How these explorers survived 56 days in Antarctica using only clean energy

Editor's note: Special thanks to our CBS News Digital partners Global Goalscast, a podcast produced by UNICEF special adviser Claudia Romo Edelman and Hub Culture executive editor Edie Lush featuring inspiring stories about people advancing a more sustainable future. Each episode focuses on a separate issue as it relates to current events and Sustainable Development Goals, such as ending poverty, combating climate change, and ensuring equality. Listen here: https://www.cbsnews.com/goalscast/

When Robert Swan became the first man to walk to both the North and South Poles, a milestone he completed 32 years ago, he thought he would never do it again. But in 2017 he found himself back on the ice, trekking 600 miles across Antarctica to the South Pole with his 23-year-old son, Barney.

This latest adventure all started several years ago when Robert, an explorer and environmental activist, attended a meeting at NASA. Barney tagged along.

"They said, 'Rob, the edges of Antarctica are disintegrating ... why is no one taking this seriously?' And rather rudely, I said 'Probably because you're being a bit boring about it,'" Robert told the podcast Global GoalsCast.

It was after that meeting that Barney came up with an idea that was anything but boring: He and his dad would walk to the South Pole again, this time using only renewable energy. If successful, theirs would be the first expedition to do so.

"He said it's time you walked again to the South Pole," Robert said. "And I remember sort of shrinking in the car thinking, 'Do I really have to do his again?' At the age of 61, it's not something that people should do."

The Swans immediately got to work planning their expedition, the South Pole Energy Challenge, which took more than four years of organizing, training, and equipment testing. Walking 600 miles in 60 days in the harshest climate on the planet is hard enough, but doing it using only clean energy is an even greater challenge. They needed energy sources that would keep them warm, fed, and hydrated without negatively impacting the environment.

They decided to team up with Shell, a company Robert had worked closely with on his previous expeditions and conservation work, to sponsor and document their trip. In the past, Robert used jet fuel to melt snow into water, boil water to cook food, and keep warm inside his tent. This time, they would use Shell-produced biofuels made from wood chips in Bangalore, India.

"When I heard about what they were doing in Bangalore with these amazing fuels from wood chips — hopefully from garbage and rubbish in the future — I said, 'Game on,'" Robert explained.

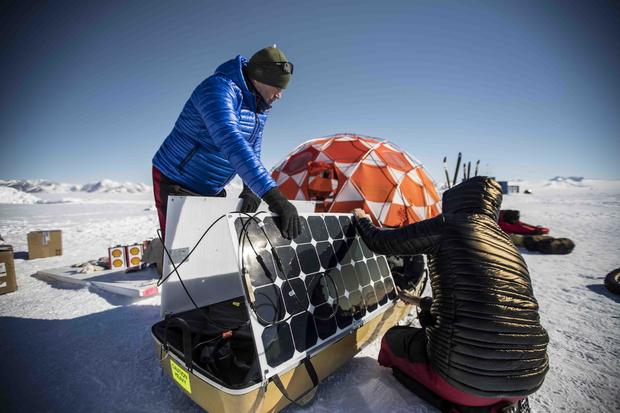

But when it came to melting ice and snow into drinking and cooking water, the biofuels were actually supposed to be their backup option for days when they had low sun visibility. Their first plan of action was to use solar-powered ice melters supplied by NASA.

"The team at NASA believe that one day these ice melters, or a variant, will be used on Mars," Robert said of the technology.

The ice melters functioned like this: Robert, Barney, or one of their two teammates would fill a container with ice in the morning, which then connected to two solar panels attached to their sleds. Over the course of the day as they walked, the ice would melt into warm water. By the time they stopped for the day and set up camp, there would be enough water ready to drink and cook their pre-packaged food using biofuels.

The melters saved both time and fuel; without them, it could take up to 60 minutes for enough drinking and cooking water to melt over their small stoves. But they were also heavy, and weighed the sleds down.

By halfway through the trip, Robert was suffering from worsening injuries and his body couldn't recover in the brutal environment. He couldn't keep up with the team, and they only had so much food and fuel left to complete the journey. They needed to pick up the pace.

He made the difficult decision to be evacuated back to base camp to heal, and to allow Barney and the others to kick into a higher gear. When he left, he took the ice melters with him to lighten their load. That meant they had to survive using solely the advanced biofuels for the remaining 300 miles of the journey.

And they did. Barney trekked on for three weeks without his dad. When he was 60 miles from their goal, Robert flew back out on the course to reunite with Barney. They made it to the South Pole on day 56 of the journey, four days ahead of schedule.

It was a personal triumph, of course, but more than that, it was an important message for the future of our planet.

"If we can survive out there only on renewable energy in the most hostile place on Earth," Robert said, "people themselves as individuals can make a difference."