Explaining the visa program Donald Trump is targeting

NEW YORK — President Donald Trump is targeting a visa program cherished by tech companies for bringing in programmers and other specialized workers from other countries.

These visas, known as H-1B, aren’t supposed to displace American workers. But critics say the program mostly benefits consulting firms that let tech companies save money by contracting out their jobs to foreign workers. The White House has also said the program drives down wages for American workers.

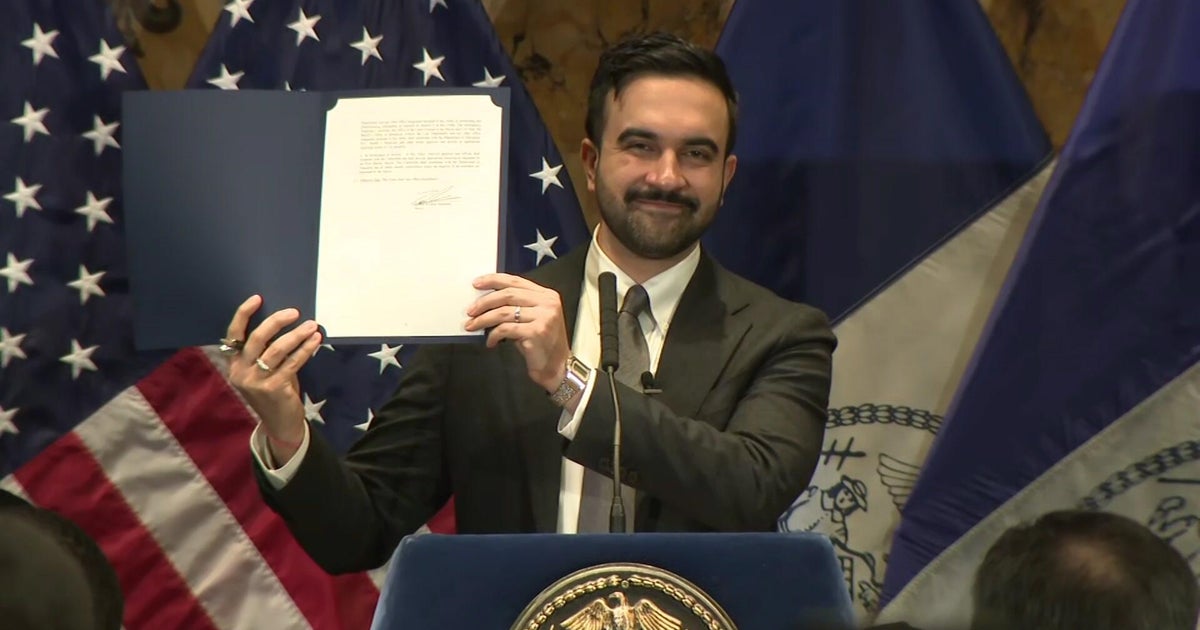

Mr. Trump signed an order Tuesday directing the departments of Homeland Security, Justice, Labor and State to propose new rules to prevent immigration fraud and abuse. Those departments would also be asked to offer changes so that H-1B visas are awarded to the “most-skilled or highest-paid applicants.”

Here’s a look at how the H-1B visa program works.

Is this a tech visa program?

The H-1B program is open to a broad range of occupations, including architects, professors and even fashion models. It’s meant for jobs requiring specialty skills that cannot be filled by a U.S. worker. Many of these jobs happen to be in tech. According to the Labor Department, the top three H-1B occupations are computer systems analysts, application software developers and computer programmers — and those three account for roughly half of the department’s H-1B certifications.

The tech industry says that companies have trouble filling positions with American workers and must turn to other countries through this program. Supporters have sought to expand the number of visas allowed each year, something unlikely to happen.

By the numbers

Although the program is capped at 85,000 new H-1B visas each year, more than 100,000 workers are allowed in annually because of exemptions for university-related positions. Recipients can stay up to six years. Demand for the visas is usually higher than the cap, so the government holds an annual lottery. This year, the government received nearly 200,000 applications for the available spots in less than a week.

What about American jobs?

By law, companies are required to pay at least the prevailing wage for that occupation. In practice, critics say companies can pay less by classifying jobs at the lowest skill levels, even if the specific workers hired have more experience. Many of the overseas workers are willing to work for as little as $60,000 annually, far less than $100,000-plus salaries typically paid to U.S. technology workers.

As a result, many U.S. companies find it cheaper simply to contract out help desks, programming and other basic tasks to consulting companies such as Wipro, Infosys, HCL Technologies and Tata in India and IBM and Cognizant in the U.S. These consulting companies hire foreign workers, often from India, and contract them out to U.S. employers looking to save money. Tech workers losing their jobs sometimes have sometimes been required to train their foreign replacements to qualify for severance packages.

In some cases, companies must make a good faith effort to hire a U.S. worker before turning to an H-1B worker, but there are many exceptions to this requirement.

Trump’s cards

The Trump administration can do a few things on its own.

A few weeks ago, the Trump administration issued a stern warning to U.S. companies that it would investigate and prosecute those who overlook qualified American workers for jobs. An official with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services also circulated a memo intended to reserve approvals for computer programming to more senior positions. Although the memo doesn’t have the force of law and is merely intended as guidance for employees reviewing individual cases, it could make it more difficult for entry-level workers to get approved.

Beyond that, the administration could scrap the current lottery approach and give priority to higher-paying jobs, thereby weeding out lower-paying, entry-level positions. Trump wants individual departments in his administration to come up with proposals.

What about Congress?

One bill, proposed by Sens. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, and Charles Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, would require companies seeking H-1B visas to first make a good-faith effort to hire Americans, a requirement that applies to only some companies under the current system. It would also give the Labor Department more power to investigate and sanction H-1B abuses and give “the best and brightest” foreign students studying in the U.S. priority in getting H-1B visas.

Reps. Darrell Issa and Scott Peters — a Republican and a Democrat, both from California— propose raising the minimum annual salary for certain exemptions to $100,000, from $60,000. The change could make even more companies subject to the requirement to try to hire U.S. workers first.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren, a California Democrat and former immigration lawyer whose district includes the heart of Silicon Valley, has proposed raising the minimum salary even higher, to $130,000. Her bill also would give priority to higher-paying jobs, while setting aside 20 percent of spots to smaller businesses, which might not be able to pay as much.