Environmentalist Bill McKibben on national security implications of climate change

In this episode of Intelligence Matters, host Michael Morell interviews author and environmentalist Bill McKibben about the national security implications of climate change, including how current trends, if unchecked, could lead to future catastrophes. McKibben explains why taking certain actions immediately and for the next ten years is crucial in order to forestall mass migrations, crop shortages and deadly droughts. He shares his views on the troubling parallels between climate change and certain accelerating technologies like genetic modification.

HIGHLIGHTS:

- Climate and mass migrations: "We've seen big shifts in how water moves around the planet because warm air holds more water vapor than cold, and as a result, we see big increases in drought in dry areas and with it these massive and wicked wildfires. And then we see big increases in precipitation, downpour, flood in wet areas. And all those things are combining already to produce big human costs, including the early stages of what most people predict will be by far the biggest migrations in human history as people flee places that have simply become too hot or too salty or too flooded or too dry to allow them to go on living there. And I don't need to tell you what the national security, international security implications of that many people on the move will be."

- 2020 election stakes: "We're past the point where stopping climate change is on the menu. But if we don't do that, then, as you point out, we are already beginning to move past a series of tipping points that are irreversible. Nobody has a plan for freezing the Arctic now that it's melted. So 2030 is an important and almost literal deadline. And you know enough about politics and government to know that if you want something to happen in 2030, you'd better start in on it. I'm with those people who say that the election of 2020 in this country is probably going to be the most important one we ever had. And one of the reasons is, maybe the preeminent reason is, if we don't get it right very fast, our chances of getting it right slip by forever."

Download, rate and subscribe here: iTunes, Spotify and Stitcher.

Intelligence Matters: Bill McKibben

Producer: Olivia Gazis

MICHAEL MORELL: Bill, welcome to Intelligence Matters. It is very good to have you on the show.

BILL MCKIBBEN: It's a real pleasure to be with you.

MICHAEL MORELL: You know, I wanted to have you on since I read your most recent book over the holiday season in December. But unfortunately, COVID and some other things got in the way. So I'm so glad we were able to make this work.

I should tell our listeners that the book I'm talking about – Yes, the holiday season. It was a great time to read your book – I want to tell our folks that the book published last year is titled "Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?" And I want my listeners to know that a podcast on national security – what's a podcast on national security talking about this book for?

And it's my view that national security is about both threats to our nation and about threats to our people. And that's what I thought about as I turned every page of your book as I read it. So that's why I wanted to have you on. You discuss two important issues in your book. One is climate change. The other is is technology. I want to primarily focus on climate change, but I do want to ask you some questions about technology as well. So let me let me start, Bill, by asking: what led you to write the book?

BILL MCKIBBEN: Well, you know, I'd written the first book about climate change, a book called, "The End of Nature," back in, believe it or not, 1989. So I've followed this most absorbing of topics for a very long time – really, since it became a public topic. And I felt like we needed to get a sense of where we stood three decades later. And of course, the news is mostly bad. I mean, what were warnings in the late 1980s about what would happen if we didn't take this seriously, have by now become bulletins from the front line in a planet that's increasingly under siege from changes in the climate.

And I mean, as you were reading it over the holiday season, which seems a very long time ago, it's hard to remember now, but 2020 began with the spectacle of the continent of Australia half burning to the ground. We're far along in this story now.

MICHAEL MORELL: So what's the bill what's the overall theme of the book?

BILL MCKIBBEN: Well, I suppose if there's a theme, it's to let people understand both where we find ourselves, which is in a very difficult place, past the point where we can stop global warming, at the point where maybe we can still stop it short of cutting our civilisations off at the knees, but only if we move very quickly.

That was one point, but the other was to try and help people understand how we got to this point. And I think that there's a deep connection with the, well, with the move towards societies that worshipped markets, that devalued collective action and government action, that kind of world view that began in the Reagan era and the Thatcher era, the one that said that markets solve all problems.

I mean, look, this has not been this has not been a good year for that idea. What did the pandemic teach us along with climate change? It's that there are problems that can only be solved when we act together. Ronald Reagan used to -- his great laugh line in all his speeches was, "The nine scariest words in the English language are, 'I'm from the government and I'm here to help'" – ha, ha, ha. But really, the scariest words in the English language turn out to be, 'We've run out of ventilators; The hillside behind your house is on fire.'

MICHAEL MORELL: Yeah. So, Bill, you write in the book about something that you call 'leverage.' What is that? And why is that important?

BILL MCKIBBEN: We live at a moment when every mistake gets magnified. So, I mean, look, it was completely possible for human beings to screw up in all kinds of ways at other points in our history. But our numbers were smaller and our technology less all-encompassing so, you know, it didn't matter in quite the same way. There was nothing that the Holy Roman emperor could do that could change the P.H. of the oceans, that could alter the temperature of the atmosphere, that could melt the ice caps.

We have, between our numbers and our technological reach, the ability now to make changes that are on an unbelievable scale. And too much of that leverage also exists in too few hands. I mean, we know, I'm afraid, in our country that too many decisions get made by a tiny coterie of people who control an enormous amount of our wealth and hence our political power.

So in every way, we're at a period of over-leverage, it seems to me. And and really, we need to figure out how to back off some, which is a hard thing for humans to do, but not an impossible one.

You know, we actually have some emerging technologies that are different than the ones that we're used to. The engineers have dropped the price of a solar panel or a wind turbine 90 percent in the last decade. And that's really good because if we wanted to, we could move fast to deploy them. And they produce a lot less carbon than burning oil and gas. But they also, in another way, lower leverage, too.

I mean, look, you think a lot about national security. So you know how much unearned power [is] concentrated in the hands of people who just happen to control the small deposits of hydrocarbons on which we depend. I mean, that's why we pay attention to the Koch brothers. They're our biggest political players and also our biggest oil and gas barons. That's why we pay attention to the king of Saudi Arabia. It's not like he's thought up some interesting new idea about governance – they cut people's heads off with a sword, you know – but as long as they control this thing on which we depend, they have outsized power. But everybody has some sun and some wind, and moving in those directions will help rebalance us in lots of ways.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Bill, I want to dig down, if it's OK, a little bit into climate change. And I guess I want to start by asking you: when did we realize that we had a problem with greenhouse gases and then where are we today? And and how did we get here from that moment of discovering that we had a problem?

BILL MCKIBBEN: Good question and it lets us talk about all kinds of interesting history. You know, humans began changing the atmospheric chemistry about 300 years ago when we started burning coal on a large scale. And that's just been increasing ever since. It was in the late 19th century that the first person to alert us that really this might in real time cause real trouble – the great Swedish chemist, Svante Arrhenius, who won the Nobel for other work, managed to predict with with remarkable accuracy, since he didn't have computers to work with, about how much the temperature would increase.

And nobody paid that much attention to it for most of the 20th century because we didn't have computing power large enough to really work out where the danger lines lay. But in the 1980s, scientists really began to be able to tackle this problem. And it was in those years that we started to get the first announcements.

The most important moment came in 1988, when NASA scientist Jim Hansen testified before Congress that climate change was real and dangerous and underway. Now what we now know, thanks to great investigative reporting by many of your peers at the L.A. Times, Columbia Journalism School and elsewhere, what we now know is that the fossil fuel industry had known about this in that same time period in the 1980s. They had good scientists and their product was carbon. So they were studying it and coming up with the same conclusions.

We know, for instance, that Exxon scientists predicted with stunning accuracy what the temperature and the CO2 concentration would be in 2020. What they didn't do was tell the rest of us. They engaged in, well, in a massive project of disinformation across the industry, spending billions of dollars in order to cloud the picture. And so we've wasted 30 years in this completely pointless debate about whether or not climate change was, quote, "Real," unquote – a debate that both sides knew the answer to at the beginning. It's just one of them was willing to lie. And that lie turns out to be probably the most consequential lie in human history, because we won't get those 30 years back.

So where we stand now is that the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, which, before the industrial revolution was about 275 parts per million, is now well north of 415 parts per million. In fact, in last month it hit a new record, just about four hundred and eighteen parts per million.

That doesn't sound like an enormous change; we're measuring it in parts per million, but it means that the temperature of the earth has already gone up about one degree Celsius, 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit.

Again, that doesn't sound so enormous. I mean, if it was 60 degrees when you walked into your office in 62, when you walked out, you wouldn't notice that much difference. But that extra heat is enough to have put huge changes in motion. It's the heat equivalent of exploding a Hiroshima-sized bomb every couple of seconds on this planet. And it's been enough heat to, for instance, melt about half the sea ice in the summer Arctic. That extra carbon has dramatically changed the PH of the oceans.

We've seen big shifts in how water moves around the planet because warm air holds more water vapor than cold, and as a result, we see big increases in drought in dry areas and with it these massive and wicked wildfires. And then we see big increases in precipitation, downpour, flood in wet areas.

And all those things are combining already to produce big human costs, including the early stages of what most people predict will be by far the biggest migrations in human history as people flee places that have simply become too hot or too salty or too flooded or too dry to allow them to go on living there. And I don't need to tell you what the national security, international security implications of that many people on the move will be.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Bill, if we don't change course, if we don't change the current set of policies and current set of activities that we conduct as human beings, then where are we headed? How bad will this get? How dangerous will it get? Is it an existential threat to us as humans?

Bill MCKIBBEN: Short answer is, Yes, it is. And it's headed – I mean, it's not that difficult to kind of track where it's headed because it's almost a problem in math.

You know, at current rates of production of CO2 from burning coal and oil and gas, the earth passes fairly rapidly in the course of this century through a place where the temperature increase is two degrees Celsius – That's the target, the kind of red line that the world's governments tried to draw in Paris in 2015. We're on a trajectory now for a temperature increase someplace between three and four degrees Celsius.

And if we do that, I think the best estimate is that our odds of having civilizations anything like the ones that we know are very slim – just too much disruption, too much chaos. Already we can see, you know, places around the world where it's getting too hot for people to easily inhabit.

We've seen record temperatures, the highest reliably recorded temperatures ever on the planet in the last couple of years, with cities in the Middle East registering temperatures near 130 Fahrenheit. And, you know, heat index is as high as 160, 165 degrees Fahrenheit.

These are at the absolute limit of the human body's ability to cope. But the science is pretty clear that on current trajectories, that's what it's going to be like for days, weeks, even months across really large swaths of the planet: much of the Asian subcontinent, much of the North China plain, much of the Middle East. These are places where billions of people live.

MICHAEL MORELL: And what has to change, Bill, for us to get on a trajectory to fix this problem?

BILL MCKIBBEN: I mean, what has to change is, we have to stop burning coal and gas and oil. And we have to do it very quickly. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change set up by the UN, which is our main scientific body on these matters, issued a report in October 2018. It said that unless we had fundamentally transformed our energy systems by the year 2030, that our chances of meeting the targets set in Paris were essentially nil.

And they defined that fundamental transformation as cutting in half our emissions. So that's a huge job, really hard work. It's especially hard work because we have to squeeze it into 10 years instead of the 40 that we would have had if the fossil fuel industry hadn't wasted our time with its disinformation campaigns.

But that is not necessarily an impossible task. The dramatic decrease in the price of solar and wind power has changed the game in a lot of ways. And there are really important experts, people like Mark Jacobson at Stanford, who have published powerful guides as to how every state and almost every country on earth could meet those targets by 2030, 2035 at prices that are not only affordable, that are a huge bargain when you compare them with trying to pay for the damage that comes from climate change.

MICHAEL MORELL: So how much of what you just talked about – I think this is probably a short question. How much of what you just talked about is accepted science and how much of it is in dispute?

BILL MCKIBBEN: There really is no dispute within the scientific data about the basic trajectory of where we're going. And there really hasn't been for a long time. The science on climate change essentially became a matter of consensus by the mid 1990s.

I mean, there's immense amounts of work to be done about all the different, detailed parts of it, because it's an experiment that we've never carried out before on this planet, Or, in fact, nature's kind of carried it out a few times over the course of Earth's history: every four or five of these great mass-extinction events that have been triggered by changes in the chemistry of the atmosphere. But we weren't around to observe them. So we don't know exactly how it plays out. But the basic science of climate change is absolutely settled.

MICHAEL MORELL: And where does climate denial come from?

BILL MCKIBBEN: Climate denial comes from the fact that one of the richest industries on Earth would have to surrender its business model if we took climate change seriously. I mean, there's no mystery about where it comes from. It came from the really careful, calculated efforts of the fossil fuel industry to make sure that we didn't act.

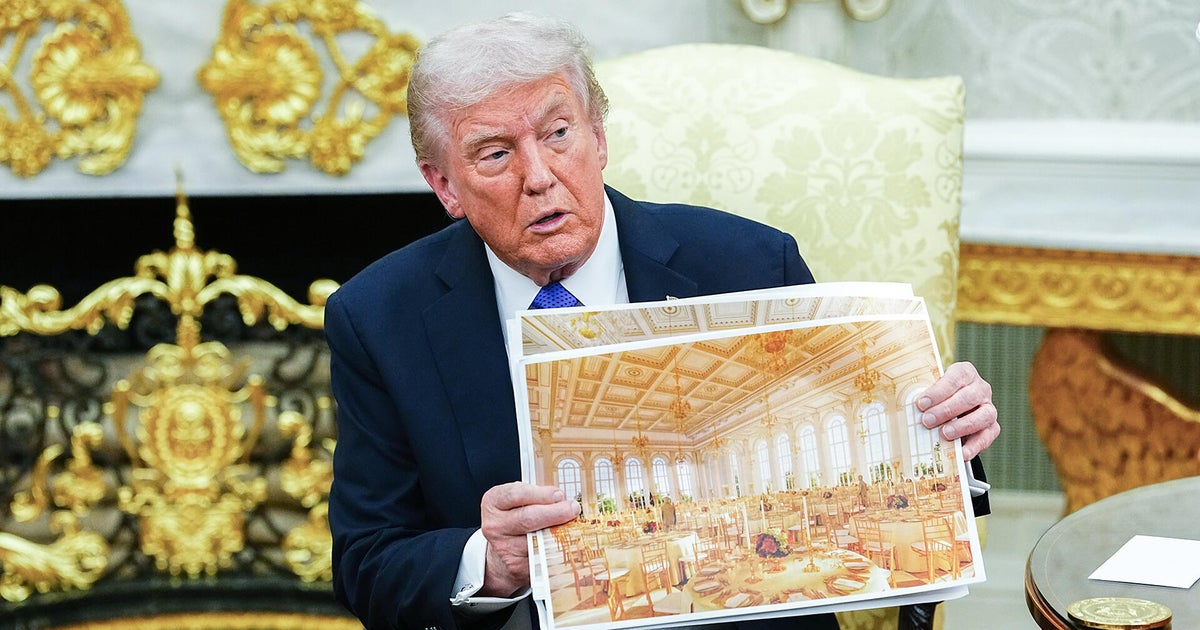

And as I say, we've now had great investigative reporting making that clear in every way. And, you know, the good news is that finally, after 30 years, that climate denial is wearing off. I mean, obviously it still infects people like Donald Trump. But it's hard to imagine that even among his supporters, there's many people who take him seriously as a source of scientific information.

For the rest of the world, even for the oil companies, now, at this point, they have no choice but to admit that that reality, in fact, is real. And now they're just engaged in a kind of ongoing effort to delay and postpone the inevitable.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Bill, I want to read a few quotes from your book that I found really powerful, and I just want to get you to react to them. So the first one is, "We've used more energy and resources during the last 35 years than in all of human history."

BILL MCKIBBEN: This is what I was trying to say about 'leverage' before, the kind of momentum of our situation. You know, I wrote the first book about climate change in 1989. Human beings have emitted more CO2 since that book came out than in all of human history before it. We've been powering pell-mell ahead, even in the face of the stiffest warnings from the scientific community.

MICHAEL MORELL; The second one, which you've which you've talked a little bit about already, is, "The rapid degradation of the planet's physical systems that was still theoretical when I wrote 'The End of Nature' is now underway."

BILL MCKIBBEN: Yeah and of course it's just painful to look around every day and see the examples of it.

I mean, it's appearing that 2020 will be either the first or second hottest year on record, which is really astonishing because there's no El Nino underway – that change in the Pacific Ocean temperature that usually is required to have a record temperature year.

But now things have just gotten so hot that we look, say, at Siberia, where temperatures through the whole spring and early summer have been 20, 30 degrees Fahrenheit above what they should be. The temperature was above 100 degrees north of the Arctic Circle last month. And now there's enormous wildfires as the inevitable result of that kind of heat and the dryness that comes with it.

You know, something like this is going on around the world every day. Our attention has been transfixed a little by the pandemic so that we're not paying perhaps as much attention. But, you know, we're having worldwide outbreaks of locusts at the moment, triggered by changes in weather patterns and that are chewing up a huge amount of the world's food resources. Those sort of things are are, I'm afraid, very much what the future looks like.

MICHAEL MORELL: So the third quote, which you've already touched on a little bit as well, is, "The habitable planet has literally begun to shrink; a novel development that will be the great story of our century."

BILL MCKIBBEN: Yeah, look around. I mean, one of the effects of the rise in sea level, which is that people are beginning to abandon coastal areas, retreat away from the shore, because as sea level rises and as storms get more ferocious, that land is becoming less and less and less defensible.

That will accelerate as the decades wear on. And it's very hard to imagine scenarios where we at this point manage to make it possible for cities like Miami to sustain themselves in anything like their current form.

And of course, that's true all over the world in spades, because many places around the world where the sea is rising have no no resources to build walls and seawalls and things on the necessary scale.

We also see people having to leave places because drought and desertification have just made it impossible to raise crops or to pasture animals. And so they're on the move and already on the move in fairly large numbers. Those numbers will just keep growing. The UN estimate for climate refugees in the course of this century is as high as a billion people.

MICHAEL MORELL: And then the next one really, really caught my attention, got to me, actually. "We are far more rapidly than ever before in Earth's history, filling the atmosphere with a precise mix of gases that triggered the five great mass extinctions."

BILL MCKIBBEN: In the past we've had these episodes of mass extinctions because of episodes of extraordinary volcanism. You know, a thousand years – or more, millennia – of huge volcanic activity across vast areas in Siberia, in one case, India in another.

What's amazing is that it turns out that, you know, you can do the work of thousands of volcanoes with a fleet of cars with V8 engines, with, a fleet of power plants. We've dug up and burned so much coal and gas and oil in the last couple of centuries that we've become a kind of out of control volcano ourselves, and CO2 levels in the atmosphere are rising faster than we've ever been able to see them rise anywhere in the historical record.

MICHAEL MORELL: And then and then the last quote, Bill, is "The particular politics of one country, for one 50-year period, will have rewritten the geological history of the Earth."

BILL MCKIBBEN: Yes, this is the decision in, say, the Reagan years that we were going to go in this kind of, laissez-faire, deregulated approach to government allowed us to back away from taking action on climate change. And we have encouraged, through a series of international mechanisms like the WTO, most of the other countries in the world to take more or less the same approach to things.

And so in this most crucial of periods when we were finding out about climate change and when the temperature was beginning to shift was precisely the moment when we rendered ourselves least able to deal with it. We kind of unequipped ourselves.

MICHAEL MORELL: So just one more question on climate change, Bill and I don't know exactly how to ask it. But when will it be too late? When will inaction lead to a cascading set of consequences that it doesn't matter what we do at that point – is there such a time?

BILL MCKIBBEN: And I think the best way to think about it is to take this concept of leverage and kind of turn it around.

There's been a lot of negative leverage that's gotten us in the situation where we are. I think the science really indicates that the next 10 years is our period of maximum leverage to get things right, that the changes we make then – if we're able to move very, very quickly to renewable energy over that period, that will begin to slow and blunt the rise in temperature. And if that happens, then we can avert some of the worst.

Not all of it. We're past the point where stopping climate change is on the menu. But if we don't do that, then, as you point out, we are already beginning to move past a series of tipping points that are irreversible. Nobody has a plan for freezing the Arctic now that it's melted. So 2030 is an important and almost literal deadline.

And you know enough about politics and government to know that if you want something to happen in 2030, you'd better start in on it. I'm with those people who say that the election of 2020 in this country is probably going to be the most important one we ever had. And one of the reasons is, maybe the preeminent reason is, if we don't get it right very fast, our chances of getting it right slip by forever.

MICHAEL MORELL: Bill let's switch gears and kind of talk about technology – walk us through your concerns.

BILL MCKIBBEN: I'm interested as you can tell in these questions of leverage and scale, and I have a feeling that we're now seeing the emergence of new trends that are sort of where climate change was 30 years ago. That is, visible as a threat, but we're not doing anything about it. And I hope we will examine it and think about it more closely this time before it gets out of control.

I'm talking about advanced artificial intelligence, the rise of human genetic engineering, these other technologies that I think are on a scale that makes it very difficult to imagine the kind of human future. And much of the book is about this question of what it means to be human.

MICHAEL MORELL: Any particular technology that concerns you?

BILL MCKIBBEN: As I write in the book, a good deal, I think that the prospect of human genetic engineering, in particular manipulating fetuses in embryo to produce some set of desired characteristics is a really dangerous step to be taking, and an unnecessary one, since we don't need to do it to deal with disease or defect. We would do it, if we did, in an effort to improve and enhance children. And I think that's a big mistake. I think humans as we know them, are fairly remarkable creatures and that we have all the gifts that we need, if we were to employ them, to build the kind of working world. And that's what we should be paying attention to.

MICHAEL MORELL: So it's easy – well, it's not easy, but it's it's easy to comprehend how bad the situation could be if we don't get climate under control. How bad could the situation get with the concept of genetic engineering?

BILL MCKIBBEN: I think that the concepts of human genetic engineering and artificial intelligence threaten – not apocalypse in the same way that climate change does – but threaten us with a future in which humans as humans, if that's important to you, lose much of our meaning and purchase on the planet.

It's still a philosophical discussion in a sense, because these technologies aren't quite ripe. But as the book points out, these are you know – if the oil barons were determined to hang on to one view of the future, this is another view that the barons of Silicon Valley are determined to hang onto. And they have an enormous amount of leverage and power in our political system. So the rest of us better take seriously the prospect of what's coming.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Bill, when I finished the book, I had two very different and seemingly contradictory ideas in my head. One was that we're doomed, and the other is that there's hope. Can you react to that?

BILL MCKIBBEN: The book is about the ways that we fight back. I've spent my last couple of decades really as a volunteer organizer in the climate fight. And we've tried our best to stand up against the oil industry and weaken its political power so we can make rational change. And I got to say, there are signs that that finally is working. Just in the last few weeks, we've seen plans abandoned for some of the massive pipeline projects that we've been fighting, the fossil fuel divestment effort that's now reached 14 trillion dollars' worth of endowments and portfolios that announced they don't want anything to do with hydrocarbons. That's become a huge weapon in the fight against the power of these companies.

And it's all because of people's mobilization. When people mobilize and fight, then we have a chance even against the enormous odds that our unequal society has produced for us. And so I hope we keep doing much, much more of that, Michael.

MICHAEL MORELL: The book is "Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?" The author is Bill McKibben. Bill, thanks so much for joining us.

BILL MCKIBBEN: Thank you.