Every year, U.S. workers lose out on billions in pay

For some workers, it means getting paid $20 for an entire day washing cars. For others, it means being paid to perform at a football game after attending mandatory rehearsals for no money. Sometimes, it's being hired to file papers, answer phones, make copies and run errands -- as an unpaid intern. Or a waitress being required to give part of her tips to a restaurant's manager.

Labor advocates call these practices "wage theft," and they hit millions of workers every year. In 2015, businesses underpaid workers by as much as $15 billion, the liberal-leanng Economic Policy Institute found in a recent report. By comparison, the total damage from property crime in the U.S. that year -- larceny, burglary, car theft and arson -- was $14.3 billion, according to FBI data.

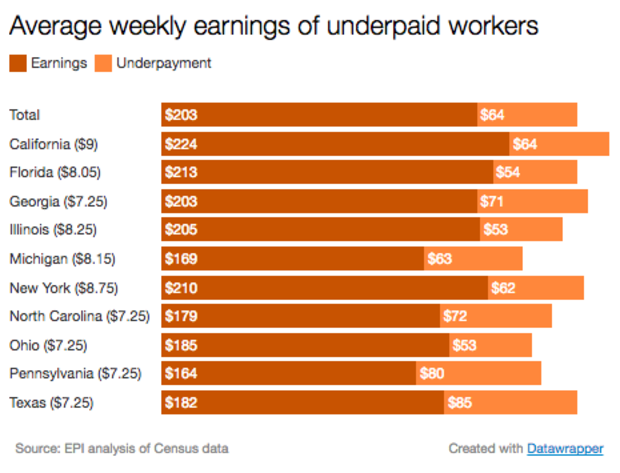

EPI, whose analysis looked at low-wage workers in the 10 most populous states, found that 2.4 million employees had been paid less than the hourly minimum wage they were entitled to under state and federal laws. That comes out to a loss of $3,300 per worker every year, or nearly one-third of a year's earnings.

Collectively, the workers covered in the report missed out on $8 billion. The states in question are home to just over half of the U.S. workforce, meaning if that pattern extends nationwide, workers as a whole are underpaid by up to $15 billion a year, according to EPI.

The report jibes with previous research, some of which found even starker examples of wages that were improperly withheld. Fully a quarter of low-wage workers in the three biggest U.S. cities (New York, Chicago and Los Angeles) were paid less than the local minimum wage, according to the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy group. The Department of Labor found that minimum wage violations in New York and California resulted in affected workers losing between 37 and 79 percent of their earnings.

The problem is especially prevalent in food service, which accounted for a quarter of the workers who were paid sub-minimum wages in EPI's report. Another 15 percent were in retail, and 13 percent in education and health. In agriculture, just under one in 10 workers earned less than the minimum wage.

"If you're not being paid what you're supposed to be, it makes the instability that much worse -- you have to decide between paying the rent and feeding your family," said Saru Jayaraman, co-founder and co-director of the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, a worker advocacy group. "Restaurant workers have the highest rates of home insecurity of all workers; you have people working full time and homeless."

Tipped workers -- including waiters, bussers, bartenders, chauffeurs or coat-check attendants -- are especially vulnerable to wage theft because the share of income that comes from their employer is small to begin with. In most states, tipped workers can legally be paid much less than the minimum wage, with the assumption that tips will make up the difference. But it's not uncommon for workers to earn less than the minimum on a slow day; to be required to spend hours doing non-tipped work, like stocking a kitchen; or to be asked to share a percentage of their tips with a manager or other non-tipped workers. In particularly egregious cases, a server or bartender can earn only tips, receiving no wage from the establishment where she works.

"The laws around tipped workers are very opaque -- they make it hard to know for employees to know if they're being paid properly. They also make it hard, in some cases, for employers to know if they're in compliance with the law," said David Cooper, a senior economic analyst at EPI and a co-author of the report.

Workers' already low hourly earnings can drop even lower if they're asked to do extra work, like setting up a workstation before clocking in, or attend meetings off the clock -- both common complaints in the industry.

Considering the federal minimum wage has lost much of its purchasing power since midcentury, being paid even less hurts workers and their families. But it doesn't stop there: Wage theft also strains the social safety net when it pushes families below the poverty line, often increasing their reliance on social services. And the billions that bypass workers also remain untaxed, and out of the pockets of businesses that cater to low-wage workers.

"I don't think most people recognize the severity of wage theft -- it's not as tangible as when someone steals from you, or property theft," said Cooper.

Still, figuring out the scale of the problem is hard because minimum wage laws are numerous and overlapping. The federal minimum wage, $7.25 an hour, leaves out many jobs and businesses; meanwhile, a number of states set their own minimum wage rates, as do a growing number of municipalities. And there are different categories of minimum wage: tipped workers, for example, usually receive an hourly wage far lower than non-tipped workers, but that, too, varies by location.

The EPI crunched the numbers by examining the Current Population Survey -- the data that forms the basis for the U.S. Labor Department's monthly jobs report. They looked at the hours people reported working and how much they earned, and compared the resulting hourly rate with the minimum wage laws in the workers' respective states and industries.

"All low-wage workers are at risk here," Cooper said.

While women and people of color were more likely to suffer wage theft, he said, it's only because those groups are overrepresented in low-paid jobs, he said. Otherwise, no demographic group is more likely to be illegally underpaid than another.

There is, however, one factor that makes it less likely a worker will be shorted: stronger penalties. Previous research backs that up. States with strong workers protection laws, such as requiring businesses that underpay workers to return three times the amount of back pay, generally have fewer wage theft instances violations. The reverse also holds true. In EPI's report, the state with the most issues was Florida -- which hasn't had a department of labor since 2002.