Etan Patz case: 1979 disappearance of NYC boy continues to haunt investigators

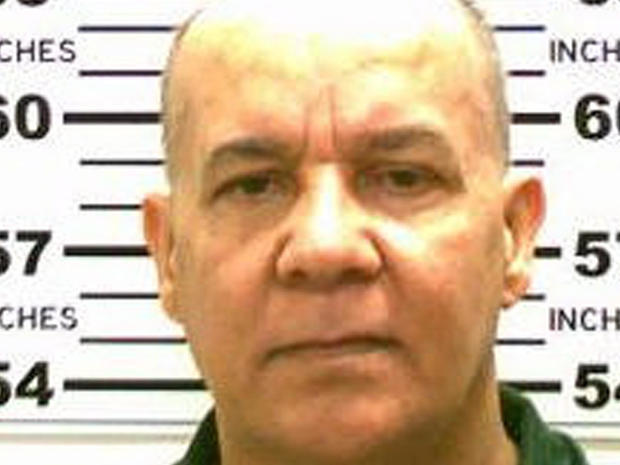

Editor's note: On July 21, 2025, a federal appeals court ruled that Pedro Hernandez must have a new trial or be released. On Nov. 25, 2025, the Manhattan District Attorney announced he intends to retry Hernandez.

This story originally aired on April 14, 2018.

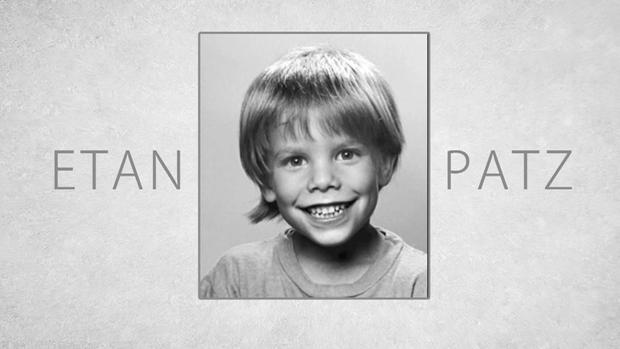

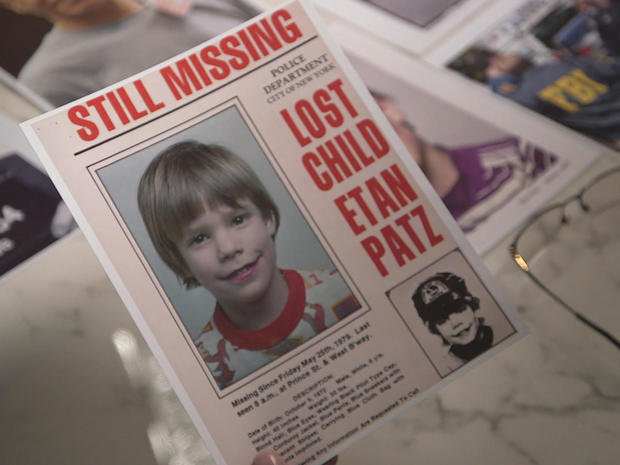

Etan Patz walked out of his New York City home headed for a school bus stop just two blocks away. The 6-year-old never made it to school that day in 1979 – and he's never been found.

His disappearance is a story that shocked New York City and to this day haunts law enforcement investigators who have spent decades trying to find him. The disappearance of the young boy is more than a missing person's case. Indeed, it changed the way parents watched over their kids.

"I think this was one of the most significant unsolved cases in the history of New York City," Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. tell "48 Hours" correspondent Richard Schlesinger.

"Every missing child case is very important, but this was one of the oldest ones we had," says NYPD Lieutenant Chris Zimmerman.

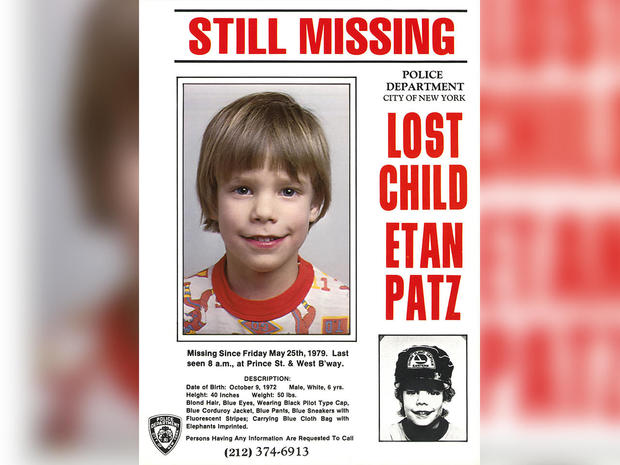

Etan Patz disappeared at a time long before social media and every storefront had a video camera. He had asked his parents to let him do the short walk to the bus stop alone for the first time. He had a dollar to buy a soda at a corner deli. His parents were unaware he was missing until he didn't return home after school. Since then, Patz's smiling image used on missing person's fliers is seared into the minds of people around the country.

"That photo will always haunt me. And every single day that I sent my son out to school, I thought of Etan Patz," says attorney Brian O'Dwyer. "And I was one of eight million New Yorkers like that."

Police began searching for Patz by going door to door. Over the years, the case would grow cold. But there was one neighborhood man police suspected of being a pedophile, whom they had their eye on almost from the beginning: Jose Ramos. Ramos, according to law enforcement, had said he took a child back to his apartment and molested him. Ramos told them he was 90 percent sure it was Patz. The case against Ramos, however, lacked corroboration, and never moved forward, says Vance.

Vance vowed to take a fresh look at Etan's disappearance when he took office in 2010. "I was on the hunt for the Patz family to find the killer," he says.

Then in 2012, the NYPD got a tip from a relative of Pedro Hernandez, saying Hernandez had talked about hurting a boy around the time Patz disappeared. During questioning by police, Hernandez told them he choked a boy. He later took them to locations near the Patz home. Was Hernandez telling the truth?

"The facts of that confession make no sense," says Hernandez's attorney Harvey Fishbein. "He's unreliable because of his psychiatric condition."

What happened to Etan Patz?

THE SEARCH FOR ETAN

After more than 30 years, it took a new team of investigators and a new prosecutor to breathe new life into an old case – trying to find out what happened to Etan Patz.

District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr.: You really should never close the book on a case if you think there's the possibility that it can be solved.

In 2012, investigators were literally digging for clues just blocks away from where Etan was last seen. After thousands of dead-end leads, the public held its collective breath hoping, this time, the case might finally be solved.

Etan Patz was just 6 years old, and like many kids that age, he wanted some independence. It was 1979, the last day of school before the Memorial Day weekend, and Etan's mother, Julie, finally agreed to let Etan walk alone to the school bus stop. It was just two blocks away from their Manhattan apartment.

Julie Patz | Etan's mother [1980]: Yes, I wish I hadn't let him go to the bus stop that morning alone. …My feelings that morning were very positive about his going.

Etan was carrying a book bag and a dollar to buy a soda at a corner store near the bus stop – and then, he seemed to vanish.

Julie and her husband Stan didn't realize their son was missing until that afternoon when he didn't come home from school. Julie called the school and learned Etan never arrived and his friends never saw him at the bus stop. So she called the police.

Patrick Eanniello | Former NYPD detective: I didn't wanna start with something bad happened to him … I would rather start in my mind, in my heart, that it was just a missing person.

Former NYPD Det. Patrick Eanniello immediately headed to the Patz's home.

Patrick Eanniello: And then we started to -- knock on doors. "Anyone see this boy?" … We worked all that day, we worked all that night. And then the following day I got home. And – I -- I was ready to break down myself.

Richard Schlesinger: Because?

Patrick Eanniello: Because I -- I saw my son.

Richard Schlesinger: And he was Etan's age?

Patrick Eanniello [emotional]: Uh-huh, yeah.

A command center was set up in the Patz's apartment.

Stan Patz|Etan's father [1979]: Both my wife and I continue to be confident that he is alive and we hope he's being cared for by someone who might want a child as adorable as he.

Julie Patz [1980]: The police did not know us. We had to be cleared of suspicion as well as many other people.

Etan's image was splashed on storefronts and in newspapers. Etan's father is a professional photographer and took many photos of his son. The pictures captured the public's heart—and captured Etan's spirit.

Julie Patz [1980]: He's just bubbling over with life and … He always saw the positive side when other people saw negative. He is just an incredible person.

Stan Patz [1980]: Our 6-year-old boy's a loving, trusting child. …We think an adult could have convinced him to come with him.

The police canvassed the neighborhood, talking to people on the street and interviewing workers at a corner store near the school bus stop.

Det. Bill Butler [1980]: The longer we've gone without any bad news, I think that's good.

Detective Bill Butler was Eanniello's partner.

Det. Bill Butler [1980]: We have leads, but we don't know where we're gonna end up on the leads that we have now.

Det. Bill Butler [1980]: When you go this long on something like this, you do, you feel like you're looking for your own son.

The search for Etan dragged on. Detective Butler, a father with six children, lived and breathed the case.

Richard Schlesinger: How did this case influence Bill Butler?

Patrick Eanniello: More than I could imagine. He was very, very tied into the case.

In 1986, Bill Butler took his own life. There was speculation Butler's frustration with this case may have been part of the reason why.

The search went on without Butler. Julie and Stan had two other children to protect: Etan's older sister and younger brother.

Julie Patz [1980]: We keep saying we try to lead normal lives, but in so many small ways, it's just totally impossible, I mean we have his belongings all over the house … And yet to put them away is saying to us and our children he's gone and not coming back.

Stan Patz [1980]: And if we are patient we'll get him back.

But their patience went unrewarded.

The Patz's did everything they could to keep their story in the news. And that helped other missing children.

In the 1980s, milk cartons showed Etan's face, and then, those of others. But Etan remained among the missing.

By 1998, a new detective was heading the Missing Persons Squad. Phil Mahony was drawn to the case by, of all things, a poem titled "The Missing Boy" by Sharon Olds -- about a mother and son looking at Etan's missing poster.

Phil Mahony: And -- I read that poem and I said, [snaps fingers] "That's it. …I wanna work on the Etan Patz case.

Phil Mahony: It was pretty much inactive and had been inactive for many years.

Richard Schlesinger: It was cold?

Phil Mahony: It was colder than cold … we had to find the reports and put them back together.

Mahony sorted through nearly two decades worth of work -- and some bizarre tips.

Phil Mahony: This tip about this cult in Westchester.

Richard Schlesinger: Did that source say that Etan was -- there, at that cult?

Phil Mahony: Yeah, that Etan was killed by that cult and dumped.

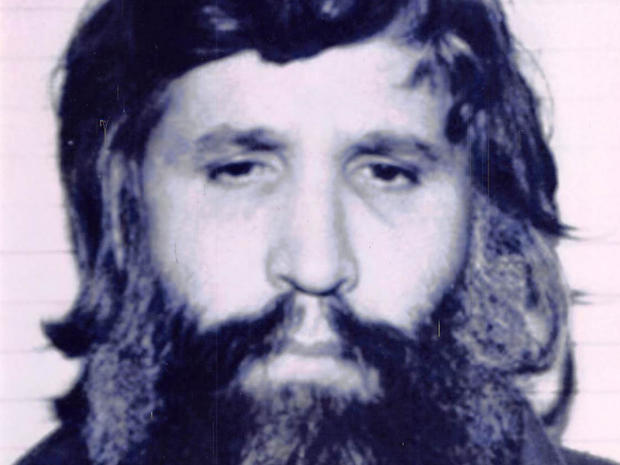

The leads led nowhere. But, there was someone who police were very interested in: Jose Ramos, the man who said he may have encountered a boy in Washington Square Park, not far from where the Patz's lived.

Richard Schlesinger: Did he say it was Etan Patz?

Phil Mahony He has said he was 90 percent sure it was Etan Patz.

A PERSON OF INTEREST?

In 1982, Jose Ramos was picked up by police for stealing some books from children. He was homeless, living in a drainage tunnel in New York City. Former Lieutenant Phil Mahony recalls Ramos had some disturbing photos.

Phil Mahony: He had a bunch of -- photos … of kids that looked like Etan Patz. …He was -- a shady character so he enjoyed lookin' at these photos.

So Ramos was questioned by investigators about the photos:

ASSISTANT D.A. FRANK CARROLL [evidence tape]: Did you ever hear of a kid named Etan Patz?

JOSE RAMOS: Yeah, that was in the papers in '79.

ADA FRANK CARROLL: What is about … that people say looks like Etan?

JOSE RAMOS: The smile, I think.

ADA FRANK CARROLL: How about the hair?

JOSE RAMOS: Maybe the hair. Not that much…

JOSE RAMOS: Susan used to take care of him, Susan Harrington.

Susan Harrington, Ramos's girlfriend, walked Etan to school during a bus strike shortly before Etan disappeared.

ADA FRANK CARROLL: Did you know where he lived?

JOSE RAMOS: In SoHo. Well, it was in the papers.

Investigators suspected Ramos was a pedophile who could have ties to Etan.

Phil Mahony: There was enough there, there was a lot there to draw attention to him certainly.

Etan often played in Washington Square Park -- a place Ramos was known to visit.

Phil Mahony: Jose Ramos … has said several times that on May 25, 1979 … he was here … when a young, small, sevenish … blond kid came up to him and started talkin' to him. And Jose Ramos said at that point he eventually took the kid back to his apartment.

Ramos told that story to Federal Prosecutor Stuart GraBois, who had been working the case since 1985. GraBois and the FBI had, through the years, tracked leads around the world. But they always came back to Ramos.

Stuart GraBois: In June 1988, Ramos was brought to my office … and proceeded to state … that he was 90 percent sure that the young boy he took that day, May 25,1979, was the same boy whose picture he saw both in the newspaper and on television -- that being Etan Patz.

Investigators learned Ramos had sexually molested children around the country.

Stuart GraBois: One of the things he did is travel around the United States in a converted school bus, giving out Matchbox cars and toys and baseball cards to children -- to young boys to entice them onto the bus.

GraBois wanted to prosecute Ramos even if it wasn't for the Etan Patz case. He succeeded in Pennsylvania. In 1990, Ramos pleaded guilty to molesting an 8-year old boy and was sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison.

Richard Schlesinger: You've got a known pedophile who says he was 90 percent sure he picked up Etan Patz, you know-- around the time he disappeared. Why didn't you just go," OK, case closed"?

Phil Mahony: Because we didn't have that corroborated evidence -- didn't have that one person who said, "Yeah, I saw him and Etan in Washington Square Park."

Investigators hunted for more evidence. In 2000, Mahony ordered a search of an apartment building Ramos lived in when Etan disappeared. Ramos had allegedly told a fellow inmate this is where he disposed of Etan's body.

Phil Mahony: When he was in jail, Jose Ramos said … that he put Etan into the furnace in the basement.

Richard Schlesinger: Of this building?

Phil Mahony: Of this building, and you know, burned up the body.

But like so many tips in the Etan Patz case, nothing came of it.

Phil Mahony: …there was just never that next thing to make you say, "Yup, that's it. Close the books, we got the guy."

Mahony felt they didn't have enough on Ramos to charge him with Etan's disappearance. Neither did the Manhattan D.A. at the time. But Stan Patz and Stuart GraBois were becoming more convinced Ramos was their man.

Stan Patz [2000]: I believe this man stalked my son. I believe he lured him back to his apartment. I think he used him like toilet paper and I think he threw him away [emotional].

Brian O'Dwyer is a prominent N.Y. attorney and started representing the Patz's. He was friends with Stuart GraBois, and in 2000 he approached GraBois with an idea.

Brian O'Dwyer: And I said, you know, you have an opportunity -- you may not have … thought about it, but of taking a civil case against Ramos.

It would be a wrongful death suit. O'Dwyer hoped Ramos would be subpoenaed and might say something incriminating to help bring a criminal case. But before the wrongful death case could proceed, O'Dwyer had to ask the Patz's to officially give up hope. They would have to ask a court to declare their son dead.

Brian O'Dwyer: It's one of the toughest things I've ever done in my practice.

And, on June 19, 2001, a judge declared that Etan Patz was officially dead.

Stan Patz [2000]: I used to have fantasies of a taxi cab -- pulling up in front, and Etan coming out of it. But -- that was a long time ago. I don't entertain those fantasies any more.

The Patz's attorney went to the Pennsylvania prison where Ramos was being held to interview the man he believed had killed Etan Patz.

Brian O'Dwyer: This was evil incarnate. …If I had met him on the street I would have been very scared.

Richard Schlesinger: And what did he say?

Brian O'Dwyer: He said that yes, indeed, he was on the street that day. And he picked up a little boy by the name of Jimmy.

This time, Ramos did not say Etan's name.

Richard Schlesinger: Were you convinced that Ramos was the guy?

Brian O'Dwyer: Absolutely.

Ramos would never answer more questions or testify in court, and the Patz's won the civil case against him.

Brian O'Dwyer [to reporters in 2001]: Once and for all we have a final declaration by a court of law that Jose Antonio Ramos caused the death of Etan Patz.

It was a victory, but it was not the end of the fight.

Brian O'Dwyer: The ultimate objective was to get a criminal prosecution

Richard Schlesinger: Did you think it was enough to prosecute him criminally?

Brian O'Dwyer: I did.

The Manhattan D.A. disagreed. He still would not charge Jose Ramos.

Brian O'Dwyer: He thought he couldn't prove it beyond a reasonable doubt.

Richard Schlesinger: Do you keep thinking about this case, or did you move on?

Brian O'Dwyer: No, I never moved on. Never moved on --

Richard Schlesinger: Really?

Brian O'Dwyer: No. Jose Antonio Ramos was in prison, unpunished, for what I believed was the death of Etan Patz.

But 33 years after Etan disappeared there was a tip -- and it could change everything in this case.

A TURNING POINT

Stan Patz [2000]: I – [sighs, emotional] I think about my son every day. He's -- gone, but I will never forget him.

As time passed for Stan and Julie Patz, Etan was, and is, frozen in time as a 6-year-old gone missing. They remained convinced that Jose Ramos, the pedophile who was behind bars in Pennsylvania, was responsible for Etan's death.

Stan Patz [2000]: I send him a -- poster twice a year. …and I write on the back, "What did you do to my little boy?"

From the time Etan disappeared in 1979 until 2009, one man held the position of Manhattan District Attorney: Robert Morgenthau. He never felt there was enough evidence to indict Ramos. But Morgenthau was retiring, and Cyrus Vance Jr. was running for the office.

Cyrus Vance Jr.: The Patz family reached out to me. …And Stan … asked me if I would -- look into the case.

And when Vance became Manhattan D.A. in 2010, he did look into it.

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: Cy Vance was like, "Listen, we'd like to re -- you know, fresh set of eyes, relook at it, go backwards, see what was missed."

Lt. Chris Zimmerman headed the Missing Persons Squad at the time, and part of the fresh look included another look at Jose Ramos.

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: We looked at the case for quite a while and I never was convinced … that there was proof beyond a reasonable doubt that Jose Ramos was Etan's killer.

And so the search for another suspect continued.

The FBI had been involved on and off since Etan's disappearance. In April 2012, investigators took another look at a handyman who used to work for the Patz's. Along with the NYPD, they started that dig. It was at the former site of the handyman's workshop.

FBI Agent [to reporters]: We're executing a search warrant regarding the disappearance of Etan Patz.

It was not far from where the Patz's still lived.

The dig went on for five days, as investigators sifted through subterranean spaces and decades-old dirt. It was starting to look like there might finally be some answers. In the end, nothing was found. The handyman was cleared. But this was not just another dead end – it was far from it. In fact, it led to the first major turning point in this case.

Det. Dave Ramirez: The call comes into our office, onto the phone right next to my desk.

It came from Jose Lopez, who called police after he watched news coverage of the dig. He said his brother-in-law might be involved in the case.

Detective Dave Ramirez helped lead the investigation.

Richard Schlesinger: Who was his brother-in-law?

Det. Dave Ramirez: Pedro Hernandez.

Richard Schlesinger: Had you ever heard the name Pedro Hernandez before?

Det. Dave Ramirez: No, sir, no.

Richard Schlesinger: What did he tell you about his brother-in-law?

Det. Dave Ramirez: That he had made -- statements to various people about him having done something really bad to a child in New York.

Pedro Hernandez worked as a stock boy at that corner store by the bus stop. He was 18 when Etan disappeared. And soon after, Hernandez left that job and moved home to New Jersey. Over the years, he had been divorced, remarried and had children. He worked on and off at menial jobs and had no criminal record. But he had told people about hurting an unnamed child.

Richard Schlesinger: So who had Hernandez spoken to?

Det. Dave Ramirez: There was a religious group, apparently there was a retreat that they had gone on … they all had – information … to the fact that Mr. Hernandez did something to this child.

Ramirez learned Hernandez also told his ex-wife and a friend, similar stories. Detective's notes from 1979 show police at the time knew Hernandez worked at the store, but it is unclear if he was ever questioned.

Richard Schlesinger: Why do you suppose he was not a suspect before?

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: I don't have the answer for it. I wasn't there. You know, I -- I never got clarity on that and I don't think he did either.

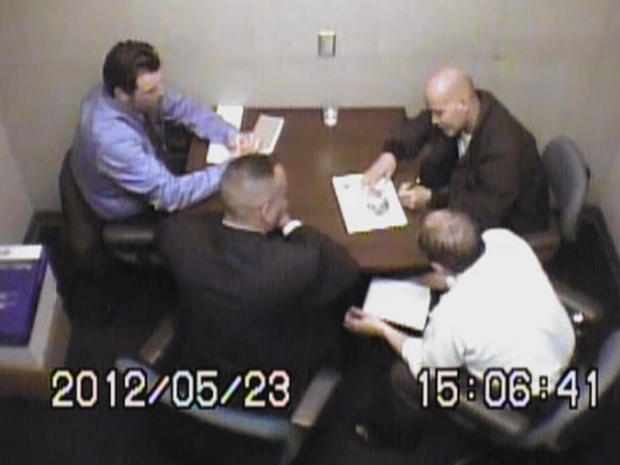

About two weeks after they learned about Hernandez, on May 23, 2012, police went to his New Jersey home to talk to him.

Det. Dave Ramirez: I had -- told him that we were investigating an old … missing persons case … in New York City. …At that point, he like, he lost all the color in his face.

Still, Hernandez readily agreed to go to the prosecutor's office in Camden, N.J. to be questioned.

Richard Schlesinger: Was it hard to get him talking?

Det. Dave Ramirez: No, no.

He talked for six hours without a lawyer or a recording of the conversation. During that time, he was shown a missing poster of Etan Patz. Later, the video camera was turned on and Hernandez told them about seeing a boy outside the store where he worked:

INVESTIGATOR: Can you start telling us again exactly what you just told us before, about what happened.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: He was waiting for the school bus.

INVESTIGATOR: Who was waiting for the school bus?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: The kid.

INVESTIGATOR: What's his name?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: Etan Patz.

These are the words that changed the course of one of America's most heartbreaking cold cases. Hernandez went on, telling police he offered Etan a soda:

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: And then I ask him -- I ask him to go to the, in the basement with me to get the soda.

It is hard to listen to his story:

SECOND INVESTIGATOR: And then what happened after that?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: And then I choke him … Yeah, when I choked him he went like this [puts his hands to his throat, then goes limp and drops his arms to his side].

INVESTIGATOR: What made you do this?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: I don't know.

INVESTIGATOR: You don't know?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: …It was something that it just happened.

He signs Etan's missing poster, writing: "I am sorry … and "choke him"

INVESTIGATOR: And you recognize this to be the boy that you choked that day?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: Yes.

After the confession, Hernandez showed investigators where he said it happened 33 years earlier. Lt. Zimmerman recorded the walk with his cellphone:

Richard Schlesinger: So Hernandez told you here that this was the basement entrance…

Det. Dave Ramirez: Yes.

Richard Schlesinger: So according to Hernandez, Etan was … that way from where we are.

Det. Dave Ramirez: Yes.

Richard Schlesinger: And he lured him in -- into the basement through this door.

Det. Dave Ramirez: Yes, sir.

Hernandez said he put him in a box after choking him.

Det. Dave Ramirez: Put him in a box.

Richard Schlesinger: And then put the box on his shoulder.

Det. Dave Ramirez: Carry the box up out here … At this point, I said "could you show us exactly the way you walked that day?" We crossed the street to the other side.

Richard Schlesinger: And how far down did he go?

Det. Dave Ramirez: And then he went down to the corner.

Hernandez showed them where he says he disposed of a box with Etan's body.

Police believe the box was picked up by garbage collectors. Hernandez was interviewed again hours after the SoHo walk, this time by a prosecutor in the Manhattan D.A.'s office:

PEDRO HERNANDEZ [to Asst. DA]: Then I choked him. And I tried to let go, but I just couldn't let him go.

He repeated the same story. And later that day, Pedro Hernandez was arrested.

Then-NYC Mayor Mike Bloomberg [to reporters]: We have a suspect in custody who has made a statement to the NYPD, implicating himself in the disappearance of Etan Patz, 33 years ago.

Cyrus Vance Jr: He had confessed to killing Etan Patz. It was a credible confession.

So says the prosecutor. But soon, questions were being asked about the six hours when Hernandez was questioned before the videotaping began.

Richard Schlesinger [to Vance]: Why weren't those first hours videotaped?

UNDER ARREST

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: It was a day or two shy of the 33rd anniversary. It was a day or two shy that we made the arrest.

Then-NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly [to reporters]: This evening the NYC police department is announcing the arrest of Pedro Hernandez…

Lt. Chris Zimmerman [to reporters]: Mr. Patz was taken aback, a little surprised and I would say overwhelmed.

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: You know, it had to sink in. You know, 30-something years, it had to sink in. …I can't imagine not having an answer for that many years.

For decades, Stan and Julie Patz believed another man was responsible for their son's disappearance in 1979.

Stan Patz [2000]: I believe this man stalked my son. …And I want him to admit it [emotional].

Now, someone was admitting it. But it was Pedro Hernandez.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ [to investigators]: He was waiting for the school bus. …then he went down the steps … when I choked him [puts his hands to his throat] he went like this [goes limp and drops arms to his side].

After Hernandez was arrested, he was thought to be a suicide risk and taken to Bellevue Hospital.

Harvey Fishbein | Attorney: I met him at the … prison ward.

Harvey Fishbein is Pedro Hernandez's court-appointed attorney.

Harvey Fishbein: …and I walked out of there and I said, "The man has an issue that needs to be addressed."

PEDRO HERNANDEZ [psychiatric exam video]: I hear voices sometimes, talking to me.

A defense psychiatrist diagnosed Hernandez with a personality disorder that can leave a person unable to differentiate between what's real and what's not.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ [psychiatric exam video]: I had, uh, visions.

Richard Schlesinger: Do you think Pedro Hernandez knows if he killed Etan Patz or not?

Harvey Fishbein: I – I think he knows he didn't. And that's the-

Richard Schlesinger: You think? Are you sure?

Harvey Fishbein: It's hard to look into someone's mind, which is one of the real problems we have here.

The diagnosis of mental illness would be a major part of Hernandez's defense. In January 2015, two- and-a-half years after his arrest, Hernandez went on trial for the murder of Etan Patz.

NEWS REPORT: Etan Patz's father walked silently past reporters in the courthouse ... finally hoping to see justice served nearly 36 years after his young son's disappearance.

At trial, the defense would argue that Hernandez's mental illness made him make up the whole story of murdering Etan, starting with seeing him by the bus stop.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ [to investigators]: He was waiting for the school bus.

Harvey Fishbein: Pedro says, "I saw him standing there."

Harvey Fishbein: Yet, no parent that was at the bus stop that morning who knew Etan, saw Etan that morning. …So the fact that Pedro said that he saw the child there when no one else did immediately raises questions as to did this actually happen or not?

Hernandez told investigators he tried to hide Etan's book bag in the store's basement.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ [to ADA] So I took the book bag and I threw it behind the freezer.

But Fishbein says the police would have searched that store and, if they did, should have found the bag or some other evidence.

Harvey Fishbein: That bag was never recovered.

The defense also argued that Hernandez has a low IQ and is susceptible to suggestions.

Harvey Fishbein: We -- argued to the jury that … He's unreliable because of his low intellect. …because of his psychiatric condition. And … 'cause the story in the end does not make sense.

But the prosecution experts interviewed Hernandez and concluded he is not mentally ill, and that the jury could believe his words.

Prosecutors had home videos showing Hernandez socializing like anyone else. And they pointed out that Hernandez never reported any mental illness on a driver's license renewal form he filled out.

Richard Schlesinger: Do you believe that he was competent to confess?

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: Absolutely. …I think there was ample evidence that Pedro Hernandez was not – fabricating – this -- homicide as the product of mental illness, but that he in fact was -- admitting to something that had tortured him … and he confessed.

But Fishbein wants the jury to wonder what happened during those six hours before the videotaping began.

INVESTIGATOR [to Hernandez]: Can you start telling us again exactly what you just told us before, about what happened?

Harvey Fishbein: There was an affirmative decision not to videotape what was going on. All it would've taken was the pushing of a button.

Richard Schlesinger: Why wasn't that taped?

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: I think it was not taped, because … there was no legal requirement that it be taped.

Richard Schlesinger: How do you know that they didn't feed him information? How do you know they didn't berate him?

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: The way you assure yourself is by talking to the witnesses who were there. … after speaking to those who were present and being informed of what happened, I did not doubt that there was anything but a fair handling of Mr. Hernandez and appropriate questioning of him.

Richard Schlesinger: Did you give him any information about the crime when you were talking to Mr. Hernandez?

Det. Dave Ramirez: No.

Richard Schlesinger: Did you try and influence him?

Det. Dave Ramirez: I wouldn't say. No.

Richard Schlesinger: This was all him just talking to you, volunteering this stuff?

Det. Dave Ramirez: Yes.

The defense argued police preyed on Hernandez's vulnerability and manipulated him to confess.

Harvey Fishbein: Pedro is a very religious person … One of the detectives … says, "Thank you, Pedro."

INVESTIGATOR [to Hernandez]: I can't begin to tell you how proud I am of you.

SECOND INVESTIGATOR [to Hernandez]: Right there is strength. That's the strength of the Lord.

Harvey Fishbein: "That's the strength of the Lord." …What's the strength of the Lord? That he said something that they said they needed in order to make people feel better, the family to resolve it?

Richard Schlesinger: But the police would counter and the prosecutors would counter that this guy confessed to so many people over the years that he corroborates his own words.

Harvey Fishbein: Well, they-- they would like to say that. I don't think that's accurate.

Richard Schlesinger: They do say that --

Harvey Fishbein: I know -- and I don't think that's accurate.

The prosecution called those church members, Hernandez's ex-wife, and his friend who all said Hernandez told them he did something bad to a young boy. But at the time, they never reported anything because they didn't know whether to believe him.

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: If it was one statement in isolation, that would be one thing. …There were a number of people to whom he unburdened himself.

But Fishbein told the jury those accounts varied and Hernandez may have been making them up to look tough. And he offered the jurors another suspect; the man many, including the Patz's, first thought killed Etan: Jose Ramos, the known pedophile whose girlfriend knew Etan.

Harvey Fishbein: I feel certain that if the District Attorney's Office tried Jose Ramos, he would be convicted.

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: The evidence against Pedro Hernandez was much stronger than it had ever been against Jose Ramos.

The prosecutors had one piece of evidence they considered critical. It was something Hernandez said when he showed police where he said he dumped Etan's body. He noticed there was a door where he didn't remember one.

Det. Dave Ramirez: And he says, "There wasn't a door there."

When they researched the building's history, prosecutors discovered Hernandez was right. The door was added after 1979.

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: That's a fact that was not known publicly… that we believed only the killer would know.

But the defense says Hernandez wasn't even sure which building it was.

DETECTIVE [to Hernandez]: Which one? Can you remember if it was this one?

Harvey Fishbein: He said … "I thought maybe this is it." And then he looks and he says, "No. This is it."

DETECTIVE: OK, this is the one, right?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: Yeah, I think so.

It was a lot for the jurors to sift through. The trial took nearly three months. And in April 2015, they began deliberating and deliberating … for 18 days.

THE TRIALS OF PEDRO HERNANDEZ

For 18 days, the jury considered Pedro Hernandez's confession to the murder of Etan Patz.

SECOND INVESTIGATOR: Then what happened after that?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: And then I choke him.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: Yeah, when I choked him, he went like this [hold hands to his throat, drops his arms to his sides and goes limp].

Adam Sirois was one of the jurors.

Adam Sirois | Juror: A big bone of contention was the mental health issue. …We debated that for days.

Adam Sirois: The other issue that was very sticky at first was the confession … Everyone felt very upset about not being able to see the entire interview.

The jurors disagreed on whether the confession could have been coerced. Twice, they told the judge they were at an impasse. And, the third time they reported they could not reach a verdict. On May 8, 2015, the judge declared a mistrial.

Stan Patz [to reporters]: Our long ordeal is not over.

Harvey Fishbein: When they said they were unable to reach a decision, we believed it was going to be 11-to-1 for acquittal.

It was 11 to 1 -- but not for acquittal. Only one juror voted not guilty; it was Adam Sirois.

SECOND INVESTIGATOR: Do you remember the date?

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: No.

PEDRO HERNANDEZ: No. …the date was… the 25th…

The juror found the confession hard to believe, not knowing what went on before the camera started rolling.

Richard Schlesinger: You know, it's very hard for people to wrap their minds around the idea that somebody would confess to murdering a child -- if he didn't actually do it?

Adam Sirois: Yeah. … And a lot of the jurors said that in -- in our deliberations. …But the whole reason why you don't just throw someone in jail when they confess is that there's a lot of people out there with mental illness that could confess to lots of crimes. And it doesn't mean they're all guilty.

But rest of the jurors believed Hernandez was guilty. Still, 11 out of 12 is not enough to convict. And Stan Patz was obviously disappointed.

Stan Patz [to reporters after mistrial]: This man did it. He said it. How many times does a man have to confess before someone believes him?

D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr.: Stan was -- was unequivocal in his support that the case should be retried. And so we did.

A year-and-a-half later, Pedro Hernandez went on trial again. The evidence and the issues were the same as the first trial. And, like the first trial, it was long -- more than three months. This trial also ended with a long deliberation -- nine days.

Richard Schlesinger: Did it start feeling like the first time to you?

Harvey Fishbein | Defense attorney: Nothing ever felt like that 18 days the first time. But yes. It was reminiscent of that and … we were just trying to understand what was going on. It's impossible to try to read a jury.

But unlike the first trial, this jury reached a verdict. Pedro Hernandez was convicted of killing Etan Patz 37 years after the first-grader left home and vanished.

- Pedro Hernandez gets at least 25 years in 1979 missing boy case

- "The Lost Boy:" Nearly four decades without a conclusion -- until now?

Stan Patz [to reporters]: The Patz family has waited a long time, but we have finally found some measure of justice for our wonderful little boy Etan. …I am truly relieved and I tell you, it is about time. It really is about time.

Pedro Hernandez was sentenced to 25 years-to-life.

Richard Schlesinger: Why do you think this case was so hard to solve? Why did it take so long?

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: My opinion. …I think people had great intentions. … I think people got focused on people like Ramos. I'm not criticizing anybody independently, 'cause it made a lotta sense. …He's an evil man. He's just not our evil man.

It's a feeling now shared by others who once were convinced Jose Ramos murdered Etan Patz before police found Pedro Hernandez.

Brian O'Dwyer: If I were on the jury, I would have come with the same verdict.

Richard Schlesinger: Do you still think of Etan Patz?

Brian O'Dwyer: I do.

Richard Schlesinger: What do you think about?

Brian O'Dwyer: It could have been my son.

That is the thought that still haunts so many involved in this case. Phil Mahony, long retired from the NYPD, is now an attorney and still thinks about Etan.

Phil Mahony | Former NYPD lieutenant: My kids are, like, 22, the youngest, and I still think about it when I'm -- when they're out of sight and out of mind.

Patrick Eanniello | Former NYPD detective: We were kinda hopin' that it would be like a movie ending where the -- the boy would eventually walk in the door. …But it didn't work out that way.

Richard Schlesinger [referring to Etan's missing poster]: I've noticed a couple of times you've looked down at this. Why do you – it still means something?

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: Yeah, this is, this is the poster we remember the most, I would say. This is -- the kids lookin' right at me. … I feel for the family. I'm a father myself, and so is Dave.

Richard Schlesinger: Case is solved, but --

Lt. Chris Zimmerman: Solved but I never gave them complete closure. I couldn't give 'em their son back. [Tears up, puts head down] …Would have loved to give them their son back.

Etan's remains have never been found.