Ex-priest accused of abuse seeks back pay from Milwaukee archdiocese

MILWAUKEE The list of creditors for the Archdiocese of Milwaukee includes hundreds of child sexual abuse victims, along with a bank, pension funds and others typical in bankruptcy cases. It also includes one less usual: a priest removed from the priesthood amid allegations of abuse.

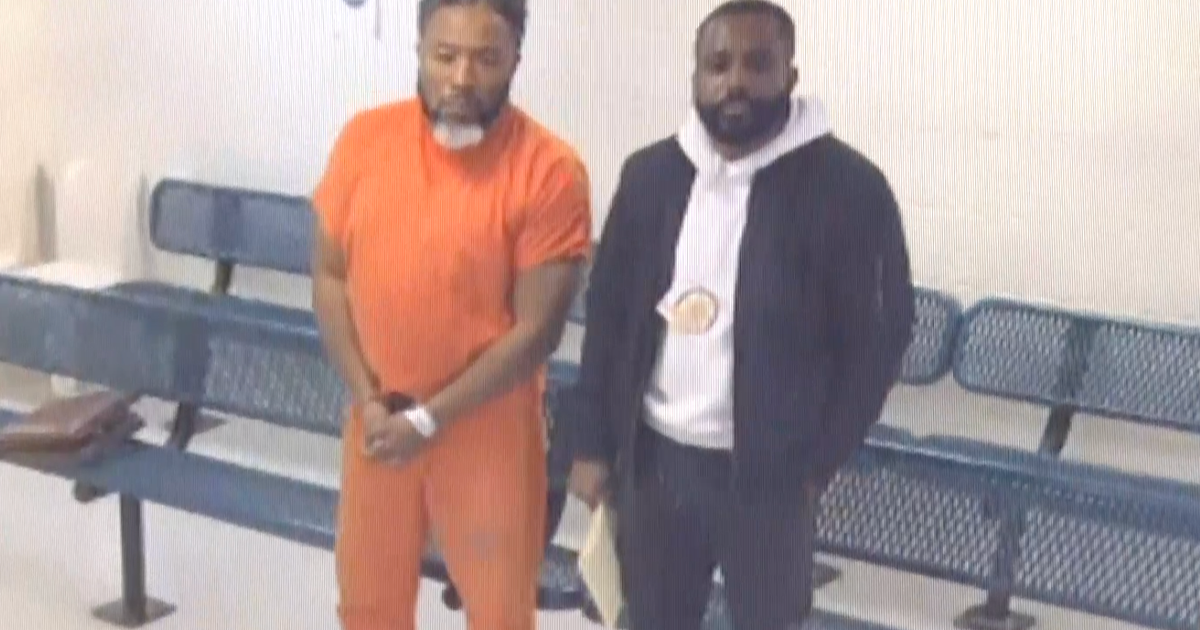

Marvin Knighton was charged with child sexual abuse in 2002 but acquitted by a jury the next year. The church still removed him from the priesthood, however, saying its investigation found two allegations against him had merit.

Knighton steadfastly fought his dismissal and has put in a claim for $450,000 for back pay from the archdiocese in federal bankruptcy court. A church bankruptcy expert said while the claim is not unique, it is highly unusual. Knighton's victims called it "disturbing" and "grossly inappropriate."

"That money should be going to survivors, not child molesters," said Thomas C. Bersch Jr., who said he was abused by Knighton in the 1970s. "During the bankruptcy proceedings, if he gets even a nickel of this money, it would be the most unbelievable thing that could happen. I wish there is something I could do to prevent that."

Attorney James Stang, who has represented sexual abuse victims on creditors councils in nine bankruptcy cases involving Catholic dioceses and religious orders, said a few priests have filed claims for back pay, health care or legal costs even when they've been credibly accused of abuse. In most cases, the claims are eventually dismissed.

- Pope criminalizes leaks, sex abuse at Vatican

- Hundreds of Milwaukee clergy abuse victims got no settlement money

- Priest sex abuse victims in U.S. look to new pope for help

The church may argue that any money it owes the priest is offset by the cost of the abuse, or "there have just been objections based on the fact that these are evil men," Stang said.

The Milwaukee archdiocese is the eighth in the United States to file for bankruptcy. Five of the other seven said no priests filed claims during their bankruptcies. In Wilmington, Del., three priests who had been removed from ministry following allegations of abuse filed claims, diocese spokesman Bob Krebs said. He didn't know the details or outcome of those claims.

The remaining diocese, in San Diego, Calif., didn't immediately respond to inquiries.

Jerry Topczewski, chief of staff for Milwaukee Archbishop Jerome Listecki, said the archdiocese will object to Knighton's claim. Knighton, 63, declined to comment and hung up when reached by telephone.

The archdiocese released Knighton's personnel file earlier this month, along with those of dozens of other priests with verified allegations of abuse. The documents showed that while Knighton had been dogged by one allegation since the early 1990s, no formal complaints were made until early 2002, when a scandal in Boston focused national attention on clergy sexual abuse.

Brian Flynn, now 39, told archdiocese officials that Knighton had abused him during the late 1980s, when the priest was on the faculty at a Catholic high school in Milwaukee and both lived in the suburb of Wauwatosa. About a month later, Bersch reported that he had been abused in the 1970s.

The Associated Press does not usually identify victims of sexual assault, but Flynn and Bersch gave permission for their names to be used.

The statute of limitations had passed in Bersch's case, but Knighton was charged with second-degree sexual assault in Flynn's case. Knighton and Flynn both testified at the 2003 trial. Knighton insisted the abuse never happened. A jury found Knighton not guilty.

New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who was then archbishop in Milwaukee, still took steps to have Knighton removed from the priesthood. In a March 2004 letter to the Vatican office responsible for clergy sex abuse cases, Dolan noted the archdiocese had received a third report of abuse and believed there could be a fourth case as well.

"After preliminary investigation, I am satisfied that these have the semblance of truth to them," Dolan wrote.

A church trial found two of the allegations, those made by Flynn and Bersch, were valid. Knighton wasn't removed from the priesthood, however, until 2011 after a yearslong appeal.

Knighton's criminal defense attorney, Gerald P. Boyle, said he still believes the former priest is innocent. Boyle criticized the archdiocese for not contacting him during its investigation.

"I couldn't understand that," he said, adding, "I have no reason to believe it was anything other than a good verdict."

Knighton's bankruptcy claim has been transferred to a federal bankruptcy trustee in Arizona, where the ex-priest filed for bankruptcy in February 2011. John Carter, the attorney for the bankruptcy trustee responsible for Knighton's case, said in an email that the claim was being pursued and any money would go to pay Knighton's debts.

Bersch and Flynn are not involved in the bankruptcy case.

Bersch, a 53-year-old business development executive who now lives in Illinois, said he settled with the archdiocese in 2004 for $40,000. He described Knighton as a warm, outgoing, bear of a man whom everyone loved. He said he was about 12 when the priest befriended him, taking him to movies, out to eat and for sleepovers before eventually molesting him.

"The only thing that's important me today is that this man never gets the opportunity to teach or be around children," Bersch said.

The Arizona Department of Education said Knighton is licensed to teach in that state but couldn't say whether he was actually working as a teacher.

Flynn said the bankruptcy is difficult because he worked hard to come to peace with what happened, and every time Knighton comes up, "it triggers the pain, and the helplessness."

"It's like this is never going to go away," he said.