Stern: No, I know. And it's very difficult.

Smith: I know, I know.

Stern: Because I'm really kind of curious about how you got started.

Smith: No, no, no. We have to talk about another – I think it's fair to say, love, Robin?

Stern: Oh my God, Robin. Robin is something else.

Smith: So, she had her own health battle with cancer?

Stern: Yeah, I remember telling Robin my thing, I was scared about going in for this kidney operation. It's a crazy operation, they use seven robot arms, and you wake up, and you look down, and you go, Oh my God, you know? (LAUGHS)

Smith: Jeez.

Stern: You know, it's crazy. And it took me a long time to get back in the groove. By the way, that's another reason I didn't want the calling in and going, "Oh, you sound worn out, or you sound tired, or you sound – " or reading into it. So, if I had a s***** performance or a bad performance, I would somehow be evaluated in light of what had happened to me. So, I kept it quiet and nobody noticed. With Robin, kind of the same thing.

You know, Robin is going through this horrible health scare, and she has fought cancer so bravely. You know, when people used to say, oh, someone's so brave, I didn't even know what they were talking about. Robin is such a force of nature, and so positive, that the way she tackles her illness, to say it's inspirational would be trivial. Like, it literally is amazing.

And we've become much closer especially after her illness. And in talking with her, and going through it with her, it even reminds me every day of how important she is to this show, and to me personally. She has been everything to me. The day that a program director named Denise Oliver teamed us up in Washington D.C., I felt complete, in terms of my performance.

Robin and I never saw each other when we got hired. We talked on the phone. That was our audition. It was my way of hearing if we had something. And all of a sudden on that one phone conversation, I go, Holy cow, is this easy! She's my muse. She's like my audience. I'm not a standup. I don't have an audience in the studio. She's literally the person that I'm talking with and hearing feedback from. And her brilliance has been nothing short of phenomenal in my career. My father used to always say to me, he goes, "Robin's the right person." She's a wealth of knowledge, she's able to interject and keep me going. You know, I've got to fill 4 1/2 hours every day. So, Robin is all of that. And when it all of a sudden happened, materialized, she had this cancer, a tumor, I was like, I can't lose Robin. I can't. She's had my back every step of the way, and I've had hers.

Smith: Did you allow yourself to think about, what if I lose her?

Stern: I cried, I cried like a baby. It was horrible. She had a 12-hour surgery, her first big surgery, and she has a girlfriend, who is in the medical community. She would call and give me updates, and at one point right during the surgery, during this 12-hour period that was a real scare, I just lost it. I just lost it. I couldn't control myself. I was like, "Oh my God, Robin, I'm gonna lose Robin." I couldn't imagine my life without her. I don't know that I would even continue to do a radio show if I lose Robin. I don't know how that would look. She's the most fantastic collaborator. She's part of the sound of the show. I describe in the book, many times the only way I can listen to the show is, I go in a shower, and I have a speaker in the shower. And I listen to the show, and I listen to our voices. And if it sounds a certain way, I can't hear the words, all I can hear is the modulation of the voices. And sometimes it sounds like radio to me. It sounds the way I hear it in my head. And I go, Oh okay, the show's fine. I don't need to hear the actual content.

So, Robin has to stay alive. I told her that. I tell Robin all the time what she means to me. But it even feels like I don't tell her enough. So, it's a tremendous relationship. It's been a tremendous success as broadcasters what we do. And I think we both really have come to a place where we genuinely appreciate each other, not only as performers, but as people.

Smith: Well, it sounds to me that part of this evolution is allowing yourself to get close to other people?

Stern: Yeah, yeah, I'm able to tell people what I think of them, and how important they are, without feeling ashamed. And that's a whole other long story, but I'm able to open up, and not be afraid of feeling attachment. For so many years I was afraid to feel attachment. It's a weird thing. You're so well-protected when you don't feel attachment. Nothing touches you. And now, with the thought of ever losing Robin, for example, that touches me and that's painful. And I was afraid to be in pain. And now, I'm open to the idea of being a human being. (LAUGHS)

Smith: So, who's the big dream interview now?

Stern: Well, quite frankly, you, I'm going to say.

Smith: Yeah, right.

Stern: Yeah, no. What the dream interview would be, you know, it's really weird. It's not always who you like, it doesn't have to be the biggest name. Sometimes the dream interview is talking to this guy, J.D., who works for me, about what's going on with his wife. Everyone is interesting, and I learned that when I was a really young broadcaster in Hartford, Connecticut. I was in charge of their public affairs programming. Not only was I the morning man, not only was I the guy who was in charge of making commercials. But on Sunday mornings I was in charge of – this is how I believe you've got to put in your 10,000 hours to be a good broadcaster – I was in charge of their public affairs programming. So, what do you do in Hartford for public affairs? I would interview the local car dealer, or a cop, or somebody, mostly clients of the station it turned into, about their lives. And I remember my parents for some reason, I guess they had driven through Hartford from New York, they heard me on Sunday morning doing an interview with, like, a car dealer. And my mother was like, "Wow, you're a really good interviewer. This was really interesting. I really loved this."

And these were just, you know, regular people. And really, the success of the show has been, we have a thing called "The Whack Pack," just talking to guys who live in trailers, like Jeff the Drunk.

Smith: Tan Mom?

Stern: Tan Mom. Tan mom is a great guest. (LAUGHS) As good as Donald Trump.

Smith: Everyone's interesting.

Stern: Whoever's interesting, whoever, conspiracy theorists are great. But, I mean, if you were gonna talk in the celebrity world, sitting down with Mick Jagger would be pretty awesome. I wish I could've met John Lennon. I idolized John Lennon. But getting to talk to Paul, I idolize him, or Ringo, fantastic, love the Beatles. I love musicians. I love talking to musicians. They perform right in this area.

And when we built this studio, by the way, don't even look at this studio as what real radio is. This was after years and years of a career where I got to build and design my own studio. This is the dream. This is exactly how I want [it]. Everything from the piece of glass over there, to how this board, I work my own equipment, I sit behind there, and I do my thing. And everything is tricked out the way I want it. And so, even where the musicians perform and where I sit, and how I look at them, this is the Mac Daddy of all radio studios.

Smith: So, how long are you gonna do this?

Stern: I don't know. I have two years left on my contract with SiriusXM, and I am in love with the people I work with, and work for. This is the best management. They leave me alone. I haven't seen 'em in days and months! And they get me. They get me on such a level. This is such a phenomenal experience, that I wish I was 20 years younger, and had the energy to keep doing this.

Smith: Well, that's a good point. Do you toy with the idea of retirement?

Stern: Yeah, all the time. I'm someone who's never bored. I can go up to my room by myself. I spent a lot of years in Roosevelt [Long island] sitting by myself. (LAUGHS) And I can paint, I love to draw. I fantasize about being able to do that all the time. I love just sitting and reading the paper. You know, I could easily entertain myself. But then the panic sets in. Like today, I was watching the news, oh, Gayle King, the Gayle King story. I got a bit in my head for Monday's show with Gayle King and her negotiation. It's gonna kill! I've heard it already, it's good. I know it's good. So, I quickly wrote that down before I was coming here, and I sent it in to the guys, so they can pull some stuff for me that I need for that. But I can't wait to get on the radio and lay that out for my audience. They're gonna love it. They're gonna be laughing their butts off. I know that.

Smith: And that's how you are, you can't wait to get on the radio?

Stern: That's what I mean. So like, okay, I've had this in my life, my entire life. I've been dreaming about being on the radio since I was five. And I'd see the way my father looked at radio performers, and I only wanted to be that to him. So, the idea that come Monday, I can get on the air and do that bit; that's a big rush for me. You know, when you dream up something in your head, and (SNAP) quickly you can do it? I can do that. That's phenomenal. And I can do it in front of millions of people.

You know, at Sirius XM, we now have 33 million subscribers. Figure, let's be conservative, two people per subscription. Let's say there's 66 million people. They tell me, 60% of our subscribers listen to me. That's a lot of millions of people, and we're growing every day. We just got Pandora. That's gonna be a big boost.

This thing that everyone said, I was crazy to come to: They only had 200,000 or 300,000 subscribers, XM was gonna consume us. It was a stupid move. Now, we're up to 33 million paid subscriptions, and growing. If that's not a legacy for me, I don't know what could satisfy me. That should be enough.

Smith: Is that enough?

Stern: Oh, we don't know. I'll bring it up in therapy, and we'll find out. (LAUGHS) It has to be enough. It just has to be enough. And what's great about it is, it has created work for so many broadcasters. My fellow broadcasters would say to me, "You know how I hear women say, 'Oh, she's not a friend of women, she attacks other women?'" For me, my fellow broadcasters were saying, "Oh, you're a traitor. How could you go to satellite radio? Why are you not, blah blah blah blah?" I go, "Because I'm creating jobs for you, too, you moron." (LAUGHS) I mean, what are you talking about? There's more places to work. This is a good thing. And now, it's come to fruition and I love it. And so, working here is a dream job. But in two years I've gotta make that decision, do I walk away? And I don't know. I don't know what's gonna be. I honestly don't know myself. I don't know that I can really believe in the quality of the show. Would I be as effective at that point, two years from now? I don't know. I gotta really think it through.

For more info:

- "Howard Stern Comes Again" by Howard Stern (Simon & Schuster), in Hardcover and eBook formats, available via Amazon

- howardstern.com

- Howard Stern on SiriusXM

Produced by Gabriel Falcon.