Ex-hedge fund manager founds school in Somaliland

- The mission of Abaarso School of Science and Technology is to produce the future leaders of Somaliland.

- Almost 90 percent of Abaarso's first graduating class got accepted to international colleges, including in the U.S.

- If President Trump's travel ban goes into effect, the next group of Abaarso students headed for American universities may not be able to come.

In 2008, a man named Jonathan Starr was 32 years old and running a hedge fund in Boston. He was a millionaire, but he didn't like his job very much, and wanted to do something to give his life purpose. He'd heard about a desperately poor African nation called Somaliland that needed help. Somaliland broke away from Somalia 25 years ago. If you've never heard of it before, it's probably because it still isn't recognized as an independent country.

Jonathan Starr went there for a visit, and that's when he came up with a kind of crazy idea. He decided to build an American-style boarding school to help kids in Somaliland get into the best universities in the U.S. and beyond. Starr hoped his students would then return to Somaliland as doctors, lawyers, business people, and future leaders.

It's not easy to get to the school Jonathan Starr built. Somaliland's capitol Hargeisa, isn't exactly a bustling metropolis. There are few flights in, and once you're here, it's a bumpy ride on dusty dirt roads, past miles and miles of empty scrubland. The school sits on a remote hilltop, in what can best be described as the middle of nowhere.

It's called the Abaarso School of Science and Technology, a boarding school that's home to around 200 of Somaliland's best and brightest, grades 7-12.

Anderson Cooper: What's the goal of the school? What's the idea of the school?

Jonathan Starr: So the mission of the school is to produce ethical and effective leaders of the country in the future.

Anderson Cooper: Future leaders of Somaliland.

Jonathan Starr: Somaliland, Somalia. The point is they'll be future leaders in this area. And that should be everything. That should be business, government, law, health care-- and we have students studying everything. So ultimately, it should work that way.

There was no guarantee it would work that way when Abaarso began accepting students in 2009…but Jonathan Starr was determined. He'd moved to Somaliland and has spent more than half-a-million dollars of his own money building the school, recruiting the students…and hiring the teachers, nearly all of whom he found online.

Anderson Cooper: How much money were you offering to pay the teachers?

Jonathan Starr: $250 a month.

Anderson Cooper: $250 a month. To come to Somaliland.

Jonathan Starr: We cook for them; we have food for them. If they don't leave campus, they'll never have an expense whatsoever.

Anderson Cooper: But there's not a lot to do here.

Jonathan Starr: No, there's not a lot to do here.

They came anyway, mostly from America. Many had never taught anywhere before.

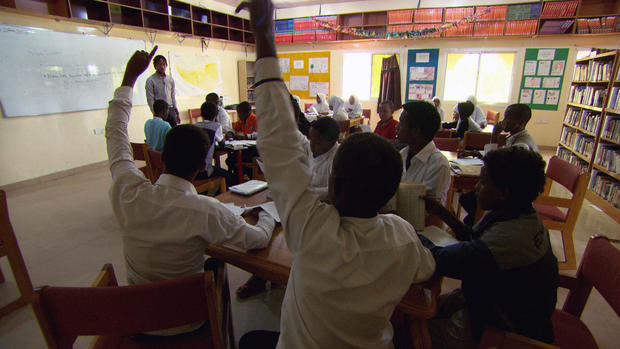

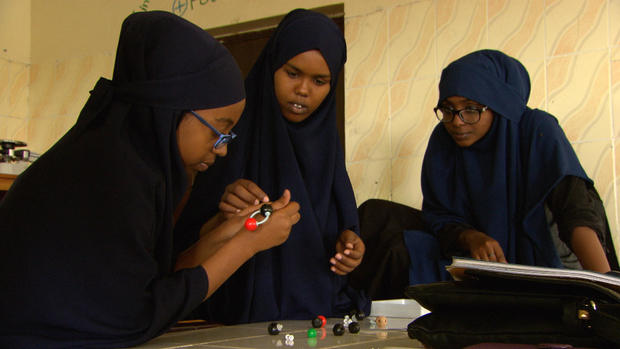

The curriculum at Abaarso is not much different from what you'd find in an American school. The intricacies of covalent bonding in chemistry, contemporary world literature, geometry, trigonometry, and pre-calculus.

But what makes it harder still is that nearly everything here is taught in English, and most of these kids only speak Somali when they first arrive. Since Starr's goal is to get students into college in the U.S. and elsewhere, he insists on English immersion from Day One.

Anderson Cooper: So how do you get somebody who-- doesn't speak any English-- and immerse them in an English-only program?

Jonathan Starr: I mean it's very, very challenging. To many of them, the transition to go from where they were to here was the hardest thing they ever would have to do. And you just have to slowly piece it together.

The school starts in 7th grade and students begin by tossing around a few English phrases.

"You mustn't, you mustn't…you mustn't, eh don't be late to class. You mustn't? You mustn't be late to class."

"Wouldn't it be fine and dandy."

Then there's reading, lots of it.

"You know something good about me, I know something good about you."

"All African countries are not poor."

By 11th grade, the kids sound like they've been speaking English most of their lives.

"How do the words, the dirty looks, roll off your backs?"

Classes begin at 7 a.m. sharp and the kids have to be on the ball all day, and late into the night. That's five and a half days a week, 11 months a year. The kids either catch up and catch on to Jonathan Starr's system, or they're out.

Jonathan Starr: We hold them to a very high standard. Every student has some job on campus and community service work. If you miss that, or if-- let's say you just skip study hall. You're suspended.

Anderson Cooper: Suspended for how long?

Jonathan Starr: That'll be a day. Students have found their way out of our school for not being disciplined, not doing the things that they've agreed to do. They know the rules of the school.

Anderson Cooper: You've kicked kids out.

Jonathan Starr: Many.

If a kid is kicked out of Abaarso, there aren't a lot of other good options. Somaliland spends less than $10 million a year on its public schools, and we saw some classrooms are crammed with as many as a hundred kids. There are few colleges here for graduates to go to.

Somaliland is doing better than its neighbor Somalia, which it separated from 25 years ago, as famine and civil war plunged that country into chaos. Somalia is still one of the most dangerous places in the world, plagued by the terror group al-Shabaab. Somaliland by comparison is relatively peaceful, though at Abaarso there are armed guards and watch towers.

Anderson Cooper: And the entire compound is surrounded with a wall and barbed wire?

Jonathan Starr: Yes, it's about 12 feet or so high

Anderson Cooper: Do you worry about security a lot?

Jonathan: We need to be. I don't think it's very likely that something would happen, but if something happened to one teacher, it could be game over for the entire school.

The real problem in Somaliland is poverty. This is one of the least developed places on Earth. The economy, like the country's biggest export livestock, is skin and bones. The main source of income is money sent from Somalilanders working overseas.

That's how most students can afford tuition at Abaarso, which is about $1,800-a-year, a fortune when you consider that the average income in Somaliland is about a dollar a day. Those who can't get money from extended family, get scholarships from the school. Abaarso has become an oasis of opportunity and every student is encouraged to dream big.

Sahra: Want to be a psychologist.

Anderson Cooper: You want to be a psychologist.

Female voice: I want to be a reporter.

Anderson Cooper: You want to be a reporter?

Female voice: So-- yeah.

Anderson Cooper: OK.

Female voice: Dentist.

Anderson Cooper: You want to what? Be what?

Female voice: Yes.

Anderson Cooper: A doctor?

Female voice: Yeah.

Anderson Cooper: Wow. Who wants to be a dentist? You want to be a dentist. Your teeth are very nice already.

It's worth pointing out just how revolutionary it is to hear teenage girls in Somaliland talk about careers. Many of these girls may have already been married off by their families if they weren't studying here. Somaliland is a deeply conservative Islamic country, and on school grounds local customs are strictly followed.

Abaarso has its own mosque, and girls and boys don't mix outside class unless there's a chaperone.

Jonathan Starr is not Muslim, but he does have a family connection to Somaliland. His aunt married a man from here, whom she met in the U.S., Starr's uncle Billeh Osman. He was the one who convinced Starr to come for a visit and do something to help.

Anderson Cooper: You didn't really know anything about Somaliland.

Jonathan Starr: Correct.

Anderson Cooper: Did you speak Arabic?

Jonathan Starr: No Arabic, no Somali. I tried to learn Somali but I'm not very good.

Anderson Cooper: It sounds like a disaster from the get-go.

Jonathan Starr: I also didn't know anything about education.

Anderson Cooper: You didn't know anything about starting a school.

Jonathan Starr: Well, I-- I had-- I'd been educated.

Anderson Cooper: I'd been to school, too, but I----still wouldn't be able to start one.

Jonathan Starr: I was a pretty good student, I had no idea I was getting into.

To help him get started, he took on a Somali partner, who talked him into building the school in this isolated spot, on land that just happened to be owned by the partner's extended family. It turned out to be a terrible idea.

Jonathan Starr: If we look out from here there is nothing, right? There's absolutely nothing, and nothing. And like, any way you look—

Anderson Cooper: Is there a water source here?

Jonathan Starr: No, there's no water source here.

That should have been a red flag. So should the name of the closest village – Abaarso.

Jonathan Starr: Abaarso-- 'abaar' means drought.

Anderson Cooper: That didn't give you pause?

Jonathan Starr: I had been led to believe getting water would be no problem at all.

The water, which is now trucked in daily, was the least of his problems. Despite all his good intentions, all the money and time he'd spent on this school, Starr was still an outsider. When he got into an argument with his Somali partner over who should run the school, he says the partner spread false rumors he was trying to convert students to Christianity.

Jonathan Starr: There were some people who had been riled up, probably given some money to do it, and came to our gates and said either, you know, I go home or they'll kill me.

Anderson Cooper: Did you ever think about going home?

Jonathan Starr: No. But I also didn't…when I say I didn't take it seriously…I was more mad than anything else.

Anderson Cooper: Why fight this fight here?

Jonathan Starr: There's the noble side, "What, am I going to abandon the students? There's no chance. There's no chance." If they were going to carry-- they were actually going to have to kill me and carry me out. Like, that actually was going to have to happen. And the second part is the not noble part, which is I'm very competitive, and there was no way I was losing to that guy. That's really the truth. I mean, if I could have somehow legally, cleanly had, like, a death match, I honest to God would have had a death match. I couldn't imagine that there was life if I let this fail.

In the end, it was his students who didn't let the school fail. In 2013, a senior named Nimo Ismail was the first Abaarso student to get into college. She was accepted at Oberlin in Ohio -- on full scholarship, no less.

Jonathan Starr: When she got in, that turned everything in the country.

Anderson Cooper: In the country?

Jonathan Starr: It turned everything. At the end of the day, people want good things for their children. And Somalis want things to root for. And they wanted to root for her. You know, they want to root for their kids doing well.

Almost 90 percent of that first graduating class got accepted into international colleges. Some 40 of Starr's students are now in American universities on academic scholarships. Nimo is finishing up at Oberlin, Fadumo's at Rochester. Her sister Nadira is at Yale, Mubarik is at MIT, and Abdisamad's at Harvard.

Anderson Cooper: Do each of you plan on going back to work somehow for Somaliland?

Nadira: I think the whole reason Jonathan doing this is for us to make sure that people back home or, like, people that are less fortunate, also get the same opportunities that we get.

Anderson Cooper: So what would be a life goal?

Nimo: I think the Supreme Court is definitely the place for me.

Anderson Cooper: Being on the Supreme Court in Somaliland?

Nimo: Yes.

Anderson Cooper: How about for you?

Fadumo: Probably, like, building a hospital and bringing a lot of equipment and bringing doctors.

Abdisimad: After, like, maybe, like, a few years working here, go back, start, like, my own business.

Nadira: Creating more opportunities for girls and seeing more girls in school.

Anderson Cooper: Empowering girls and women.

Nadira: Yeah.

Mubarik Mohamoud was part of the first class to graduate Abaarso, he is now a senior at MIT, majoring in electrical engineering and computer science.

Anderson Cooper: When you heard that you got into MIT?

Mubarik: Hmmm, yeah, that was insane.

Anderson Cooper: That was insane?

Mubarik: Yeah…

Anderson Cooper: Has it been hard?

Mubarik: MIT? It's hard, it is really hard, but the thing is, it is hard for everyone.

His English isn't as good as most Abaarso students but his story is remarkable. He was a nomadic goat herder for much of his childhood, and knew nothing about school or the world beyond his herd until he ran away. When he showed up to take the entrance exam to Abaarso, Jonathan Starr saw his potential and gave him a scholarship.

Jonathan Starr: He's pretty smart, to be fair. He has a terrific brain that just needed a chance.

The success of Mubarik and the other graduates has encouraged the students still at Abaarso to work that much harder.

Anderson Cooper: So how many of you want to go to college?

Female Voice: We all want to go to college--

Anderson Cooper: How many of you want to go to college in America?

Voices: Yes.

Anderson Cooper: You all want to go to college in America?

Voices: … (laughter)

Anderson Cooper: Any of you think you could be the president of Somaliland one day-

Voices: Of course.

Sahra: We'll try to be the ministries of education, ministries of something. And we will absolutely going to try to run the country.

Anderson Cooper: So, what's the reward for you?

Jonathan Starr: Before I did this, to me, I was a disappointment.

Anderson Cooper: You'd run a hedge fund. You'd made millions of dollars.

Jonathan Starr: Yeah. I'm not-- I'm not-- look, I definitely, like, have a bigger ego than the average human being. And I, at 32 years old, when I was first starting this, did not feel like I had lived up to that. And now I feel like I got there.

Anderson Cooper: Do you see this as something you've done? Or do you see this as something these kids have done?

Jonathan Starr: I gave them a chance to win. And then they went in that classroom and they won.

The next group of Abaarso students headed for American colleges may not get here. The State Department doesn't recognize Somaliland as a country independent from Somalia and President Trump's travel ban, held up in the courts, includes Somalia.

Produced by Henry Schuster. Rachael Morehouse, associate producer.

For more information on the Abaarso School of Science and Technology, visit their website or call 508-556-0261.tel:508-556-0261