Experimental antibody drug stalls 7 kinds of cancer, study shows

(CBS News) A new study shows one single drug can stack up against seven types of deadly cancer, shrinking tumors and stopping them from spreading.

How does it work?

Prostate cancer cured in mice: Are humans next?

Antibody could help predict ovarian cancer

PICTURES: Cancer: 25 Deadliest States

The treatment is a single antibody, which is a protein used by the immune system to destroy foreign cells, like bacteria or viruses. This antibody works by blocking a "protein signal" called CD47 that's found on cancer cells. CD47 saves cancer cells from destruction by using a signal to stave off antibodies. The researchers say the antibody treatment appears to be safe and effective after testing it in mice.

"Blocking this 'don't-eat-me' signal inhibits the growth in mice of nearly every human cancer we tested, with minimal toxicity," Dr. Irving Weissman, professor of pathology who directs Stanford's Institute of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, said in a university statement. "This shows conclusively that this protein, CD47, is a legitimate and promising target for human cancer therapy."

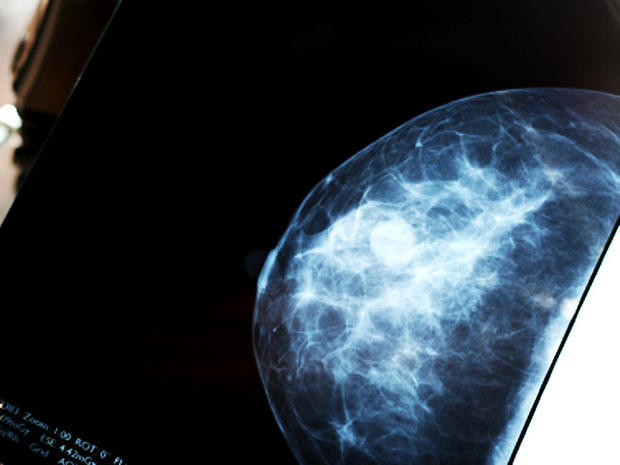

Blocking CD47 with the antibody stalled tumor growth from human breast, ovarian, colon, bladder, brain, liver and prostate cancer samples in mice. Five mice injected with human breast cancer cells were "cured," the researchers said, with no signs of tumor recurrence four months after stopping treatment. The research was published in the March 26 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

For some mice that did not see their tumors shrink, the treatment stopped their cancer from spreading elsewhere.

"If the tumor was highly aggressive, the antibody also blocked metastasis," Weissman said. "It's becoming very clear that, in order for a cancer to survive in the body, it has to find some way to evade the cells of the innate immune system."

But Weissman cautions the treatment didn't work for some mice who had breast tumor cells from a particular human patient. He also isn't sure if shrinking the tumors through radiation before antibody treatment could be more beneficial.

Dr. David DiGiusto, a cancer researcher at City of Hope in Duarte, Calif., who was not involved in the study, told the Los Angeles Times that even though the mice in the study didn't experience toxicity and side effects from the treatment, humans might.

"You run the risk of not only killing the tumor, but also the normal cells," he said.

But the researchers are eager to begin human trials within the next two years, and other cancer researchers are excited at the treatment's potential.

"This is exciting work and will surely trigger a worldwide wave of research designed to convert this strategy into useful therapies," Dr. Robert Weinberg, professor of biology at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Massachusetts who was not involved in the research, said in the statement. "Mobilizing the immune system to attack solid tumors has been a longstanding goal of many cancer researchers for decades."