Extended interview transcript: Rosanne Cash

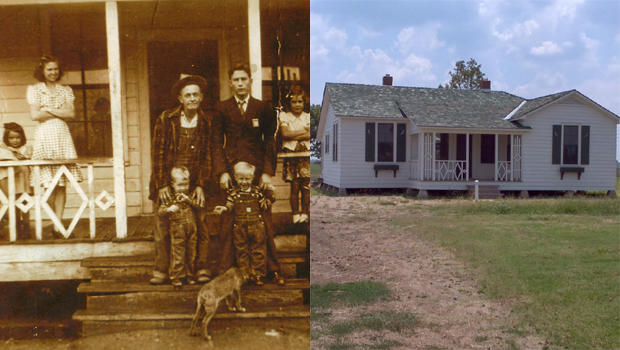

In her new album, "The River & The Thread" (Blue Note Records), Rosanne Cash explores the landscape of the Southern U.S., and the landscape of memory. Her songs are inspired by the lives lived by her father, singer Johnny Cash, and his family growing up in a cottage built under a New Deal program at Dyess, Arkansas.

The small five-room building has recently been restored by a team form Arkansas Statue University, as part of the Historic Dyess Colony initiative. Correspondent Anthony Mason accompanied Rosanne Cash on a visit to her father's boyhood home, and in this web-exclusive, extended interview transcript, they talk about her father's origins, and her own.

WEB EXTRA: Sample streaming audio of tracks from Rosanne Cash's "The River & the Thread" (Blue Note Records) by clicking on the audio embed below. You can also explore the album on Spotify (registration required), iTunes and Amazon.

ANTHONY MASON: So, how many rooms are there, actually, in the house?

ROSANNE CASH: Five rooms. And the potential bathroom.

MASON: This never really quite came [with] running water or anything like that?

CASH: No, the plumbing was never hooked up.

MASON: How old was your father when he moved here?

CASH: Three years old, in 1935.

MASON: And what exactly was this at that time?

CASH: This area was nothing. It was just empty land. And it was during the New Deal. FDR , the WPA created this colony here of 500 cottages. And they each got land and seed. The Cash family applied and out of, you know, 1,500, couple thousand families, they got a cottage. They came from Kingsland, Arkansas. My dad said when they moved in that his first memory is coming to the house and seeing five cans of paint in the front room, in this room, and this freshly-painted new home. Made quite an imprint! (laughs)

MASON: Yeah. It was a big deal.

CASH: Huge deal. They were so poor. They would not have made it without this.

MASON: And then what came with the house in terms of land?

CASH: I was told that they got 20 acres originally. And then they realized that it was not enough for them to get a good crop and pay back the government for what they got, the house and land. So they got 40 eventually.

MASON: When was the first time that you [saw this place]?

CASH: I was 12 years old. It was empty and we walked around the house looking in the windows. And I sensed this not quite longing in my dad. But a kind of sadness. And the 12-year-old didn't really assimilate what that was about. I always knew we had this connection to where he grew up, and to this particular house. And he was intensely proud of that, that he worked the soil and he came from, you know, a hard-working family.

But there was also a sense of loss, you know, tremendous loss, 'cause he lost his brother here. He was his best friend and his hero. He said something in a letter to my mom when his family sold the house, he said, "Every rock means something to me." And it did, you know?

MASON: It must have been huge, to pick your whole family up and move them to this new town.

CASH: But they were so excited. I mean, this was salvation. (laughs) This was going to save them. The fact that they were chosen, that they could get this house and land. And all of these 500 families who came here, you know, and built something out of nothing and made a community. And, you know, they survived. They survived.

MASON: Which wasn't easy, based on everything that happened.

CASH: No.

MASON: I don't know how much thought had actually been put into this place here, considering the flood and everything.

CASH: Well, yeah. And that the land was not easy to till. It was called gumbo soil. (laughs) And it was like gumbo. It was all, you know, like tar, it was very hard. And they had to dig out the tree stumps and the boulders. And some families gave up, but the Cash family stayed. They persevered.

MASON: That's the definition of perseverance.

CASH: Yeah! (laughs)

MASON: Okay, what room is this?

CASH: This would've been my dad's bedroom. He would've slept here with his brother, Jack. And then Louise and Reba would have been in here as well. Four children in this room.

MASON: Four children in this one space.

CASH: Yeah. And original linoleum in here, too.

MASON: Wow. -

CASH: A lot of Brooklyn hipsters would pay a lot for this! The team has been so meticulous about restoring it exactly as it was. Most of the wood's original. And it's a cold day. Feel how cold it is in here.

MASON: And that's how cold it would have been in the house back then.

CASH: Yeah. Kerosene lamps. No electricity and no running water. (laughs) When I think about how hard my grandmother's life was, you know, that's what my song "The Sunken Lands," I wrote about her. 'Cause she picked cotton, she raised seven children, she cooked, she cleaned. She did the work of the men and she kept the house and the children.

I mean, that work was almost medieval, it was so hard. I don't think we can imagine. And she did it all without electricity or heat.

MASON: How did your father describe this house?

CASH: I think it was more than the house, it was his connection to the area and the earth. He was proud of it. This was the greatest thing he'd seen when they moved in. He was a small child You couldn't believe it, it was a mansion. Brand new house, freshly painted. Pretty linoleum on the floor.

MASON: This is the bathroom over here?

CASH: Yeah. They didn't have running water. So there were two holes in the floor. And they pumped water up into the bathtub and then drained it in the hole below. So there was an outhouse. There was never a toilet in here. (laughs) Did I mention how hard the life was?

When I came here when the restoration was almost done, I went in this room, my dad's room, and they told me where his bed was, which side. And so I stood there and I thought, "I can stand here imagining him as a child sleeping there. What if he could've imagined his middle-aged daughter walking into this room and standing right where he slept as a child?" It just felt like the oddest sense of time travel. Like the thread that connects you to the past. And in my mind, I imagined he would've been pleased, you know?

MASON: I'm sure he would've been.

CASH: And that his daughter came back to see where he grew up. This whole experience has been like that for me, though. Like time travel.

MASON: 'Cause you heard about it your whole life, and to suddenly see something that you've heard about.

CASH: And for it to come to life. It was almost gone. It was almost in the ground. And it's come back to life. A team at Arkansas State brought it back to life. And it was one of few that survived. There's only a handful of these cottages left.

MASON: It's a miracle that it's even here.

CASH: Yeah. Yeah. Wow, it's a miracle we're here. (laughs)

MASON: Okay. This is the kitchen here. What was this like then?

CASH: Well, it's pretty much as it was. I mean, this was the sink exactly. And I wish I had that sink in my apartment, actually, it's so great. (laughs) And my grandmother cooked for a family of nine on this stove. And my grandmother was standing at this sink washing dishes one day when she heard this voice singing. And she looked up and she said, "Who is that singing?" And my father was singing "Everybody Wants to Have Religion and Glory" in this deep voice -- his voice had changed. And she said, 'son, God has his hand on you."

MASON: And that's when she knew he had a career.

CASH: Well, she knew he had a voice, anyway. (laughs)

MASON: It really -- it's hard to have a career in those days.

CASH: Yeah, I don't think they had a concept of a career. That wouldn't have come in [the picture]

MASON: You were talking a little bit [about when] you came back here to see what they were doing with this place, like, a year or two ago?

CASH: I first came back in 2011 when the man they bought it from was still in the house. And it was pretty dilapidated. It was in dangerous condition. It was kind of a perfect storm, really. I came back to see the house. And then for the first fundraiser we did for the restoration in Jonesboro -- it was this beautiful show, big show, Kris Kristofferson and George Jones and all these fantastic people. And Marshall Grant, who was my dad's original bass player in the Tennessee Two and who I was very close to, he came to the rehearsal that day. And he was going to be in the show that night. He played his big stand-up bass at rehearsal. And he had a brain aneurysm that night and he died.

And I was talking to his wife Etta, who was his wife of 65 years, which I think is a record for a touring musician. (laughs), and she said, "You know, every morning we woke up and said to each other, "What's the temperature, darlin'?" You know, just this practical way to start the day." And I told John that story. And he said, "That's the first line of a song."

MASON: Uh-huh. And then it became a series of songs about this journey for you.

CASH: Yeah. Well, the next song was "The Sunken Lands," about this house and this land and my grandmother. The hero of that story is my grandmother and how hard her life was. She didn't have any of the things that modern women -- you know, friendships, lunches, those kinds of things. That didn't exist. (laughs)

MASON: Almost unimaginable in that.

CASH: Well, I'm sure she had friendships but, you know, it was all-around hard work. And church. And music. The radio. So some of the songs on the record came from that, and then "50,000 Watts," about the radio being the common prayer of all of us. Back then it was a lifeline.

MASON: But what strikes me in the album and in the music is, even though many of them [were] precipitated by different moments in traveling the South, it pops up in a number of songs that you've taken a trip back here.

CASH: Yeah.

MASON: After essentially having been gone for a while.

CASH: Well, you know that T. S. Eliot line, "We arrived where we started and we know it for the first time"? That's kind of what happened to me. I thought that the South, and my Southern connections, were something that was, you know, vague and in the distance.

And when I started coming back here, not only Marshall's death and coming to the house, which was incredibly powerful, and walking into that room where my dad slept as a little boy. And thinking about, could he have been thinking about his daughter walking into that room? But going to Florence, Alabama, to visit my friend Natalie, who has a workshop there of hand-stitched clothing. She's like a sister to me. And she taught me to sew. And on one of these trips she was threading my needle. And she said, "You have to love the thread." And she wasn't speaking in metaphors, you know. But it chilled me, like, backwards and forwards, you know. You have to love the thread. (laughs) And we drove through Mississippi that day and on to first Alabama, then Mississippi, and onto Memphis, and then back up here to Arkansas.

And I was thinking about that line all the way. And how all through our lives growing up we take these long excursions away from ourselves. These escape routes. We create these escapes and we push away the things the hardest that we end up embracing the closest later on. At least, I've found that to be true for myself. So to come back to the South and to see it with open eyes and a full heart, it's been a powerful experience.

And an album came out of it.

MASON: What's the next to the last line or the last line in "Money Road"?

CASH: "We left but never went away." And it never went away for me, either. (laughs)

MASON: But see it's funny, "cause in some ways it feels like you tried to make it go away.

CASH: Sure. In the same way you push your parents away when you're growing up. You wanna find out who you are. You push away a lot of things. Your parents" habits. The things they treasure. You go, "Well, that's not me. I'm original." (laughs)

We all think we're original. But discovering those things that really connect you to the past and your parents and where they came from --

MASON: You feel stronger for it.

CASH: I feel stronger for it. I feel whole for it. And I also feel a better parent for it, oddly. Like I can show my children their own lineage, what they come from. What's important to me. And hopefully when they stop pushing me away (laughs) it'll be important to them.

MASON: But, yeah, they'll have to make a long trip, too.

CASH: Yeah. They'll take the long way home, whether they want to or not.

MASON: Yeah. That's the other line that I noticed in the album: "They took the long way home. You list all the places you've gone.

CASH: Yeah. Well, also, Anthony, you know John's a native New Yorker. We co-wrote the record. He wrote, you know, 90 percent of the music, I wrote 90 percent of the lyrics. And that 10 percent we got into each other's territory was mostly because we were complaining. (laughs) But I don't think that we could've written this had we lived in Dyess, Arkansas, or in Money, Mississippi. I think it required a lot of journeys to get back, and some perspective.

I'm so open to it. I love it. I love the people. I love this land. Because I am a part of this even. You know, the Cash family survived because of this land. Because of those fields. So I survived because of that, then, too, you know?

MASON: Uh-huh. It's funny, sometimes it takes a long time to see that.

CASH: Oh. Takes a lifetime.

MASON: One of the things that's so nice about the album is that there seem to be a lot of these moments where you get hit by something. And as I say, you have to be open to being hit by something. To be hit by it. But it feels very rich.

CASH: It is rich. It's dense. It's rich to the point of being dense sometimes, you know. And this part of the country, you know, the Delta and the flood plains and the music that came out of this, and the revolution. I mean, the Civil Rights era began. And it's hard to understand how so much of what is quintessentially American came from right here. You just have to wonder what happened in the Delta. What is it about the Delta?

MASON: As you started writing these songs, what were you thinking about what was coming out?

CASH: After we wrote "Etta's Tune," the first song, we started talking about writing an album about the South. Not just my feelings about the South but about the real sense of time and place and the characters. And the geographical journeys as well as the spiritual journeys. Not just travel but time travel, too, you know? All of it.

And any time I would drift too far into writing too much from my own feelings about it, John would pull me back and go, "No. Write in the third person. Write about the land, the sunken land." And I have a friend, Ted Rollins, who's very close to my family. And he said, "Dude," -- he calls me Dude! -- "you gotta write a song about the five cans of paint." 'Cause that story my dad told many times. So "The Sunken Land" begins with five cans of paint. And it was challenging, but what good thing is not challenging? (laughs)

And then the last song, when we got to Money Road and Mississippi we were driving away. And John said, "We gotta write a song about Money Road." And that ended the record.

MASON: Love that song. It kind of ties everything together in a way.

CASH: Yeah, it does. In the way that "A Feather's Not a Bird" lays out the landscape for the album, "Money Road" finishes it. We left but never went away.

WEB EXTRA: Sample streaming audio of tracks from Rosanne Cash's "The River & the Thread" (Blue Note Records) by clicking on the audio embed below. You can also explore the album on Spotify (registration required), iTunes and Amazon.

For more info:

- rosannecash.com | Tour information

- Follow Rosanne Cash on Twitter and Facebook

- Rosanne Cash's photos on Instagram

- "The River & The Thread" by Rosanne Cash (Blue Note Records)

- "The River & The Thread" streaming sample tracks (Soundcloud)

- For more on the album visit iTunes or Amazon

- "The River & The Thread" Map on Pinterest

- Historic Dyess Colony, the Boyhood Home of Johnny Cash, Dyess, Ark.